Introduction and Global Outlook

Doors Open for Deep Economic Reforms

The tectonic shifts that came within the political landscape in July-August has changed the course of Bangladesh history. The Monsoon Revolution, as it has come to be known, will have a place in the annals of history, at least for two reasons: first, a youth-driven movement toppled a government with absolute hold on power for over 15 years; second, the benign but firm stance of the Bangladesh army was unique and rare in the history of developing regions like Asia, Africa, and Latin America, where the military is known to seize power and take control of government, one way or the other. Not so in Bangladesh this time around.

The Interim Government, an entirely civilian construct, that was sworn in August is laser focused on change in the political and economic arena. A change of direction is called for in the financial sector, in macroeconomic management, in fostering economic integration with the global economy and attracting foreign investment. Although it was a political upheaval it also set off a momentum for long-delayed reforms in the economic sphere. A revolution, youth-driven as it was, presents opportunities that must not go waste. The doors for deep economic reforms are now open.

The Interim Government, an entirely civilian construct, that was sworn in August is laser focused on change in the political and economic arena. A change of direction is called for in the financial sector, in macroeconomic management, in fostering economic integration with the global economy and attracting foreign investment. Although it was a political upheaval it also set off a momentum for long-delayed reforms in the economic sphere. A revolution, youth-driven as it was, presents opportunities that must not go waste. The doors for deep economic reforms are now open.

After a tumultuous year of challenging internal and external imbalances, in 2024 the Bangladesh economy faced political turbulence that caused temporary setbacks to the key drivers of the economy. The critical message for policymakers and economic analysts of the Bangladesh scene is that political coalitions that fail to commit to good governance and democratic deepening often ends with economic disruptions and violent uncertainties, the severity of which can be judged only after a lapse of time. That is how the Bangladesh economy today is spanning out. The redeeming feature of this historic transformation is that the key drivers of the Bangladesh economy – readymade garment (RMG) industry, remittance inflows, agricultural production, GO-NGO partnership, and multilateral aid – all remain on course with minor hindrances. Economic stabilization has remained the central element of all economic and policy deliberations in FY24. For the past two and a half years, conspicuous macroeconomic challenges have complicated economic management for policymakers. The four key pillars of economic performance – growth, inflation, exchange rate and foreign reserves – have all experienced volatility and unfavorable trends fueling growing calls for adopting a policy and reform framework that supports broad economic stabilization and create conducive conditions for lasting resurgence in the economy.

Of course, these uncertainties, volatilities and growing questions concerning the management of the overall economy in FY22/23 stands in contrast to the relative macroeconomic stability and the admirable economic performance that Bangladesh has enjoyed for more than two and half decades, which defied the melancholy prophesies from skeptical development pundits. This also makes it essential that the Interim Government, which assumed office in the aftermath of the July-August Revolution, articulates a pragmatic forward looking strategy that not only ensures and supports economic stabilization but creates key capacities that empowers our economy to navigate an increasingly fragmented, volatile and sensitive economic order. So far, ‘reform’ has emerged as the buzz word within public discourse – and the Interim Government has expressed a stern commitment to give leadership to a broad range of much needed and desired economic and political reforms, encapsulated in the 3Rs: reset, reform, restart.

Yet, to identify how exactly Bangladesh should craft its economic strategy and understand how the economy has fared in FY2024, we need to explore the genesis of the current macroeconomic impediments. Furthermore, while the outbreak of Covid-19 in FY20 and the Russo-Ukraine war in FY22 did trigger the growing inflationary pressure and the depletion of forex reserves resulting from pent-up demand, critical supply chain disruptions and rising energy prices, the prevalent macroeconomic management in FY22/23 did not help either. More specifically, the influence of politically connected economic oligarchs on Bangladesh Bank paralyzed the monetary policy response, when there was an urgent necessity to break out of the 6-9% interest rate band to contain inflation and halt forex reserve depletion. This weakened the management of the growing inflationary pressure from mid-2022. The paralyzed monetary policy response also influenced our economic decision-makers to become excessively reliant on import compression and exchange rate depreciation to stabilize the Balance of Payments, which later triggered apparently strong negative outflow from the financial account – further depleting forex reserves in FY23, as private sector borrowers from the international market wanted to avoid the additional burden of a weaker currency on their corporate debt.

The results were severe macroeconomic instability characterized by a sharp depreciation of Taka, loss of foreign exchange reserves in the amount of $24 billion, downgrading of Bangladesh’s credit rating by the major rating agencies, a large and growing financial account deficit, and a persistently high domestic inflation.

Nonetheless, the economic policy response started improving in FY24-25 as the growing calls for adopting a market-based exchange rate and contractionary monetary policy framework to stabilize foreign reserves and tame the inflationary pressure gained increasing traction with policymakers. This was reflected in the upward adjustments of the policy rate of Bangladesh Bank, and the abandoning of the 6-9% interest rate band, and later – the treasury bill-referenced SMART framework – and then the eventual adoption of a market-based framework for interest rate management. On the exchange rate front, Bangladesh Bank under recommendations from the IMF adopted the crawling peg exchange rate framework, which is a flexible exchange rate regime that helps restore equilibrium in the Balance of Payments (BOP).

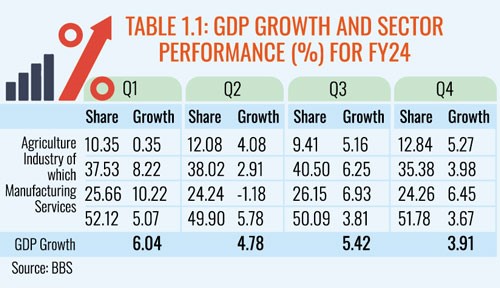

Collectively, these measures have aided the stabilization process of macroeconomic indicators, even though inflation remains stubbornly high – and the political uncertainties associated with the national election in January 2024 and the tightened monetary policy stance did slow down economic growth in Q2-Q4, FY24 through its’ unfavorable but expected implications for the industrial sector (See: Table 1.1). FY24 ended with a moderate GDP growth of 5.0 per cent. Yet, in the aftermath of the July Revolution, the commendable commitment of the Interim Government to much needed economic reforms, especially in the ailing banking sector, have raised fresh expectations concerning the prospects of the domestic economy, which has already benefited from the robust fundamentals of RMG export and the remittance sector. Moreover, if the monetary and fiscal sectors, and the trade policy regime receive the much-needed reforms (discussed in details in the last section) that can amplify their respective performance and help harness an in-built capacity to navigate the growing global economic turbulence, then FY25 can become a critical juncture that can mirror the attainments of the post FY92 liberalization era that placed Bangladesh on a formidable growth trajectory – experienced until 2023.

Global economic outlook and rising

economic fragmentation

Now that the US elections are over and Donald Trump is the President-elect, world leaders must brace themselves for the coming storm. Not only can we expect radical changes in the US economy and polity, the world can prepare itself for more cracks in the global trade order what with the looming across-the-board tariffs on all imports and higher tariffs on Chinese imports that Mr. Trump promised during his election campaign. If Donald Trump gets his way, we have seen nothing yet of the intensity of fragmented globalization that has crept into the global scene. Re-shoring, industrial policy, and trade wars will no doubt be intensified. Donald Trump has won a formidable mandate by promising increased economic nationalism through the imposition of enhanced trade protection and renewed commitment to industrial policies under the clever guise of supporting strategic autonomy and putting America First. Bangladesh economy can hardly be immune to this evolving global order.

Now that the US elections are over and Donald Trump is the President-elect, world leaders must brace themselves for the coming storm. Not only can we expect radical changes in the US economy and polity, the world can prepare itself for more cracks in the global trade order what with the looming across-the-board tariffs on all imports and higher tariffs on Chinese imports that Mr. Trump promised during his election campaign. If Donald Trump gets his way, we have seen nothing yet of the intensity of fragmented globalization that has crept into the global scene. Re-shoring, industrial policy, and trade wars will no doubt be intensified. Donald Trump has won a formidable mandate by promising increased economic nationalism through the imposition of enhanced trade protection and renewed commitment to industrial policies under the clever guise of supporting strategic autonomy and putting America First. Bangladesh economy can hardly be immune to this evolving global order.

One of the essential inferences or extrapolations that any expert or concerned analyst can draw from the economic turbulences experienced in FY22/23 is the intricate relationship that Bangladeshi economy has developed with the global economy, which not only makes the domestic economy vulnerable to global political and economic shocks through established trade and financial linkages but also creates a scope for the domestic economy to experience a buyout recovery when global economic conditions improve. This makes IMF’s recent assessment of the global economic outlook critical for policymakers as it underscores key improvements that should make local policymakers and economic actors cautiously optimistic.

One of the essential inferences or extrapolations that any expert or concerned analyst can draw from the economic turbulences experienced in FY22/23 is the intricate relationship that Bangladeshi economy has developed with the global economy, which not only makes the domestic economy vulnerable to global political and economic shocks through established trade and financial linkages but also creates a scope for the domestic economy to experience a buyout recovery when global economic conditions improve. This makes IMF’s recent assessment of the global economic outlook critical for policymakers as it underscores key improvements that should make local policymakers and economic actors cautiously optimistic.

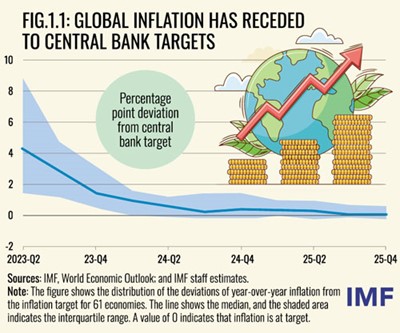

First: there is now a growing recognition that the worldwide battle against inflation has largely been won (…. but not in Bangladesh yet). After peaking at 9.4 percent year over year in the third quarter of 2022, headline inflation rates are now projected to reach 3.5 percent by the end of 2025 (See: Fig. 1.1), below the average level of 3.6 percent between 2000 and 2019. This has motivated key central banks, such as the FED in the United States and ECB in the European Union, to announce multiple cuts in their respective interest rates in 2024, which is likely to reduce pressure on the exchange rate of developing countries (like Bangladesh) against the US dollar- easing our own management of the inflationary pressure by mitigating the problem of imported inflation. Second: given global growth is likely to remain steady at 3.2% – while growth in advanced economies is expected to remain steady at 1.8%, it should aid the resurgence of our exports and remittances. Besides, what appears heartening to note is that the projected rate of trade growth for 2025 is 3.4%, which is expected to mildly outperform world output growth in 2024 – a desirable development for Bangladesh export prospects (Table 1.2).

First: there is now a growing recognition that the worldwide battle against inflation has largely been won (…. but not in Bangladesh yet). After peaking at 9.4 percent year over year in the third quarter of 2022, headline inflation rates are now projected to reach 3.5 percent by the end of 2025 (See: Fig. 1.1), below the average level of 3.6 percent between 2000 and 2019. This has motivated key central banks, such as the FED in the United States and ECB in the European Union, to announce multiple cuts in their respective interest rates in 2024, which is likely to reduce pressure on the exchange rate of developing countries (like Bangladesh) against the US dollar- easing our own management of the inflationary pressure by mitigating the problem of imported inflation. Second: given global growth is likely to remain steady at 3.2% – while growth in advanced economies is expected to remain steady at 1.8%, it should aid the resurgence of our exports and remittances. Besides, what appears heartening to note is that the projected rate of trade growth for 2025 is 3.4%, which is expected to mildly outperform world output growth in 2024 – a desirable development for Bangladesh export prospects (Table 1.2).

Furthermore, as things stand, it is challenging to even predict what the Trump leadership will mean for developing counties like Bangladesh. At one end, there is a definite possibility that Trump’s overall geo-political agenda will be to economically contain the rise of China through the imposition of tariff centric trade barriers, which can trigger the relocation of export oriented economic enterprises from China to Bangladesh and elsewhere. Additionally, if Bangladesh can take advantage of this phenomenon, then exports to the US will receive a new stimulus. At the other end, it is possible but less likely that Trump will opt for the imposition of wholesale trade protection, which will complicate the economic prospects of countries like Bangladesh, whose one-fourth export receipts come from the US. Consequently, we have to carefully explore and examine the exact set of policy priorities that dominate the Trump administration – and how we can respond to it. Notwithstanding these developments, FY25 remains a critical juncture for Bangladesh, where reforms on critical economic areas and the careful navigation of the changing global economic dynamics under Trump 2.0 will ultimately influence the resilience of our ongoing economic recovery.

Growth Performance

Bangladesh’s Resilient but Bruised Growth Trajectory

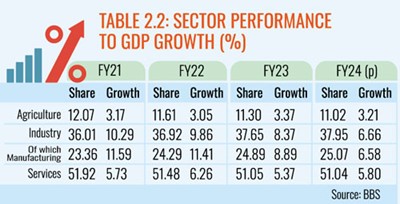

In the recent past, Bangladesh has experienced a volatile growth trajectory, marked by both resilience and setbacks. Table 2.1 highlights the GDP growth rates, comparing Bangladesh’s trajectory with key regional economies: China, India, Pakistan, and Vietnam. From 2019 to 2023, Bangladesh’s economic growth exhibited resilience yet faced significant challenges amid global and domestic pressures. In 2019, GDP growth reached 7.88%, but the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 disrupted this momentum, leading to a sharp contraction to 3.45% as lockdowns and supply chain issues affected nearly all sectors. The economy bounced back in 2021 with a 6.94% growth, driven by renewed domestic demand and exports, and in 2022, growth further edged up to 7.1%. The manufacturing sector, a key growth engine, grew substantially during this period, with expansion rates of 11.59% in 2021 and 11.41% in 2022. This boost was primarily fueled by the export-driven garment industry, which benefitted from global demand recovery alongside improved domestic consumption as COVID-related restrictions eased.

In the recent past, Bangladesh has experienced a volatile growth trajectory, marked by both resilience and setbacks. Table 2.1 highlights the GDP growth rates, comparing Bangladesh’s trajectory with key regional economies: China, India, Pakistan, and Vietnam. From 2019 to 2023, Bangladesh’s economic growth exhibited resilience yet faced significant challenges amid global and domestic pressures. In 2019, GDP growth reached 7.88%, but the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 disrupted this momentum, leading to a sharp contraction to 3.45% as lockdowns and supply chain issues affected nearly all sectors. The economy bounced back in 2021 with a 6.94% growth, driven by renewed domestic demand and exports, and in 2022, growth further edged up to 7.1%. The manufacturing sector, a key growth engine, grew substantially during this period, with expansion rates of 11.59% in 2021 and 11.41% in 2022. This boost was primarily fueled by the export-driven garment industry, which benefitted from global demand recovery alongside improved domestic consumption as COVID-related restrictions eased.

However, in 2023, growth decelerated to 5.78% as global uncertainties, particularly after the Russia-Ukraine conflict, exacerbated energy costs and inflation, thereby increasing production costs and curbing consumer spending. These pressures also undermined the performance within the manufacturing sector, which saw growth drop to 8.89% (Table 2.2) due to rising input costs, energy shortages, and inflationary challenges, all of which weakened profit margins and limited the sector’s growth potential compared to prior years.

For FY24, a provisional GDP growth rate of 5.82% was projected, but quarterly estimates are indicative that this target may not be met, as quarterly GDP growth rates average 5.0%. Growth started at 6.04% in the first quarter but dropped consistently to 3.91% by the fourth quarter (See Table 1.1), reflecting vulnerabilities across sectors. It is also likely that the tightened monetary policy framework and the associated import compression strategy undertaken in FY24 to contain stubbornly high inflation and stabilize Balance of Payments (BOP) by halting the depletion of foreign reserves is having its expected implication on economic activities. The manufacturing sector, in particular, faced sharp declines, with a negative contribution of (-) 1.18% in the second quarter, signaling strain from high input costs, energy constraints, and muted export performance. The services sector mirrored this decline, while agriculture showed modest gains, rising from a 0.35% growth in the first quarter to a peak of 5.27% in the fourth. However, this late recovery is insufficient to offset the broader economic slowdown, especially as agriculture faces climate-related disruptions, such as recent floods that have hurt crop yields and driven up food prices.

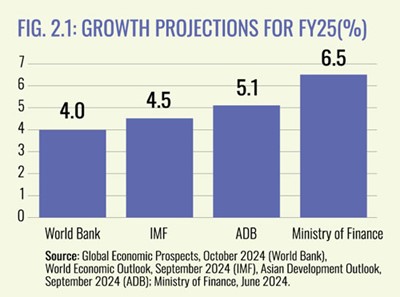

Bangladesh’s economic arena in recent times has been further plagued by a turbulent political climate, macroeconomic imbalances, and balance of payments challenges, all of which erode investor confidence and dampen private sector activity. Imperfect macroeconomic responses in both the fiscal and monetary front have intensified these vulnerabilities. Consequently, growth projections by major development partners have been substantially downgraded with the most optimistic scenario projected by ADB (See: Fig. 2.1). Yet, this relatively bruised growth trajectory for FY25 will not raise any alarm within the policymaking arena provided the undertaken contractionary fiscal and monetary policy measures stabilize the overall macroeconomic scenario over the coming months.

Bangladesh’s economic arena in recent times has been further plagued by a turbulent political climate, macroeconomic imbalances, and balance of payments challenges, all of which erode investor confidence and dampen private sector activity. Imperfect macroeconomic responses in both the fiscal and monetary front have intensified these vulnerabilities. Consequently, growth projections by major development partners have been substantially downgraded with the most optimistic scenario projected by ADB (See: Fig. 2.1). Yet, this relatively bruised growth trajectory for FY25 will not raise any alarm within the policymaking arena provided the undertaken contractionary fiscal and monetary policy measures stabilize the overall macroeconomic scenario over the coming months.

The end of the Awami League regime comes with economic disorder and uncertainties of various kinds. In 1990 when the military regime fell after a reign of 10 years, the economy was in shambles. The July Revolution changed the course of history but it has created uncertainties in the business environment from which it will take time to recover fully. Typically, investment is among the main casualties of the business sector. Investors weigh risks and returns based on the prevailing and evolving investment climate. Macroeconomic stability and policy continuity are fundamental features of a dynamic investment climate. Tectonic shifts in the political sphere since July-August coupled with the banking sector debacle are proving to be menacingly disconcerting for investment activity. A rejuvenation of the business and investment environment on a fast track should be an absolute policy priority.

The end of the Awami League regime comes with economic disorder and uncertainties of various kinds. In 1990 when the military regime fell after a reign of 10 years, the economy was in shambles. The July Revolution changed the course of history but it has created uncertainties in the business environment from which it will take time to recover fully. Typically, investment is among the main casualties of the business sector. Investors weigh risks and returns based on the prevailing and evolving investment climate. Macroeconomic stability and policy continuity are fundamental features of a dynamic investment climate. Tectonic shifts in the political sphere since July-August coupled with the banking sector debacle are proving to be menacingly disconcerting for investment activity. A rejuvenation of the business and investment environment on a fast track should be an absolute policy priority.

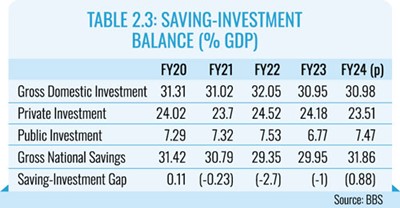

Table 2.3 tracks developments in the savings-investment balance of the economy. Bangladesh, as an LMIC, continues to rely on investment-driven growth. Though Bangladesh’s overall investment rate at 31% of GDP is comparable to its peers, it still falls short of the required rate for achieving growth acceleration to 7-8% on a sustainable basis. What is striking is that Gross Domestic Investment (GDI) has remained static for the past 4-5 years. Even more disconcerting is the fact that private investment has been on a modest decline when the economy’s dynamism depends on private domestic and foreign investment. Public investment has meanwhile compensated for the this declines with massive investments in mega infrastructure projects. This investment composition needs to be turned around with a higher share coming from private and foreign investment. That requires major work on the investment climate front.

Table 2.3 tracks developments in the savings-investment balance of the economy. Bangladesh, as an LMIC, continues to rely on investment-driven growth. Though Bangladesh’s overall investment rate at 31% of GDP is comparable to its peers, it still falls short of the required rate for achieving growth acceleration to 7-8% on a sustainable basis. What is striking is that Gross Domestic Investment (GDI) has remained static for the past 4-5 years. Even more disconcerting is the fact that private investment has been on a modest decline when the economy’s dynamism depends on private domestic and foreign investment. Public investment has meanwhile compensated for the this declines with massive investments in mega infrastructure projects. This investment composition needs to be turned around with a higher share coming from private and foreign investment. That requires major work on the investment climate front.

Poverty Alleviation Momentum Hitting Rough Waters

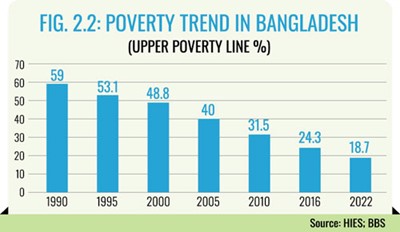

Bangladesh’s national poverty rate has experienced substantial decline, dropping from 59% in 1990 to 18.7% in 2022 (Figure 2.2). This progress in poverty reduction is attributed to sustained economic growth, social programs, buoyant export and manufacturing sector and targeted policies. Comparatively, Bangladesh outperformed India and Pakistan, though China achieved an even more dramatic drop, reducing poverty from 66% in 1990 to below 1% by 2020 through rapid economic growth and rural reforms. Vietnam also made significant strides, reducing poverty from 58% in 1993 to 5% by 2020, driven by market reforms and agricultural growth.

What is more striking is that during the same period (1990-2019), income inequality has been rising precariously revealing the inequitable distribution of gains from economic progress. The omnibus measure of income inequality, the Gini coefficient, rose from 0.39 in 1990 to 0.49 in 2019, according to BBS. Gini coefficients of 0.4-0.5 are considered to be signals of high inequality that raises social and political tensions, as we have experienced over the past year.

Despite Bangladesh’s progress, recent challenges-including the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ukraine-Russia conflict, and high inflation-have hampered further poverty reduction efforts. The Ukraine crisis disrupted global supply chains, driving up input and food prices and fueling inflation that eroded purchasing power thus exacerbating food insecurity as well as poverty. While government interventions provided some relief, they were often short-lived, so that the absolute number of people in poverty could be roughly projected in the range of 30-40 million today.

With persistent inflation interwoven with political disruptions, strengthening social protection has become a national priority. To make further progress in poverty alleviation, Bangladesh’s social security framework needs substantial reform to address funding shortfalls, inefficient targeting, and regional disparities. Current budget allocations fall short of the National Social Security Strategy (NSSS) goal of 3% of GDP, restricting the effectiveness of poverty reduction measures. Increasing investment, optimizing fund allocation, and fostering public-private partnerships are crucial to expanding the scope and impact of poverty programs. Additionally, international support could fill budgetary gaps, while stronger institutional coordination is essential for effective targeting. Policy inconsistencies and political challenges continue to impede full NSSS implementation; overcoming these through strategic restructuring is vital for sustained poverty reduction and resilience.

Monetary management, Inflation and Banking Sector Challenges

The Inflationary Pressure Remains Stubborn

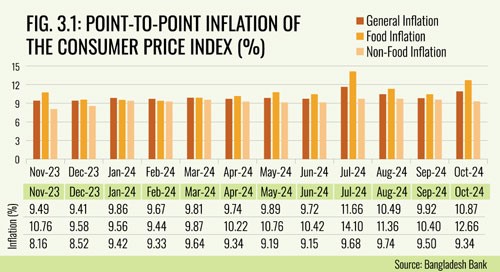

Bangladesh has been experiencing stubbornly high inflationary pressure for at least last 24 months. In fact, monthly inflation reached as high as 11.66% in July 2024, especially due to the nationwide disruptions from the July Revolution, and still remains stubbornly high at 10.87% in October 2024. It is also worth noting that while non-food inflation has remained moderately tolerable, the upward pressure on the inflation arithmetic is primary driven by food inflation, which remains sensitive to shocks from political instabilities, market collusions and natural calamities – such as the severe flash floods that marooned a large part of the eastern and southeastern belt in the late end of August 2024. It is also essential to underscore that inflation estimations in the post July Revolution are not being subjected to manipulation to under-report the problem.

Even so, for the past two years, around 10% inflation has been a persistent feature of the Bangladesh economy. Lessons from economic history vividly demonstrates that high inflation can hinder macroeconomic stability, erode competitiveness of local entrepreneurs, demotivate investment decisions, and accentuate income inequality by substantially reducing the purchasing power of fixed-income and financially weak households. Thus, it is not surprising that mature monetary regimes across advanced economies commit to an inflation targeting framework where the primary agenda is to keep inflation at about two percent annually. This also explains why central banks across advanced economies have responded aggressively to tighten the money supply and raise the interest rate, which translated into lowering the inflationary pressure in their respective economy.

In contrast, it is worth exploring why inflation in Bangladesh has maintained a stubbornly high trend since mid-2022, even though global inflation has been coming down over the last 24 months? In other words, why is inflation in countries like India hovering around 6% (while Sri Lanka is recently experiencing deflation) yet it remains above 10% in Bangladesh? What explains this apparent disturbing divergence? If we examine the source of this problematic macroeconomic scenario, it is evident that a confluence of international and domestic factors has underpinned this unfortunate scenario. For instance, there is now a consensus among experts that across advanced economies excessive fiscal and monetary stimulus in response to Covid-19 along with the supply-chain disruptions stemming from the aftershocks of Covid-19 induced pent-up demand and Ukraine-Russia War originally fueled this spike in inflation across countries.

In Bangladesh, the drivers are not so much different. According to the Monetary Policy Statement (MPS) published by Bangladesh Bank in January 2024, our inflationary pressure was initially fueled by three key factors: {i} supply-chain disruptions stemming from the Ukraine-Russian war {ii}a steep depreciation in the exchange rate in FY22 and FY23; and {iii} a sharp energy prices adjustments after the Ukraine-Russia war. Of course, this narrative ignored critical domestic factors that undermined the management of the inflationary pressure, which has increasingly received recognition among analysts.

These are: {i} the decision to keep interest rate structure fixed within the 6-9% band – ignoring the global developments and the post-Covid surge in domestic and international inflation; {ii} keeping the exchange rate virtually fixed against the dollar for a long period contributing to a massive balance of payments imbalance resulting in a sharp depreciation of Taka (from Taka 86 per US$ in FY22 to Taka 120 per US$ in September 202); {iii} printing of high-powered money by Bangladesh Bank for lending to the government to compensate for revenue shortfall in FY2023 (the Treasury borrowed Taka 98,000 Crore directly from Bangladesh Bank in FY23); and {iv} injection of emergency funds through promissory notes into troubled Islamic Banks in Dec-2022, Dec-2023 and June 2024, partially off-setting the efficacy of the contractionary monetary policy stance of Bangladesh Bank.

Collectively, both the inadequacy of macroeconomic management and unfavorable international scenario allowed inflation to remain stubbornly high in Bangladesh (Fig. 3.1) in comparison to countries like India or Sri Lanka in the region over the last 12 months.

Collectively, both the inadequacy of macroeconomic management and unfavorable international scenario allowed inflation to remain stubbornly high in Bangladesh (Fig. 3.1) in comparison to countries like India or Sri Lanka in the region over the last 12 months.

Additional Monetary Policy Tightening in FY24 & Favourable International Outlook

The previous reluctance to apply monetary policy tightening to tame the inflationary pressure and stabilize the tension within the Balance of Payments received notable correction in FY24-25, as the so-called execution of un-orthodox measures of import restriction, etc. did not produce the desired dividend for policymakers. Accordingly, during the first half of FY24, the Bangladesh Bank took a number of policy actions in response to tame the stubborn inflationary pressures.

These actions included: (i) Bangladesh Bank’s decision to raise the policy rate by 175 basis points overall between July and December 2023; (ii) the elimination of the 6-9% interest rate band – and later the Six-Month Moving Average Rate of Treasury Bill (SMART) for market-based management of the interest rate; and (iv) the ceasing of direct lending to the Treasury to finance budget deficit by printing high-powered money. The policy rate was further raised to 10% as of October FY24 to tighten the monetary framework, which is now within touching distance of the inflation rate of 10.87%.

On the international front, there is now an acknowledgement that the global fight against inflation has seen visible progress. After peaking at 9.4 percent in the third quarter of 2022, headline inflation rates are now projected to reach 3.5 percent by the end of 2025, below the average level of 3.6 percent between 2000 and 2019. This has motivated key central banks, such as the FED in the United States and ECB in the European Union, to announce several cuts in their respective interest rates in 2024, which is likely to reduce pressure on the exchange rate of developing countries (like Bangladesh) against the US dollar- easing our own management of the inflationary pressure by mitigating the problem of imported inflation.

An important caveat needs to be added here. While orthodox monetary measures are the appropriate instruments for controlling demand-pull inflation, two factors may undermine the overall effectiveness of such measures in controlling inflation: (i) monetary transmission mechanism is much weaker in the Bangladesh economy because of low monetization and other market failures; and (ii) Bangladesh inflation is a combination of demand-pull and cost-push factors that require simultaneous action on the supply side as well, failing which supply-side factors (e.g. import restrictions, hike in input prices due to exchange rate depreciation) could exacerbate inflationary forces.

There is no doubt that containing inflation is a tough task that will take at least another 9-12 months before we can see notable results. Patience is called for on all sides.

Taming the Inflationary Pressure Through Trade Policy (tariff) Measures

The prevailing inflationary pressure has already prompted calls for the Interim Government (IG) to do much more than Open Market Sales (OMS) through its Trading Corporation of Bangladesh (TCB) to alleviate the plight of the people. Since the tightening of the Monetary Policy by the Bangladesh Bank is yet to provide its dividend, the IG has decided to shift its gear and use trade policy instruments to further aid the existing monetary policy arrangement. Note that tariffs are up nearly 40% (equivalent to exchange rate depreciation over two years) across-the-board without any action on the part of the National Board of Revenue (NBR).

Accordingly, NBR decided to lower the Customs Duty (CD) on the imports of rice from 62.5% to 25% and published Statutory Regulatory Orders (SRO) in that regard. When this step did not yield the downward pressure on prices that was expected, the NBR withdrew the Import Duty on rice altogether – in addition to lowering of Advanced Income Tax (AIT) on the imports of rice to 2% from 5%. At the same time, the Ministry of Food has initiated steps for the import of rice by Open Tender Method (OTM) under G2G deals with Myanmar and Vietnam. Hence, the Advisory Committee on Government Purchases has eased rules for the public procurement of rice – reducing the required time to 15 days from 42 days. Taking note of the fact that the prices of other food items are also getting out of reach, the NBR lowered the CD on eggs to 13% from 30% – while the CD on edible oil was reduced by 5%. Moreover, the Value-Added Tax (VAT) on the production and distribution of edible oil was also withdrawn.

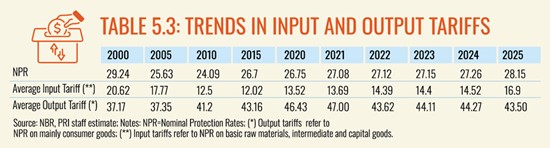

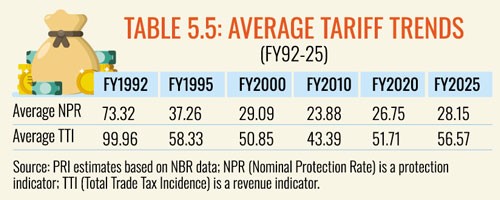

Given the sharp exchange rate depreciation (40%) witnessed over the past two years and the fact that average tariffs are significantly above those of low-income (LIC) and lower middle-income (LMIC) economies, Bangladesh’s tariff structure is crying for a second round of reforms (rationalization) after the first-round of 1990s reforms, albeit incomplete, proved effective in stimulating export performance and growth.

Taken together, these measures are expected to aid the overall effort to tame the existing inflationary pressure over the next 9-12 months, provided the economic space does not experience any adverse political, natural or undesirable energy shocks that disrupt the existing supply-chain arrangements.

The Perilous State of the Banking Sector -Some Recent Signs of Hope

It is now legend how Bangladesh’s banking sector – the beating heart of the economy – was subject to mega-looting by kleptomaniacs of the kind never seen in this country’s history nor in any other country in history. The amounts siphoned off from a number of banks are mindboggling. And now it is being revealed by Bangladesh Bank that such massive theft and associated money laundering to distant shores could not have happened without the full endorsement of the highest authorities in the country. There is little doubt that a part of the sharp depletion of foreign exchange reserves could be attributed to the Hundi mechanism that was used to transfer these ill-gotten funds to safe havens abroad with the result that precious foreign exchange that would have augmented official forex reserves never materialized. A concerted effort is on to leverage international money laundering laws, with the cooperation of Governments of the USA and UK and multilateral institutions like the World Bank and IMF, to retrieve as much of the laundered funds as possible. The road is long and hard. But it is worthwhile.

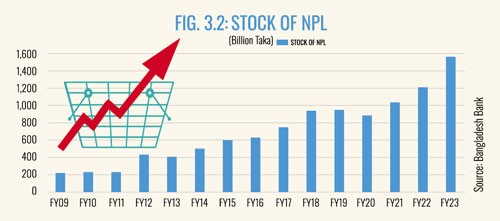

Be that as it may, the banking industry in Bangladesh is currently experiencing the most tenuous scenario ever in its living history. The sector is beset by: (i) growing non-performing loans (NPLs), which pose a serious threat to the sector’s solvency due to their consistently high levels; (ii) liquidity shortages within at least ten extremely troubled banks who were mercilessly plundered by political connected economic oligarchs, which is hindering their capacity to satisfy their depositor demands; (iii) the broader macroeconomic stress, which is creating additional pressure on the overall banking sector and the private entrepreneurs who are navigating a grim economic space for more than two years; and (iv) a stubbornly high inflationary situation, which is limiting Bangladesh Bank’s capacity to bailout the troubled banks through the creation and injection of high-powered money.

Moreover, at the end of 2023, the country’s distressed loans, a sum of non-performing loans, rescheduled loans and restructured write-offs, stood over Tk 4,750 billion, which was 32 percent of the total outstanding bank loans and close to the operating expenditure of the 2023-24 national budget. Furthermore, recent estimates of non-performing loans (NPL) in Bangladesh’s banking sector have soared to a historic high of Tk 2,849 billion in September 2024, accounting for around 17 percent of total outstanding loans. It is also worth noting that in June 2009, non-performing loans (NPL) in Bangladesh stood at Taka Tk 222 billion – underscoring a 13-fold nominal rise in the last 15 years (Fig.3.2).

Moreover, at the end of 2023, the country’s distressed loans, a sum of non-performing loans, rescheduled loans and restructured write-offs, stood over Tk 4,750 billion, which was 32 percent of the total outstanding bank loans and close to the operating expenditure of the 2023-24 national budget. Furthermore, recent estimates of non-performing loans (NPL) in Bangladesh’s banking sector have soared to a historic high of Tk 2,849 billion in September 2024, accounting for around 17 percent of total outstanding loans. It is also worth noting that in June 2009, non-performing loans (NPL) in Bangladesh stood at Taka Tk 222 billion – underscoring a 13-fold nominal rise in the last 15 years (Fig.3.2).

Of course, it is essential to underscore that these adverse political economy developments or the by-products of the crony-capitalist political nexus within the banking sector have received serious attention by the Bangladesh Bank in the aftermath of the July-August Revolution. In particular, after the assumption of office by the Interim Government, Bangladesh Bank has taken a wide array of measures to restore confidence in the banking sector.

First, it has restructured the boards of all the distressed banks and have changed their management, so that the sector is insulated from the adverse influence of the economic actors who have plundered these banks by exercising their de facto influence in the banking sector. Second, Bangladesh Bank has commissioned reliable audits of the troubled banks to understand their financing needs. Third, Bangladesh Bank is pursuing strategic investor to offload equity shares and assets of previous problematic owners to mitigate liquidity shortages in the troubled banks. All these activities are being overseen by the newly formed Banking Sector Reform Task Force. In the context of asset recovery from home and abroad, which requires a different set of expertise, a separate task force has been constituted. This Task Force includes both state and non-state actors like – BFIU, CID, ACC, Ministry of Law/ Attorney General/ MoFA/TIB. This Task Force is also seeking assistance from the relevant agencies of foreign governments and international experts in supporting the recovery process. Furthermore, given initial estimates indicate that at least approximately $17 billion have been laundered from the banking sector, these set of measures can potentially culminate into asset freezing orders in international jurisdictions within the next six months, which will incrementally correct an essential moral hazard problem within the global economy – where influential economic actor plunder their national wealth and launder their assets to international tax havens through illicit financial flows with impunity.

On the whole, these critical measures are likely to restore both confidence in the banking sector and optimal governance practices and structures provided the conspicuous regulatory commitment that the banking sector is presently receiving from Bangladesh Bank is sustained over time – and the regulatory commitment to governance structures within the banking sector is not undermined under political influence in the future.

Fiscal Management and Debt Dynamics

Fiscal Space is Limited but Debt Burden Remains Manageable

In recent years, Bangladesh has navigated a difficult fiscal landscape, shaped by the dual pressures of global economic disruptions and limited domestic resources. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government’s fiscal deficit was projected to rise due to stimulus packages meant to cushion the economy. However, fiscal prudence kept the actual deficit at 5.5% in FY20, a cautious stance that maintained fiscal stability but underscored a structural issue: inadequate revenue generation continues to limit the government’s capacity to support critical investments in infrastructure and human capital. However, since then, the actual budget deficit has remained below 5% for the following three years. Furthermore, given that economic stabilization became the central focus of policymakers in FY24, fiscal management was aligned with the contractionary monetary policy framework to tame the inflationary pressure and halt the depletion of foreign reserves. This resulted in the actual fiscal deficit reaching only 3.7% of GDP, as Bangladesh Bank refrained from directly lending to the Treasury.

It is, nonetheless, essential to underscore that Bangladesh’s development spending is heavily reliant on the size of the fiscal deficit as the development expenditure is generally financed through domestic and international borrowing; a typical syndrome largely observed within developing countries. This underscores our dependence on borrowed funds rather than domestic revenue to support public investments in infrastructure, social security and human capital. This approach has some adverse repercussions, as it restricts the Treasury’s ability to invest in long-term priorities like human capital and infrastructure. Without expanding the fiscal space, Bangladesh risks falling into a cycle of under-investment that could dampen productivity, slow economic resilience, and impede improvements in living standards.

The past two years have been especially challenging for the fiscal sector, largely due to growing pressure in the external sector and the associated macroeconomic stress. A widening current account deficit forced the government to impose import restrictions to safeguard foreign reserves. While this somewhat narrowed the trade deficit, it pushed up inflation – as the steep depreciation of Taka against US dollars made imports costlier. Consequently, the central bank had to abandon the “6/9” interest rate cap and go for higher policy rates. These moves, collectively, offered some support to stabilize the macroeconomic scenario but it raised the borrowing costs for the Treasury, affecting both public and private debt. As Taka experienced a steep depreciation in both FY23 and FY24, debt servicing costs for external loans have surged, absorbing a larger share of the domestic resources. Higher domestic interest rates have further increased the costs of local financing. In FY24, debt servicing alone grew by an estimated 25%, consuming resources that could otherwise support development spending and constraining fiscal space more than ever.

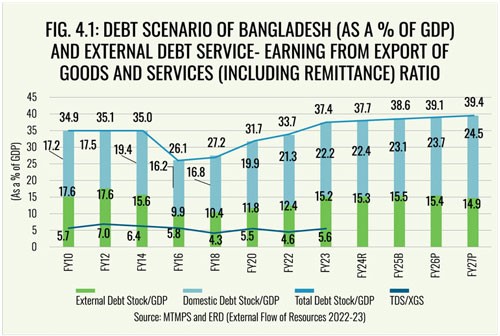

However, Bangladesh’s debt servicing requirements remain manageable, given foreign debt servicing burden still only amounts to less than 6% of our foreign exchange earnings from exports and remittances. Besides, the overall debt burden (See: Fig. 4.1) stands below 40% of GDP (of which external debt accounts for approximately 15%), which is far below countries like Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and India, where total public debt ranges between 80 to 104%. According to IMF-World Bank’s debt sustainability framework for low- income countries, Bangladesh’s risk of external debt distress and risk of overall debt distress also remains low.

However, Bangladesh’s debt servicing requirements remain manageable, given foreign debt servicing burden still only amounts to less than 6% of our foreign exchange earnings from exports and remittances. Besides, the overall debt burden (See: Fig. 4.1) stands below 40% of GDP (of which external debt accounts for approximately 15%), which is far below countries like Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and India, where total public debt ranges between 80 to 104%. According to IMF-World Bank’s debt sustainability framework for low- income countries, Bangladesh’s risk of external debt distress and risk of overall debt distress also remains low.

In other words, the alarmist narrative that often categorizes our present debt burden as unsustainable is categorically incorrect, even though it is essential to take into cognizance that both domestic and international debt servicing obligations is increasingly taking up a higher share of our national revenue. This necessitates that the Interim Government re-examines the existing debt obligations and carefully manage the debt servicing burden for the immediate future, so that the undertaken policy measures can better support the debt obligations in the future.

Revenue Mobilization Capacities and ADP Performance Remain Weak

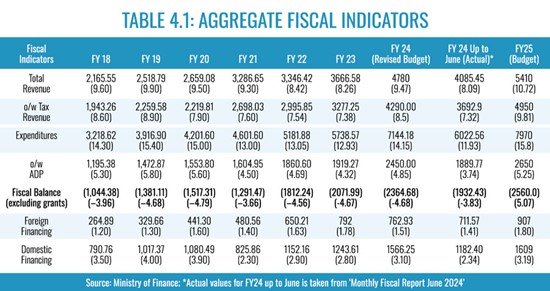

Revenue collection has long been a weak link in Bangladesh’s fiscal sector. This effectively means that the tax-to-GDP ratio has stagnated around 8% for a decade, one of the lowest in the region (See: Table 4.1). This also limits the resources Bangladesh can mobilize for investments in key public goods such as institutions, infrastructure and human capital. Moreover, in spite of the grandstanding political and administrative rhetoric drummed-up over the years, very few effective measures have been adopted by the NBR to effectively alter the existing revenue structure. More precisely, Bangladesh’s tax structure has remained heavily dependent on indirect taxes, such as VAT and import duties, which comprise approximately 70% of total revenue. This regressive tax structure places a disproportionate burden on lower-income groups while shielding wealthier individuals, worsening income inequality. High tariffs also create an anti-export bias by raising costs for domestic businesses, deterring exports and fueling inflation. A rebalanced tax system, including lowered tariffs and a greater reliance on direct taxes, could alleviate inflationary pressures and foster a more competitive business environment

Revenue collection has long been a weak link in Bangladesh’s fiscal sector. This effectively means that the tax-to-GDP ratio has stagnated around 8% for a decade, one of the lowest in the region (See: Table 4.1). This also limits the resources Bangladesh can mobilize for investments in key public goods such as institutions, infrastructure and human capital. Moreover, in spite of the grandstanding political and administrative rhetoric drummed-up over the years, very few effective measures have been adopted by the NBR to effectively alter the existing revenue structure. More precisely, Bangladesh’s tax structure has remained heavily dependent on indirect taxes, such as VAT and import duties, which comprise approximately 70% of total revenue. This regressive tax structure places a disproportionate burden on lower-income groups while shielding wealthier individuals, worsening income inequality. High tariffs also create an anti-export bias by raising costs for domestic businesses, deterring exports and fueling inflation. A rebalanced tax system, including lowered tariffs and a greater reliance on direct taxes, could alleviate inflationary pressures and foster a more competitive business environment

In FY24, total revenue collection reached BDT 4,085 billion, or only 85.5% of the revised target of BDT 4,780 billion. Despite a 11.4% year-over-year increase, the revenue-to-GDP ratio remained at just 8.09%, with the tax-GDP ratio at 7.32%-underscoring the ongoing challenges in tax administration and collection. On the expenditure front, recurrent costs such as wages, subsidies, and debt servicing consume over 65% of the budget. In FY24, 42% of recurrent spending went toward subsidies and transfers, while debt servicing accounted for 28%, exceeding initial allocations due to rising interest rate costs. These spending patterns further limit Bangladesh’s ability to expand development expenditures. Without a substantial increase in tax revenue, the government’s options for financing essential obligations remain limited.

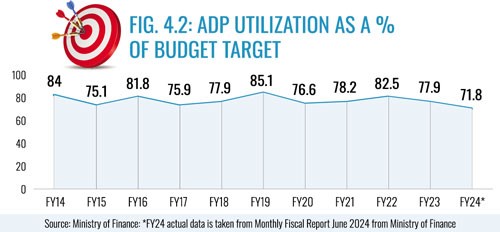

Implementation of the ADP has also appeared increasingly weak over time, with an average of only 78% of budgeted funds utilized over the last decade (See: Fig. 4.2). In FY24, ADP implementation fell further to 72% due to political uncertainties associated with the national election in January 2024, inefficiencies and funding constraints. Furthermore, the first quarter of FY25 experienced the lowest ADP implementation rate in last fifteen years, as recent political unrest has caused additional project delays and cancellations. To maintain fiscal stability and to reduce borrowing from the banking sector, the Interim Government also planned to drop or postpone a large number of development projects, which will also allow fiscal policies to closely align with the contractionary monetary policy stance. This state of affairs, nevertheless, highlights an urgent need to mobilize more domestic resources to finance critical public investments and strengthen resilience against external shocks.

Therefore, to address the revenue shortfall, Bangladesh must expand its tax base, reduce exemptions, improve VAT compliance, and strengthen the financial health of state-owned enterprises. Additionally, reallocating limited fiscal resources toward high-impact sectors like education, healthcare, and infrastructure can maximize returns on public spending and promote long-term growth. Targeted investments in these areas are crucial for building a resilient economy capable of withstanding shocks and supporting inclusive growth of the kind needed for development in the 21st century (i.e., building a knowledge economy).

External Sector Development

Macroeconomic stability challenged by external developments

Trade has been a strong handmaiden of Bangladesh development. It will have to remain a key driver of economic progress for the long-term. That also means the economy will have to become more integrated with the world economy over time. That raises the potential for disruptions emerging from global developments, something we have experienced since 2020.

More precisely, since 2020, developments in the external sector presented tremendous challenges to macroeconomic stability, which was a strong point for the economy for nearly 25 years. Following reasonably good management of the fallout from Covid-19 pandemic the economy was on a decent recovery track when the Russo-Ukraine war delivered disruptive supply chain shocks that initially led to spike in energy and commodity prices globally with consequent ballooning of Bangladesh’s trade and current account deficits. The economy is yet to completely recover from that shock. However, recent corrective measures in exchange rate management are proving effective in restoring stability in BOP and its components.

Making Sense of the Export Data Conundrum

Exports, particularly RMG exports, has been the golden goose of the Bangladesh economy. Recently, export data came under scrutiny when it rose to $55 billion in FY2024, as exporter associations (BGMEA-BKMEA) began questioning the number. Meanwhile, the Financial Account deficit was ballooning to incomprehensible numbers that needed immediate cross-checking. It has now become evident that the line item within the Financial Account, trade credit, was exploding inexplicably. We now understand that this trade credit was a corrective entry in the financial account to cover the discrepancy between export shipments (recorded by EPB from customs data) and export receipts in BB data. With export shipment data revised to reflect more closely the export receipts, the trade credit figures came down to normal levels and the Financial Account returned to positive, as in the past.

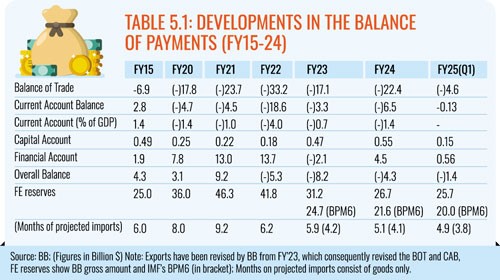

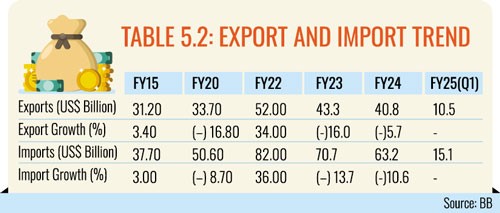

A thorough review of customs data by a team comprising representatives from BB, EPB and NBR/Customs revealed, as a preliminary assessment, the main source of the problem: serial duplication errors in customs data (major problem). Other issues that were identified include: (i) miscalculation of value of fabrics; (ii) sample items classified as products with export value; (iii) sales by EPZ-based firms being counted twice; (iv) failure to adjust the gap between export shipments and actual export receipts; (v) short shipments and some rejections by importers; and (vi) losses from stock-lot sales, discounts, and commission were not being adjusted in the final calculation by EPB. The discrepancies were so massive that export figures had to be adjusted downwards by some $12 billion (25%) for FY2023, resulting in a new export figure of $43.3 billion and $40.8 billion for FY2023 and FY2024, respectively. Thus, we now have sober export figures showing decline of 16% and 5.7%, respectively, for FY23 and FY24 (Table 5.2). That said, exports are on the uptick for Q1 of FY25 recording a modest 5-6 percent growth (See: Table 5.1-5.2).

A thorough review of customs data by a team comprising representatives from BB, EPB and NBR/Customs revealed, as a preliminary assessment, the main source of the problem: serial duplication errors in customs data (major problem). Other issues that were identified include: (i) miscalculation of value of fabrics; (ii) sample items classified as products with export value; (iii) sales by EPZ-based firms being counted twice; (iv) failure to adjust the gap between export shipments and actual export receipts; (v) short shipments and some rejections by importers; and (vi) losses from stock-lot sales, discounts, and commission were not being adjusted in the final calculation by EPB. The discrepancies were so massive that export figures had to be adjusted downwards by some $12 billion (25%) for FY2023, resulting in a new export figure of $43.3 billion and $40.8 billion for FY2023 and FY2024, respectively. Thus, we now have sober export figures showing decline of 16% and 5.7%, respectively, for FY23 and FY24 (Table 5.2). That said, exports are on the uptick for Q1 of FY25 recording a modest 5-6 percent growth (See: Table 5.1-5.2).

Such a massive downward adjustment of export figures creates serious questions of credibility and needs to be resolved in a professional manner. Thankfully, the IMF is offering professional expertise to resolve this issue. A BOP mission is in town for examining the source and nature of the data discrepancies and until we hear from the IMF-BB team on the final assessment we can only take the revised export data for FY23-24 as provisional. Until this data issue is credibly and satisfactorily resolved it would be best to hold judgment on export performance for the past couple of years.

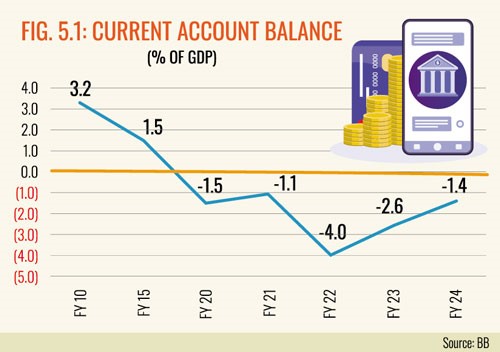

Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that the BOP figures now look more sensible with the Financial Account in positive territory. The current account, which was clearly unsustainable at 4% of GDP in FY2022 has been brought under control at 1.4% of GDP with sharp administrative control of imports (Fig. 5.1). CAD at 4% of GDP was clearly unsustainable. It is a welcome relief to observe that it is back to a sustainable level of 1.4% of GDP. It is essential to point out that a current account deficit (as long as it is sustainable) is not a sign of weakness. Nor is a current account surplus a sign of strength.

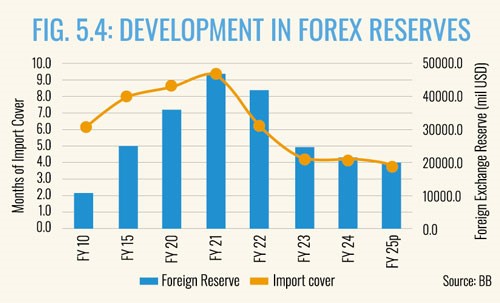

The external sector is still not out of the woods. As the overall BOP balance continues to be negative, the FE reserve position is still under stress, whether we use BB official reserves data ($25.7B) or IMF’s BPM6 construct ($20.0B). Absent is the comfortable reserve situation of 9 months import cover which was the case in FY21.

Exchange rate management: BB has adopted a crawling peg system, which is a flexible market-based approach. Exchange Rate of Taka against USD has stabilized at Taka 120 and foreign reserves – according to BMP6 – have stabilized at around $19-20 Billion. This is indicative that the contractionary monetary policy and the associated fiscal policy is bringing order to Balance of Payments. Increased market-based exchange rate and monetary policy management is collectively bringing an improvement in BOP, minimizing exchange rate volatility and bringing a near halt to the forex reserve depletion over the last 12 months. This process was also aided by IMF’s support of $4.7 billion over a period of 42 months beginning in January 2023, which added credibility to the overall policy process. On the whole, the panic and the volatility that was observable within Bangladesh’s external sector in FY22 and FY23 has mostly stabilized in the tail end of FY24, and it is likely to create favorable conditions for growth and stability in the near future – as the prevailing policy avenue is likely to be maintained in FY25 by the Interim Government to support the overall stabilization of the economy.

Export, Import and Remittance in the Current Scenario

After falling for two consecutive years, export performance is now on the mend, despite the initial disruptions caused by the recent upheaval which caused several problems for exporters as they faced difficulty in the procurement of raw materials, faced energy crisis in the industrial zone, including some work stoppages, resulting in slow industrial activity and low shipment of Ready-Made Garments. That phase is now over and exports are off to a good start as indicated by 5-6% growth in Q1 of FY25.

After falling for two consecutive years, export performance is now on the mend, despite the initial disruptions caused by the recent upheaval which caused several problems for exporters as they faced difficulty in the procurement of raw materials, faced energy crisis in the industrial zone, including some work stoppages, resulting in slow industrial activity and low shipment of Ready-Made Garments. That phase is now over and exports are off to a good start as indicated by 5-6% growth in Q1 of FY25.

On the other hand, imports have slowed down considerably since FY2023 due to administrative controls (e.g., restrictions on LC opening) in the past and tight monetary policy now. Imports decreased by 10.6 percent (y-o-y) during FY24, relative to FY23 (Table 5.2) and the decrease is prevalent in Q1 of FY25, which is not a good sign for economic recovery. The fall in imports was an outcome of the price effect of Taka depreciation, several austerity measures imposed by the Bangladesh Bank, tight monetary and interest rate policy, and slowdown of the economy. As an exporter of predominantly manufactured goods, import reliance is not a sign of weakness but a natural outcome of the export-led growth strategy. Since CAD has been sustainable for a long period, it shows that Bangladesh is capable of financing its rising imports through export and remittance earnings of foreign exchange without going broke.

On the other hand, imports have slowed down considerably since FY2023 due to administrative controls (e.g., restrictions on LC opening) in the past and tight monetary policy now. Imports decreased by 10.6 percent (y-o-y) during FY24, relative to FY23 (Table 5.2) and the decrease is prevalent in Q1 of FY25, which is not a good sign for economic recovery. The fall in imports was an outcome of the price effect of Taka depreciation, several austerity measures imposed by the Bangladesh Bank, tight monetary and interest rate policy, and slowdown of the economy. As an exporter of predominantly manufactured goods, import reliance is not a sign of weakness but a natural outcome of the export-led growth strategy. Since CAD has been sustainable for a long period, it shows that Bangladesh is capable of financing its rising imports through export and remittance earnings of foreign exchange without going broke.

Remittance, too, marked a 10.6 percent increase in FY24, recording inflows of $23.9 billion. The surge in remittance could be attributed to factors such as the introduction of the crawling peg exchange rate system, banks offering up to 2.5 percent on inward remittances, on top of the existing 2.5 percent incentive, prompting expatriates to remit more through the formal channel than informal channels (hundi). As the gap between the formal and the curb market rate came to a mere 2 percent, an inflow of $23.9 Billion remittance was recorded for FY24, enough to compensate for a trade deficit of $22 Billion (See: Table 5.1). Indeed, it is notable that remittance inflows recorded a whopping 30 percent growth in Q1 of FY25. This upsurge can be clearly attributed to the complete reversal of policy messages to the critical players in the world of remittances. The profligacy, malfeasance, and massive money laundering activities that reportedly occurred during the previous government came to an abrupt end with the Interim Government taking charge. Remittance, which makes up over 6% of GDP, continues to be a key driver of the economy (as a record 1.3 million migrant workers left the country on FY2024) with a significant impact on growth and poverty reduction. If the quarterly remittance performance is any signal of what is to come, the economy may see a robust rise in remittance to over $30 billion by end of the fiscal year. That could give a major boost to FE reserves besides being a major source of import financing (Fig. 5.3-5.4)

Remittance, too, marked a 10.6 percent increase in FY24, recording inflows of $23.9 billion. The surge in remittance could be attributed to factors such as the introduction of the crawling peg exchange rate system, banks offering up to 2.5 percent on inward remittances, on top of the existing 2.5 percent incentive, prompting expatriates to remit more through the formal channel than informal channels (hundi). As the gap between the formal and the curb market rate came to a mere 2 percent, an inflow of $23.9 Billion remittance was recorded for FY24, enough to compensate for a trade deficit of $22 Billion (See: Table 5.1). Indeed, it is notable that remittance inflows recorded a whopping 30 percent growth in Q1 of FY25. This upsurge can be clearly attributed to the complete reversal of policy messages to the critical players in the world of remittances. The profligacy, malfeasance, and massive money laundering activities that reportedly occurred during the previous government came to an abrupt end with the Interim Government taking charge. Remittance, which makes up over 6% of GDP, continues to be a key driver of the economy (as a record 1.3 million migrant workers left the country on FY2024) with a significant impact on growth and poverty reduction. If the quarterly remittance performance is any signal of what is to come, the economy may see a robust rise in remittance to over $30 billion by end of the fiscal year. That could give a major boost to FE reserves besides being a major source of import financing (Fig. 5.3-5.4)

Trade prospects in FY2025

As a new chapter unfolds in Bangladesh’s onward journey, trade must remain a strong handmaiden of its development, as it has been in the past. To conclude, despite the youth-driven upheaval, the key drivers of the economy remain very much intact and ready to take the economy to new heights. First, the readymade garment industry has by and large remained unscathed with export prospects unaltered and perhaps better in the coming year as China+1 geoeconomics, a global strategy of diversifying supply chains, takes deeper root. Second, remittances are already showing signs of resurgence to be commensurate with the fact that departure of migrant workers has doubled in recent years and continues to remain strong. Third, agriculture, a sector that has taken the country towards food self-sufficiency, is also transforming itself into a mechanized and viable commercial enterprise of the future. Fourth, NGO-GO partnership for health, education, and human services for which Bangladesh is recognized the world over, gets a new boost with an NGO pioneer at the helm of affairs. These key drivers present opportunities as well as challenges, with occasional hiccups to be expected.

Persistence of Anti-export Bias hobbles export diversification

While exchange rate management has been slowly moved into a quasi-flexible exchange rate regime recently, the crux of the problem now lies in the tariff structure which remains high and complex when world tariffs are down to an average of 5-6%, while that of lower middle-income countries (LMIC) is 7%, compared to Bangladesh’s average tariff of 28% (See: Table 5.3).

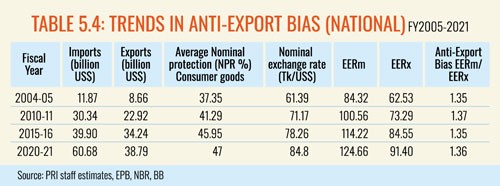

High protective tariffs make import-substitution activity more profitable than exports thus making the latter less attractive. Table 5.4 gives overall trend in anti-export bias showing incentives are about 35-37% higher for domestic sales compared to exports. RMG sector, being 100% export-oriented are not affected by tariff policy. This anti-export bias of policy undermines incentives for expansion of non-RMG exports (Table 5.4). The tariff and protection structure has become a binding constraint to export diversification, which is pretty much halted with export concentration on the rise.

High protective tariffs make import-substitution activity more profitable than exports thus making the latter less attractive. Table 5.4 gives overall trend in anti-export bias showing incentives are about 35-37% higher for domestic sales compared to exports. RMG sector, being 100% export-oriented are not affected by tariff policy. This anti-export bias of policy undermines incentives for expansion of non-RMG exports (Table 5.4). The tariff and protection structure has become a binding constraint to export diversification, which is pretty much halted with export concentration on the rise.

Reform Agenda and Way Forward

Tectonic shift in the Government triggers agenda for economic reforms

The economic reform agenda has been brewing and becoming more complex over the past decade and a half. Reasonably good macroeconomic and export performance over two decades gave rise to policy complacency and stasis. The economy was actually reaping the benefits from the deep-dive reforms and change of policy directions executed during the first part of the 1990s decade. That first round of reforms, incomplete though they were, gave the economy the stimulus to achieve notable growth, job creation and poverty reduction that we have experienced so far.

The economic reform agenda has been brewing and becoming more complex over the past decade and a half. Reasonably good macroeconomic and export performance over two decades gave rise to policy complacency and stasis. The economy was actually reaping the benefits from the deep-dive reforms and change of policy directions executed during the first part of the 1990s decade. That first round of reforms, incomplete though they were, gave the economy the stimulus to achieve notable growth, job creation and poverty reduction that we have experienced so far.

By 2020, however, those reform gains were at the end of their tether. The economy was bruised by the first “Black Swan” event – Covid 19 and its aftermath — followed by the breakout of the Russo-Ukraine war. Underlying weakness of the economy was soon revealed. After a brief reprieve in 2021, the economy has pretty much gone downhill since 2022, marked by high inflation, dwindling foreign exchange reserves, exchange rate volatility, deep-rooted malaise in the banking sector, low and stagnant tax-to-GDP ratio, and dubious expansion in public spending. GDP growth fell far short of targets, with export growth falling in negative territory and foreign and domestic investment showing no traction whatsoever. It takes no expert to attribute this downslide to poor economic management and endemic corruption, especially mega-thefts in the banking sector and corrupt practices in public procurement. It is fair to say now that meaningful economic reforms formed no part of the policy agenda, though national experts and development partners were crying out for sorely needed reforms.

Consequently, the political shifts after the 5th of August have ushered in a great opportunity for the nation to undertake a second round of long-awaited economic reforms. The Interim Government (IG) has worthily taken immediate actions to stem the tide of macroeconomic instability. First, Bangladesh Bank has skillfully put a stop to the theft-related bleeding of the banking sector by making wholesale changes in the affected banks’ management. Second, it fully deregulated the interest rate policy and tightened domestic liquidity by increasing the policy rate. Third, a broad-based fight against corruption, including efforts to recover stolen assets, was announced. Finally, professional management of the exchange rate is generating positive outcomes for higher remittance inflows through official channels, besides stabilizing forex reserves and stimulating exports.

Several other reforms by the IG are now underway including revisiting public spending priorities to cut waste and leakages, reducing corruption and increasing tax collections through online tax filing, lowering duties on essential food imports to reduce inflationary pressure, and mobilizing greater financial assistance from development partners.

Reforms that have just started will take time to yield results. Nevertheless, some visible results can be seen such as the stop to mega-theft from the banking system which, in association with interest rate flexibility, is helping deposit growth. Export and remittances have shown sound recovery during the first quarter of FY2025. However, inflation remains stubbornly high, government revenue collection remains sluggish, and the forex reserves accumulation is still weak due to increased debt payments and a pickup in imports. Negotiations are on with the multilateral institutions for fast release of committed budget and BOP financing.

Taming inflation and restoring stability and governance in the banking sector are the immediate challenge. While demand side measures (monetary tightening) are on track, other measures to augment supply side responses are afoot. These include enhancing imports and augmenting domestic supply, which is intimately linked to the recovery of production, investment and exports. The supply-side agenda is tough and involves both short-term (one to three years) and medium-term (three-plus years) reforms related to skills, technology, domestic investment, foreign direct investment (FDI), and export diversification. Furthermore, measures must also be taken to ensure regulatory autonomy of the Bangladesh Bank, so that better governance standards are attained for the foreseeable future. These encompass policy reforms in many areas. The most immediate reforms include:

Ensure the Autonomy of the Bangladesh Bank: The autonomy of Bangladesh Bank came under severe stress between 2009 and 2024 as measures were taken under the crony-capitalist political nexus to undermine its’ regulatory realm by creating the Financial Institutions Division, which took over the regulatory role for all the state-owned banks. Further blows came from the de facto political patronization of Bangladesh Association of Banks (BAB) – who became extremely instrumental in influencing policies for the overall banking sector. Consequently, the Interim Government must ensure the autonomy of the Bangladesh Bank and insulate it from powerful interest group pressure. Most importantly, its authority over the entire financial sector must not be undermined by any alternative public agency as the financial sector cannot receive effective regulation from multiple bodies. In particular, the Interim Government must seriously consider scrapping the Financial Institutions Division within the Ministry of Finance, so that the entire banking sector (SCBs, PCBs, FCBs and NBFIs) is brought under a single regulator, i.e., the Bangladesh Bank.

Exchange Rate Management: Though exchange rate flexibility has been applied, it is time to move out of the crawling peg mechanism and go for full flexibility of the exchange rate, a measure that brought fast relief to the Sri Lankan BOP crisis as well as inflation. The demand management policies in place will protect the rate from fluctuating wildly. A market-based exchange rate is the best way to provide incentives to exporters and remittance senders. It is also high time to discard the 1947 Foreign Exchange Regulation Act that governs all foreign exchange transactions and restrictions. Working with amendments to this outmoded law is no longer passe. A completely new Act befitting current state of Bangladesh’s international trade and foreign payments is the necessity of the time.

Monetary Management: While monetary policy is broadly on track, a careful review of the T-bill market is essential. The T-bill operation is undermining banking sector dynamism as banks are choosing the easy option of profiting from higher returns from T-bills instead of engaging in low-yielding lending operations.

Fiscal Management: Close coordination between fiscal and monetary operations is required in order to keep inflation under control. The other challenge is to mobilize adequate revenue to finance prudent and equitable public expenditure and long-term investment. Clearly, overhauling both tax and expenditure systems is of the highest priority. This is not a straight task and will take several years of sustained effort. The interim government has started to reform both aspects. On the revenue side, it has rightly focused on overhauling the income tax system, where corruption is most endemic. The move to an online system is a smart policy step. But this alone will not yield the full benefits. Regarding expenditure management, a top priority is to cut back on fossil fuel subsidies and large infrastructure projects and increase spending on health, education, water resources and social protection. In the present environment of high inflation, higher spending on social protection with a focus on the poor is essential.

Public Enterprise Management: Loss-making public enterprises are draining the scarce fiscal resources of the Treasury with poor financial performance. Though public enterprises had assets valued at 16% of GDP in 2021, they claimed net fiscal transfers of 2-3% of GDP from the Treasury. This cannot go on. The core reforms involve corporate governance and pricing policy. This is a low-hanging fruit, which the Interim Government may want to focus on.

Investment Climate Overhaul: It is a pity that Bangladesh should receive FDI at barely 1% of GDP annually when even Myanmar and Pakistan receive higher FDI. Our investment climate needs to be overhauled to stimulate both domestic and foreign investment. Bangladesh’s restrictive trade policy discourages foreign investors who prefer economies with greater trade openness. So, besides ensuring robust infrastructure and uninterrupted power supply, trade policy reforms must be made a priority for attracting FDI.

The Imperative of Trade Policy Reform Now: This also presents an opportunity for rejuvenation of trade policy to foster robust growth. But it is also time for an overhaul of the governance and management of trade policy. Trade policy dualism, a scheme where RMG exports are subject to a different trade regime compared to all the rest, has run its course. It is time to articulate a unified trade strategy that fits the changing landscape of the 21st century global trade order. To begin with, the persistent case of anti-export bias of our trade policy needs to be reversed, and exports made more attractive than domestic sales.