In the voluminous discussion on the budget for fiscal year 2021-22 (FY22), to which I also contributed, there were hardly any references to Local Government finances (“Budget FY22: Meeting the Revenue Challenge” co-authored with Ramendra Basak, June 23, and “Expenditure Allocation and Effectiveness of the Budget,” June 29, both published in the Financial Express). That was not because Bangladesh’s local government finances are discussed on other days or in the areas they govern. Rather, they are rarely discussed because local governments are financially inconsequential, even though they will be highly consequential for Bangladesh’s development.

In the voluminous discussion on the budget for fiscal year 2021-22 (FY22), to which I also contributed, there were hardly any references to Local Government finances (“Budget FY22: Meeting the Revenue Challenge” co-authored with Ramendra Basak, June 23, and “Expenditure Allocation and Effectiveness of the Budget,” June 29, both published in the Financial Express). That was not because Bangladesh’s local government finances are discussed on other days or in the areas they govern. Rather, they are rarely discussed because local governments are financially inconsequential, even though they will be highly consequential for Bangladesh’s development.

This omission partly reflects the concern with responding to the Covid-19 pandemic. It is also true this pandemic has revealed the deplorable state of healthcare in the country outside the big cities. Further, the pandemic has shown the importance and, often, the absence of strong local governments that could mobilise communities to fight against it.

DE JURE DECENTRALSED; DE FACTO HIGHLY CENTRALISED: In law, de jure, local governments in Bangladesh have a firm constitutional basis. Chapter 3 of the Constitution states: ‘Local government in every administrative unit of the republic shall be entrusted to bodies, composed of persons elected in accordance with law’ (Article 59) and ‘Parliament shall, by law, confer powers on the local government bodies to impose taxes for local purposes, to prepare their budgets and to maintain funds’ (Article 60). Over the years, several legislations have upheld the constitutional articles: the Hill District Local Government Parishad Act (1989), the Zila Parishad Act (2003), the Local Government (Municipality) Act (2009), Local Government (Union Parishad) Act (2009), Local Government (Upazila Parishad) Act (1998) and Amendment (2009) and the Local Government (City Corporation) Act 2009.

Based on these acts, a local government structure of 61 District and three Hill Parishads (Councils), 12 city corporations, 329 municipalities, 491 Upazila Parishads (Councils), and 4573 Union councils operate. Under these legislations, de jure these governments can levy holding taxes, service charges, and oversee public health services, education, public libraries, parks, and critical infrastructures such as water and sanitation, drainage, waste management, local roads, and minor irrigation schemes.

In practice, Bangladesh is one of the most centralised countries in the world. Although Bangladesh is the 8th most populous country and has the 31st largest economy globally, the government spends more than 90 percent of all government expenditures centrally. The nearly 900 other city, municipal, and Upazila governments, including Dhaka, get less than 10 per cent of the national budget for their use.

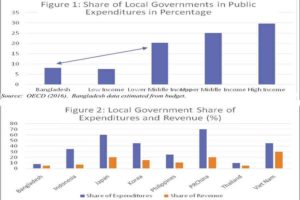

DECENTRALISATION AND DEVELOPMENT: Across the globe, as countries develop, decentralisation and the share of local government expenditures increase, as Figure-1 below shows. Local governments in high-income countries account for 30 percent of all public spending on average. In the lower-middle-income group, local governments’ share is 20 per cent.

Local governments’ share in overall government expenditures has averaged only about seven per cent in the recent years, nearly three times below its group average.

Neighbouring East Asia’s experience with decentralisation provides the most thought-provoking experience for Bangladesh for a few reasons. First, it has been the world’s fastest-growing region for the past 50 years, providing valuable lessons for other countries. Second, its experiences may have particular relevance for Bangladesh as some of its larger countries and Bangladesh share features. Several countries, and large parts of China, are densely populated tropical regions, where agriculture has thrived based on small-holder farms. Bangladesh has also followed East Asia to become an export-oriented manufacturing power generating rapid growth and structural changes.

The vast literature on the lessons of East Asian economies highlights the region’s outward-oriented and export-led growth, regional integration, foreign direct investment, prudent macroeconomic management that kept inflation low and exchange rates competitive, high rates of savings, and investment in infrastructure, health, and education. These factors enabled them to effectively use their demographic dividend, with high female labor force participation.

Omitted, however, in these accounts is that the East-Asian economies are among the most decentralised in the world and the critical role they played in their development. Subnational governments in East Asian countries had a significant and sometimes major share in public expenditures. As Figure-2 shows, sub-national governments in China, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan spend between 40 to 70 per cent of all government expenditures (the taller bars on the left).

In China and Vietnam, provincial, prefecture, and county governments have the principal responsibility and budgets for agriculture, forestry, irrigation, fisheries, power, water, employment, education, and health. They spend more than 80 per cent of expenditures on health and education and about 70 per cent of all public investment expenditures.

HOW DECENTRALISATION HELPS DEVELOPMENT: What role did decentralisation play in East Asian development? Elsewhere (Policy Insights, January 2019), I have discussed, at length, five different channels through decentralisation-boosted growth in East Asia. First, local governments and the people “owned,” and their welfare was closely tied to the local economy. These governments had the incentives, local knowledge, and the authority to generate their area’s development. Second, these incentives led to intense competition among local governments to develop faster. Third, mostly on their initiative and sometimes surreptitiously, they experimented with policy reforms later adopted by other local governments and nationally. Fourth, local governments helped identify and train leaders. Fifth, they supported high-quality urban development, essential for sustaining growth and structural change.

These lessons apply to Bangladesh. Let us discuss two examples. As just noted, high-quality urban development that provides good public services and a hospitable environment to attract investment and create jobs is critical for long-term growth. My research suggests that this process is stalling in Bangladesh. Due to the excessive concentration of economic activity and political power in Dhaka, the 341 city corporations and municipalities are denied funds and authority to promote robust urban development. That, in turn, deprives them of private investment and lowers the country’s long-term growth prospects.

Good urban development will need well-performing municipal governments to carry out planning, implementation, and monitoring activities. Effective coordination of these activities and public services will be critical. These activities will require detailed knowledge of how the city is performing and the issues confronting its development. Urban governments’ role is to solve market coordination failures and, to use economic jargon, “principal-agent” problems. It should be readily apparent that such direction cannot be provided from a distance by centralised governments. Thirty-two government ministries headquartered in Dhaka cannot coordinate the activities needed to develop Chandpur, Chittagong, or even Dhaka.

The failure to provide quality education – a necessary condition for development — is another example of a public service that needs local leadership. Although access to school education has expanded enormously, in the 2017 National Student Assessment of Class 5 students, only 12 per cent had grade-level competency in Bengali and 17 percent in Mathematics. One reason for this is schoolteachers are not accountable to students’ parents and the local community. The government’s policy to use Monthly Payment Orders to pay teachers directly in secondary schools illustrates this vividly. When teachers start receiving their salaries from the central government instead of through the local school body, their accountability and performance decline. What is true for education also applies to most other public services.

HOW SHOULD BANGLADESH PROCEED: First, it needs to decide on the leading tier of local governments. Our experience with Upazila governments and lessons of East Asia argue against decentralising to overly small governments. Small governments have an inadequate economic scale and revenue base, insufficient technical capacity; they increase fragmentation and coordination problems. We should, thus, consider making our 64 districts the main hub of local governments instead of the current focus on Upazila governments. Upazila and Union council governments should continue as lower-tier governments.

If implemented, our 64 district governments with significant authority over administration and budgets would be like the 63 provinces in Vietnam. Thus, we could also consider declaring our districts to be provinces. One political advantage of such an arrangement would be that this big hub of local government will not have one but several members in Parliament. That would help avoid the one-to-one confrontation that often takes place now between a single member of Parliament and the Upazila government because their constituencies closely overlap.

This approach will require a change in local government strategy. At present, districts are the weakest part of the local government structure. The functional assignments of the District Councils are unclear and residual: i.e., often defined to be those not assigned to the Upazilas or central government. Consequently, resource flows to districts are limited. It is no wonder that district government elections have been delayed and ignored.

Second, while the Constitution and different legislations have put in place local governments, new legal frameworks will be needed to mandate the following: (i) the distribution of functional assignments among the central and local governments; (ii) administrative authority of local governments over a larger and more qualified body of officials; and (iii) the revenue and expenditure responsibilities, and a system of formula-based financial transfers from central governments.

We will need two commissions. First, a Finance Commission that periodically recommends a formula-based allocation of fiscal resources vertically among the different tiers of government and horizontally across districts. This allocation formula should aim to provide both block grants to local governments based on population and other factors and conditional and matching grants to encourage local governments to help achieve national development goals: e.g., secondary education for girls. This commission should also allocate tax bases among the different tiers. A critical task will be to strengthen property and land tax bases for local governments.

Because not everything can be done at once, we will need a sequence of actions. Ideally, accountable local governments should depend significantly on their “own” revenues. In practice, achieving that will be a lengthy and challenging task. While work on increasing local revenue mobilisation should start, the focus should be to follow the East Asian model of “provision decentralising” or “expenditure decentralisation.” In effect, increasing local governments’ budgets for providing public services through fiscal transfers. This will require providing dedicated support to local governments with financial management expertise in budgeting, procurement, accounting, and auditing.

A second Administrative Commission should focus on increasing administrative capacity in local governments. A reasonably qualified local government civil service cadre accountable to the local authorities can be set up. To encourage superior performance, the upper echelons of this cadre should also have an opportunity to join the national civil service if their performance merits it. Local governments, however, will need to have authority – jointly with the central government – over the national cadre staff assigned to them. Such authority should include a voice on their performance evaluation, appointments, and tenure.

Finally, we will need a robust, transparent system for monitoring, evaluating, and ranking local government performance from the outset. Upper-tier agencies, but ideally independent, such as the CAG’s office, can carry out this work. Importantly, regional and national civil society groups and researchers should be encouraged to carry out these monitoring tasks in parallel.

All these tasks are complex and likely to be contentious. But we will have our own as well as international experience to guide us. It will be essential to encourage good research on these matters. It will also be important that the Commissions have widely respected and technically able members drawn from various parts of government and society. The Commissions should consider and encourage experimenting with decentralisation designs in different regions of the country.

Undoubtedly, a complex, challenging agenda lies ahead. It may be worth remembering the ancient Chinese saying that a thousand-mile journey starts with a single step. If Bangladesh wants to achieve upper-middle-income status by 2031 and meet the worthy Sustainable Development Goals, local communities and governments must be mobilised. The Covid-19 experience has only highlighted the importance of doing so. Let us remember that in working towards this goal, we will be working to realize the dream of the father of the nation.

Dr Ahmad Ahsan is Director, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh, and was previously a Dhaka University faculty member and a World Bank economist. The column draws on “Can Bangladesh Develop Without Decentralising? – How Decentralisation helped East Asia’s Development” Policy Insights, Policy Research Institute Quarterly, January 2019.