This has almost become a ritual, not only for me but for many other Bangladeshi researchers

I have been writing religiously about the Bangladesh Annual National Budget since 2009. Either before the budget is announced, or after, or sometimes both.

This has almost become a ritual, not only for me but for many other Bangladeshi researchers.

Also ritualistically, the Ministry of Finance regularly invites me and other researchers to consultation meetings prior to the budget.

This is an excellent tradition in theory. But when it comes to the actual budget and its approval by the parliament, the outcome has been rather disappointing in most of the time.

In essence, the budget ends up as a heavily compromised, politically constrained document.

What has been more frustrating in recent years is the lack of realism in thetax revenue and expenditure targets of the budgets.

Over the past several years, the national budgets have set highly unrealistic tax revenue targets that have no bearing on what is feasible and also have little or no reform content.

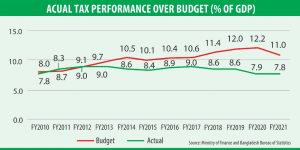

The end result, predictably, is a large gap between the budget target and the actual tax revenue performance that has been widening since FY2012 (Figure 1).

Distressingly, it also shows a progressive weakening of the tax performance.

And surprisingly, there is little debate in the cabinet or the parliament about this unrealistic budget making process and the need for reversing the poor tax performance with meaningful and reforms.

Source: Ministry of Finance and Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics

On the expenditure side, targets for spending on health, education, water management, and social protection are routinely missed owing to revenue constraint.

Consequently, as a share of GDP either these core spending are stuck at low levels or have fallen even further.

Thus, in FY2020 the actual spending on education was 1.9% of GDP; health spending was only 0.6% of GDP; spending on water resources was 0.7% of GDP, while spending on social protection (excluding civil service pensions), was a mere 0.9% of GDP.

Given this history, what can one really expect from the forthcoming national budget for FY2022?

I dare say, most likely it will be a repeat of past several years, with unrealistic revenue and spending targets that will not be achieved.

But I would optimistically like to be proven wrong.

Given the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic and the crunch in domestic economic activities, it would be unrealistic to expect major fiscal reforms in this FY2022 budget, even though they are long overdue.

But some element of fresh air can be induced in the budget.

As a start, the budget could come clean on the revenue situation. The Ministry of Finance should accept the ground reality on tax collection.

Instead of using bloated base year tax revenue figures for projecting the revenue target for FY2022, it should use the likely actual tax collection in FY2021.

The importance of this honest process to budgeting is illustrated by the experiences of tax performances in FY2020 and FY2021.

Actual tax collection in FY2020 stood at Tk220,800 crore as compared with a budget target of Tk340,100 crore, which is an outrageous shortfall of 54% that rendered meaningless the FY2020 expenditure targets.

In the FY2021 national budget, the tax target was similarly set at a ridiculously high level of Tk345,000 crore.

Tax revenue collected in the first 9 months until March 2021 was a mere Tk180,000 crore.

Applying the seasonality factor whereby revenue collections increase significantly in the last three months of the fiscal year, the estimated tax collection is likely to be about Tk242,800 crore, which is 10% higher than in FY2020 (as compared with actual collections that were only 6.4% higher during the first 9 months of the fiscal year.)

Once again, the likely revenue shortfall will be 42% over the budget target that similarly demonstrates the meaningless FY2021 tax and expenditure targets.

If the FY2022 budget uses the likely actual tax performance in FY2021 as the correct base for tax revenue projections, it can then set an optimistic tax revenue growth target of 15%, which will allow for a modest but meaningful increase in the tax to GDP ratio in FY2022.

This amounts to Tk279,200 crore, which is achievable even in the pandemic environment with some minimum tax reforms.

These reforms should focus on VAT and income taxes.

The VAT reform would entail implementing in a phased manner the actual 2012 VAT Reform Law.

For income taxes, modest improvements in tax collection can be brought about with such simple stroke-of-the-pen reforms like fully digitizing tax filing including online payments, removing the income-expenditure balancing requirement that discourages tax filing owing to fear of harassment, making audits highly selective and productive, fast-tracking the settlement of the backlog of tax cases, removing most tax exemptions, and bringing all sources of capital gains into the tax net.

Expenditure programming can then proceed on the basis of a realistic tax revenue base of Tk279,200 crore plus projected non-tax revenues plus resources from projected fiscal deficit. The non-tax revenue mobilization is a missed opportunity.

The government controls a huge volume of assets through investments in state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Barring profit transfers from a few SOEs like the telecoms sector (licensing fee), the BPC (in recent years), the Chittagong Port Authority, and the Bangladesh Bank (based on money creation), most SOEs are in deficit and require budget transfers to survive.

The government can turn around these enterprises to earn a positive rate of return on assets.

While the end result will take time, the process can start with this budget.

For the FY2022 Budget, the non-tax revenue target could be realistically set at around Taka 470 billion as defined in the 8FYP.

Regarding budget deficit, the actual fiscal deficit was 5.4% of GDP in FY2020.

The FY2021 national budget programmed a budget deficit of 5.9% of GDP, butactual deficit financing up to February 2021 indicates that the full fiscal year deficit will likely be lower at around 5% of GDP.

This suggests that the government wants to return to 5% of GDP deficit rule, although a case can be made for a somewhat higher deficit target to fight the COVID.

Using the ongoing inflation rate of 5.6% and estimated GDP growth of 6% (an optimistic assumption given the second COVID surge and associated lockdowns), projected nominal GDP growth for FY2021 is 11.9%, which amounts to an estimated GDP of Tk31,29,100 crore.

For FY2022, the 8FYP projects nominal GDP growth of 14% (8.2% GDP growth and 5.4 % inflation).

This appears too optimistic owing to the resurgence of COVID in 2021.

More realistically, GDP growth is not likely to exceed 6% in FY2022.

Applying that growth factor (11.7%), projected nominal GDP is Tk34,95,200 crore for FY2022. So, the projected fiscal deficit of 5% of GDP in FY2022 converts to resources of Tk174,800 crore.

Adding together, the total resource envelope for expenditure programming for the FY2022 Budget is Tk499,000 crore (Tk279,200 crore + Tk45,000 crore + Tk174,800 crore), which is 14.3% of GDP.

There are some fixed government obligations that take up a sizeable fiscal space.

These include mostly current spending on items like interest costs (2.1% of GDP), general services (1.1% of GDP), defense services (1.2% of GDP), and public order and safety (0.8% of GDP) .

So, allowing for these fixed spending, they leave some 9.1% of GDP for all other spending priorities.

Given the many priority spending needs, this indeed is a tough situation and presents an uphill battle to balance end with means.

Nevertheless, setting fictitious tax revenue target is self-defeating and realism and honesty in budget setting are a virtue.

They force the government to be strategic and careful in allocating resources.

Given the constrained revenue environment, a possible allocation pattern could be: education: 2.1% of GDP; health 0.8% of GDP; water resources 1.0% of GDP, social protection 1.2% of GDP, and others 4.0% of GDP.

Of the remaining 4.0%, the temptation would be to allocate most of it to infrastructure.

While infrastructure spending is indeed a priority, given resource constraint a good policy option would be to rebalance in favor of private sector financing.

Consequently, the allocation for transport, energy and power should not exceed 3% of GDP with an additional infrastructure financing of 1-1.2% of GDP coming from the private sector.

Fast tracking and reforming the PPP initiative is a high priority reform.

What is fundamentally important is that health, education, water, and social protection must receive higher budget allocation as a share of GDP in FY2022 as compared with actual spending during FY2020 and FY2021.

Protecting Bangladesh’s critical asset (human resources) is the most pressing challenge during these Covid infected times.

A full recovery to the 8% plus GDP growth rate path will not be possible without a recovery of the human capital lost during the Covid-19 pandemic.

And all out effort must be made to invest higher resources in human capital to restore the growth momentum.

The author is vice-chairman of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh