Reforms over the past two decades or so have greatly improved the quantity and quality of banking services in Bangladesh.

The urban areas are well served by a competitive banking sector with convenient access and a range of banking products, including electronic banking.

The rural areas are increasingly coming under the spread of commercial banking, supplemented by the large growth of microfinance institutions. A growing number of the unbanked rural population is being serviced through mobile financial services.

Interest rates are falling sharply and many borrowers with good track record are getting loans at single digit interest rate.

But, there is still a long way to go, especially to service the remaining large unbanked population and to meet the financing requirements of the host of micro and small enterprises that do not have access to banking sector credit.

Still, the above achievements are to be celebrated.

Policy effort should now seek to consolidate the gains and focus the banking sector agenda to achieve the country’s dream of securing the upper-middle income status by 2031. How well prepared is the sector to respond to this challenge?

Unfortunately, there are signs that some deep fault lines are emerging, which, if not addressed swiftly and with resolve, could create serious difficulties and hurt the country’s effort to move to the upper middle-income status.

These fault lines can broadly be grouped under two headings: the growing incidence of non-performing loans and the growing asset concentration among single borrowers.

International evidence suggests that both present high risks to the financial health and stability of the banking sector.

Indeed, the range of prudential norms underscored in the Basel rounds (Basel III now in place) is meant to guard against these and other systemic risks.

International evidence also shows the critical importance of having a highly professional and autonomous banking sector regulator, globally known as the central bank, to serve as the guardian of the banking sector health and to protect the depositors’ confidence in the banking system.

The lack of autonomy of the Bangladesh Bank is the third fault line that requires careful political debate and resolution.

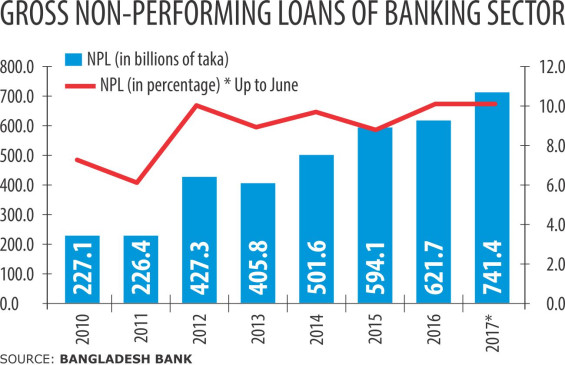

The amount of NPL climbed to an astounding Tk 70,400 crore ($8.8 billion) in fiscal 2016-17, which is 90 percent of Bangladesh’s actual annual development spending for the year.

While traditionally the NPL phenomenon is large in public banks for well-known governance problems, the evidence of rising NPLs in private banks presents additional challenges.

In a market economy, business-cycle related downturns can cause financial difficulties for private firms that could spill over to the banking sector. But there are many corrective instruments that the BB can use to manage these shocks.

What are near-impossible to tackle are difficulties infused in private banking by political interventions including constraints on the effectiveness of BB supervision.

One of the prudential instruments for portfolio management is the selection of bank board members based on the “fit and proper” test. There is a widely shared concern in the banking professional community that the quality of the boards in many private banks is weakening.

There is a growing dominance of non-professional private bank boards, often based on family connections and the BB has very little authority in practice to correct that.

As a result, lending decisions are not always made on solid business evidence but on connections. In this case, the risk to NPLs will obviously increase.

Furthermore, there is now a proposal under active consideration to further relax the prudential norm regarding board selection by increasing the tenure of board membership and allowing as many as four members of the same family to sit on the board.

Prudential norms usually limit the banking sector’s exposure to an individual and or family to a small number (usually to 10 percent) with a view to protecting the domino effect of the collapse of a business on the banking sector.

Global evidence of business collapses during an economic downturn is plenty. The most recent episode was the global financial crisis of 2008-2010 triggered by irresponsible lending and economic downturn in the US.

A large Bangladeshi business dealing with speculative commodity trading, stock market shares, or real estate transactions can easily go under, which could lead to its inability to service its bank loans. The larger the exposure of this firm, the larger the risk to the banking sector.

It is a no-brainer that the BB needs to protect the health of the banking sector against this risk by setting banking sector-wide exposure limits and closely monitoring its implementation.

Due to confidentiality, the BB does not publish the asset concentration data. But there is common talk in the banking profession that this asset concentration is growing, including through acquisition of several banks under single family ownership.

Whether or not it is true, the government and the BB would know best. If true, the BB needs to worry a lot and alert the highest level of policymaking about the associated risks and the possible reform options.

The degree of autonomy granted to a central bank is a contentious subject in most developing countries.

In advanced economies this is taken for granted and is an important indicator of good governance.

As Bangladesh aspires to attain upper middle-income status, it must also reform its institutions including the establishment of a professional and autonomous central bank.

If this principle is accepted, the government may want to re-examine the current management of the banking sector and strengthen the reach of the BB supervision to all banks along with full application of all prudential norms.

It must also refrain from any intervention in the functioning of the BB.

Bangladesh should be proud of its many achievements in the banking sector. It now needs to build on them and push ahead with banking reforms that will support the realisation of upper middle-income status by 2031.

Several deep fault lines have emerged that should be deftly managed to prevent backsliding on progress.

A combination of growing NPLs and asset concentration if unchecked can jeopardise the stability of the banking sector. Swift actions are needed to address these concerns.

The best solution is to increase the authority and autonomy of the BB to strengthen supervision of all banks (public and private) and apply the full prudential norms.