/ 28th Anniversary Issue-I

Challenges of sustainable post-Covid growth

On the 50th anniversary of its independence, Bangladesh stands, in many respects, as an exponent of development under democracy. Extreme poverty has declined by two-thirds from 44 per cent of the people in 1991, when Bangladesh restored democracy, to 14 per cent now. Primary education enrolment is almost universal with full gender parity. In critical indicators such as life expectancy (73 years for Bangladesh) and maternal and infant mortality, Bangladesh performs like a middle-income country, that is, better than not only neighbouring India and Pakistan but also than far more affluent Indonesia, the Philippines, or South Africa.

On the 50th anniversary of its independence, Bangladesh stands, in many respects, as an exponent of development under democracy. Extreme poverty has declined by two-thirds from 44 per cent of the people in 1991, when Bangladesh restored democracy, to 14 per cent now. Primary education enrolment is almost universal with full gender parity. In critical indicators such as life expectancy (73 years for Bangladesh) and maternal and infant mortality, Bangladesh performs like a middle-income country, that is, better than not only neighbouring India and Pakistan but also than far more affluent Indonesia, the Philippines, or South Africa.

Less well-known is that Bangladesh’s human development achievements overlie impressive and steadily accelerating growth rates. In the five years preceding Covid, GDP growth had exceeded 7 per cent on average, placing Bangladesh among five fastest-growing countries globally. The IMF’s latest estimates of this October projects our per- capita income to be $2,138 in current dollars and $5,733 in 2021 in internationally comparable PPP$, representing a more than six times increase in nominal terms and 3.5 times increase in real terms over the last 30 years. By this last measure, Bangladesh’s national income, at PPP$ 953 billion, makes it the 31st- largest economy globally, about the same size as Malaysia, South Africa, or the UAE.

Bangladesh’s growth has been resilient. While growth decelerated in 2020 and 2021 to 3.5 and 5.2 per cent respectively as part of the global economic reversal caused by the rampaging Covid-19 pandemic, it remained positive in Bangladesh in 2020 despite declining in 160 other countries and the world economy falling by 3 per cent.

If Covid beats a steady retreat in the face of effective vaccination campaigns, growth prospects for the world and Bangladesh will indeed be upside. Although most recent forecasts have turned cautious, analysts expect the global economy to bounce back in 2021, with growth rates recovering to 5 to 6 per cent. Unprecedented fiscal stimulus and increase in liquidity in the world’s biggest economies combined with pent-up demand from consumers and investors will boost global growth. In this context, international organizations project Bangladesh’s growth to recover to about 6.5 per cent in 2021-22.

The early data for leading indicators in Bangladesh in 2021 indeed suggest that recovery is underway. Industrial production, electricity use, exports and imports, and revenue collection have all rebounded. Moreover, as several mega-investment projects (the Padma bridge, the Dhaka light rail, the rail link and multiple-lane highways between Dhaka and Chattagram, and the tunnel underneath the Karnaphuli river to the port) come to completion, there should be a bump in growth. Recovery will partly depend on the state of the micro-and small- enterprise sector that had not benefited from government support to the same extent as the large-scale enterprises. Finally, it is worth emphasizing that Bangladesh’s success in containing Covid through an effective vaccination programme will also determine short-term economic recovery.

THE CHALLENGE OF SUSTAINING GROWTH: Despite optimistic recovery prospects in the near term, Bangladesh faces significant challenges to restore post-pandemic growth rates in line with the Eighth Five-Year Plan’s targets. These challenges will come from two sources: first, a changing and challenging international environment, and second, a substantial pending agenda to strengthen growth fundamentals that have become even more critical due to the first factor.

A Difficult International Environment: The October 2021 IMF assessment is global recovery may be more sluggish and “wobbly” than initially expected because of supply- chain bottlenecks. Because of trade disruptions last year, empty shipping containers are lying in ports of the world, without ships to carry them. Added to this, the shortage of port workers, sailors, and truck drivers, transport time and costs have sharply increased: the cost of shipping containers from East Asia to the US has quadrupled to $20,000 this year compared to a year ago. In manufacturing, a critical bottleneck is microchips, now used in a wide range of goods from computers, planes, trains, automobiles to toothbrushes. As factories shut down during the pandemic, an estimated two-year backlog of microchips and a shortage of a wide variety of manufacturing goods have emerged. These suggest that trade and exports, on which Bangladesh depends importantly, will likely be constrained in the near term.

A second reason for a sluggish recovery is rising political and economic uncertainty, especially in China and the United States, the world’s two largest economies that account for more than a third of global GDP. After decades of developing close trade, investment, and financial ties, a low-grade economic war in the form of tit-for-tat tariffs and restrictions on technology transfers is currently underway between the two powers, leading to a partial decoupling and economic disruptions. In the case of China, a key driver of growth, the real-estate sector is struggling under the burden of enormous debt; this, compounded by recent power shortages, led to a sharp deceleration of growth in the July-September quarter. In the case of the US, a fractious political divide is obstructing essential economic management such as passing the budget and even servicing debt. Furthermore, five million people are still out of work than before the pandemic struck. The European Union that accounts for nearly a fifth of the world economy is also facing difficult transitions. While the most prominent is Brexit, which is principally hurting Britain, there are other looming threats also. Germany, the largest economy and the regional hub, is also undergoing a significant political change as it forms a coalition government.

These international developments suggest that the world is now entering a period of considerable political and economic uncertainty. One reflection of this is that growth forecasts have been pared back across the board in East Asia, the fastest-growing region globally for several decades.

In addition to these overall adverse trends, Bangladesh faces the specific challenge of graduating under UN procedures from a least- developed economy to a developing economy in 2024. After a grace period, Bangladesh’s economic prospects will confront a decline in international support measures such as duty-free and quota-free access, preferential rules of origin, and waivers from intellectual property rules. Access to the EU, Canada, Japan, and other markets — major markets — will become more competitive.

Benchmarking Bangladesh on Growth Fundamentals: There is only one overall policy response to these challenges: making the economy more diversified, competitive, and productive through policy and institutional reforms that bring about structural change and boost physical and human capital investments. As the 2021 UNCTAD report on least-developed economies has stressed, Bangladesh will need “A concerted push towards patterns of specialization with higher levels of complexity, and where knowledge and technological spillovers are higher.”

How will Bangladesh make this concerted push? To use Nobel- laureate economist Robert Lucas’s terminology, “the mechanics of economic development” is a product of a few key variables: human and physical capital and, more important in the long run, and their productivity. Achieving these requires savings and investment by governments, large and small firms, farms, and households. Crucially, investments must occur not only in physical stock but also in education, knowledge, institutions, good governance, and the financial sector. The last will encourage savings and efficiently allocate them to productive investment. Finally, long-run growth will need economies of scale and agglomeration provided by urban development and international trade and investment. These variables are the growth fundamentals on which Bangladesh will need to focus.

Providing these growth fundamentals is not easy. That is why less than 20 middle-income countries have completed the journey to become high-income country in the last 60 years while others have fallen into the “middle-income trap”. Where does Bangladesh stand in providing these fundamentals?

We will answer this question by seeing how Bangladesh compares now to three selected countries or country groups when they were at similar income levels. Specifically, we will use Bangladesh’s pre-Covid year per-capita income of PPP$ 4,754in 2019, i.e., in dollars measured by internationally comparable purchasing-power parity in constant prices of 2017 to identify the state of our comparators at a similar income. As multiple issues will be identified, we will be listing them without going into details.

Our comparator countries and country groups are all in Asia:(i) neighbouring India, (ii)Vietnam, and (iii) Developing East Asia (that exclude high-income countries). We will ask how these countries provided these fundamentals when they had similar per-capita incomes: 2014 for India, 2009 for Vietnam, and 2003 for developing East Asia.

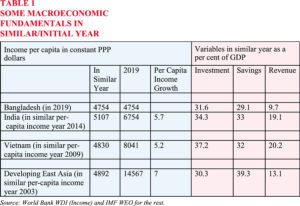

These comparators were chosen for two reasons: first, they are in our region with reasonably similar characteristics of geography, small-scale agriculture, and large populations. Second, because they represent the most dynamic economies in recent decades. In the last five years before Covid, developing East Asia accounted for 40 per cent of global growth. Further, as Table 1 shows, in the 13 years between 2003 and 2019, developing Asia tripled its per-capita income while India and Vietnam’s per-capita income grew more than 5 per cent between their initial year and 2019, like recent Bangladesh’s growth over the last decade.

These comparators were chosen for two reasons: first, they are in our region with reasonably similar characteristics of geography, small-scale agriculture, and large populations. Second, because they represent the most dynamic economies in recent decades. In the last five years before Covid, developing East Asia accounted for 40 per cent of global growth. Further, as Table 1 shows, in the 13 years between 2003 and 2019, developing Asia tripled its per-capita income while India and Vietnam’s per-capita income grew more than 5 per cent between their initial year and 2019, like recent Bangladesh’s growth over the last decade.

One objection could be these countries are culturally, politically and by economic systems heterogeneous, different from Bangladesh, and thus not comparable. That, however, is not relevant here as we will focus on growth fundamentals. Regardless of cultures, societies, and systems, all economies must deliver on these fundamental variables to sustain high growth. Society, culture, politics, and economic management will influence how a country provides these fundamentals but deliver they must for rapid growth.

The first set of results for macroeconomic fundamentals in Table 1 are clear, even if not particularly surprising, as quite a bit has been written about them. To start with, in 2019, Bangladesh performs well in investment compared to the developing East Asian average when they had similar per-capita incomes in 2003 (last row). But compared to India and Vietnam our investment lags markedly behind. Thus, we need to improve our investment climate to increase our investment rate

The gap is larger in savings. The implication is that our financial sector will need a major overhaul to become more efficient in boosting savings and allocating them efficiently. This is a major task to which we will return. The other important takeaway from Table 1 is that Bangladesh significantly lags – by between 6 and 10 percentage points of GDP – in revenue collection and, thereby, in expenditures on critical public goods and services. Much has been written about these issues, including by myself.

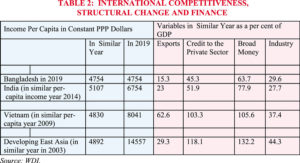

The second set of results presented in Table 2 discusses trade competitiveness, industry, and finance, all areas where Bangladesh needs significant catch-up with comparators. Consider first the case of exports and imports in the share of GDP. While not without flaws, these variables suggest how globally competitive an economy is.

The second set of results presented in Table 2 discusses trade competitiveness, industry, and finance, all areas where Bangladesh needs significant catch-up with comparators. Consider first the case of exports and imports in the share of GDP. While not without flaws, these variables suggest how globally competitive an economy is.

The first salient point is comparators’ economies had dramatically higher shares of exports at about the same per-capita income of Bangladesh in 2019. Historically, trade has been essential for growth because it provides economies of scale, technology, and incentives to be competitive. Thus, even more concerning is that Bangladesh’s exports in percentage of GDP is not only low, but it has declined from a peak of 20 per cent in 2012. In Vietnam, the opposite happened: exports’ share increased from 62 per cent in 2009 to 106 per cent now.

The second finding is that both Bangladesh and India also dramatically lag in financial depth measured by the share of broad money and credit to the private sector in GDP. As it happens, in Vietnam by 2019, private sector credit has increased further to 133 per cent of GDP.

Consistent with these findings, Bangladesh and India also lag in industrialization – i.e., manufacturing, construction, and utilities – by about 10 percentage points in industry’s share in the economy compared to Vietnam and developing East Asia average. Unless this gap in industry share narrows, the prospects for both employment and productivity growth will be dim.

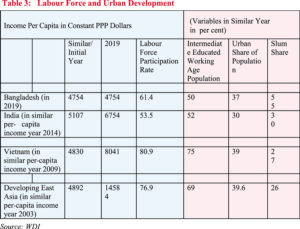

Labour Force and Urban Development: Our last set of results focus on two other drivers of growth: labour force and urban development. Both theory and data suggest that fast-growing countries properly educate and employ their labour force. Second, rapid growth requires the development of cities and towns where industries and services benefit from economies of scale and agglomeration.

The findings of our exercise in Table 3 need careful interpretation. In labour-force participation and education, both India and Bangladesh lag markedly behind. While Bangladesh’s labour-force participation ratio at 61 per cent is significantly higher than India’s thanks to the higher participation of Bangladeshi women in the workforce, they are lower than in developing East Asia. Again, the reason is much higher female labour force participation in East Asia. On education, too, developing Asia and Vietnam were far more advanced than Bangladesh at a similar income level: nearly 80 per cent of the working-age population participated in the labour force, and 70 per cent or more of the workers had intermediate-level education.

The findings of our exercise in Table 3 need careful interpretation. In labour-force participation and education, both India and Bangladesh lag markedly behind. While Bangladesh’s labour-force participation ratio at 61 per cent is significantly higher than India’s thanks to the higher participation of Bangladeshi women in the workforce, they are lower than in developing East Asia. Again, the reason is much higher female labour force participation in East Asia. On education, too, developing Asia and Vietnam were far more advanced than Bangladesh at a similar income level: nearly 80 per cent of the working-age population participated in the labour force, and 70 per cent or more of the workers had intermediate-level education.

Urban development presents a more complicated picture. Bangladesh’s urban population share is higher than what India’s was in 2014. Vietnam in 2006 had a lower urban-population share, which rapidly increased in the last 15 years to match Bangladesh. Developing East Asia overall, however, had a significantly higher urban population share in 2003. In the case of Bangladesh, the high percentage of the urban population living in slums dampens Bangladesh’s performance in urban development. That takes us to the next point below.

It is Not Only Quantity – But also Quality that matters.

So far, following the mechanics of growth, we discussed a dozen growth fundamentals where Bangladesh quantitatively lags high-performing East Asian developing countries and Vietnam at similar income levels. In closing, we will summarize the seven critical lessons for sustaining growth that our exercise has suggested. In doing so, we will go one step further to stress that it is not only quantity but also quality that matters.

First, Bangladesh’s investment rate will need to increase by four to five percentage points of GDP. Moreover, the quality of investment must also be high. In the case of public investment, proper project selection, minimizing cost and time overruns, and slowing depreciation through appropriate maintenance will be essential. Otherwise, simply increasing spending will not deliver the rapid growth we need. More broadly, the bulk of the increase needs to come from private investment, which stalled in the last few years. Further, private investment should come without distortionary or costly incentives provided by tariff and tax privileges or high-priced guarantees.

Second, it will be critical to attract foreign direct investment not only for its financing but also for its technological expertise and linkages to supply chains and foreign markets. It is implausible that Bangladesh will diversify its exports and upgrade its technology to become globally competitive without FDI. All the fast-growing countries of developing East Asia have benefited from large volumes of FDI.

Third, as widely discussed in our national dialogue, Bangladesh needs to increase its revenue effort significantly. East Asian countries’ revenue-collection effort at Bangladesh’s present income level was twice that of Bangladesh. Expenditure allocation will also need scrutiny to avoid unproductive expenditures such as subsidies and investment guarantees that deprive other needed public services for the people.

Fourth, Bangladesh significantly lags in export competitiveness and diversification compared to East Asian economies at similar income levels. As just noted above, the role of FDI will be key here. But complementary to that will be the need to remove the deep anti-export biases in our policies: high rates of import protection through tariffs and tax holidays and real effective exchange rate appreciation by close to 50 per cent in the last seven years. Monetary policy measures will need to counteract the appreciating impact of high remittance flows on our exchange rate. Developing East Asian economies were famous for using a slightly undervalued exchange rate to stay competitive.

Fifth, as seen earlier, Bangladesh and its neighbour India dramatically lag in financial deepening, including providing credit to the private sector. This lag is partly the result of dampened private investment and the high share of non-performing loans that have clogged credit flows. Addressing these challenges will be critical because higher investment rates will not be possible without mobilizing savings and allocating them efficiently through credit.

Sixth, urban development is another area where Bangladesh follows behind the high-performing East Asian regions. While the share of urban population is high, half of that population live in slums. This is consistent with other research that suggests the dynamism of urban economies is faltering. They are not creating enough firms and good urban jobs, thereby stalling urban poverty decline and real wage growth.

Last, but not the least, Bangladesh lags significantly behind East Asian countries when they were at our stage of development in employing and educating its working-age population. In fact, in education, the data we have discussed markedly understates the problem. It only highlights that barely half of the labour force has post-secondary education. It does not discuss the dismal quality and competency findings of National Student Assessments due to the inferior quality of education. Nor does it discuss structural problems such as inadequate attention to providing technical and vocational education for workers. In both these areas, East Asian economies performed much better.

Our Eighth Five-Year Plan recognizes these critical issues. As it happens, the plan targets the fundamentals identified by our exercise for achieving in the final year fiscal 2024-25. The difference is that high-performing East Asian economies had already attained these targets when they were at the same per-capita income level as we had in 2019. We have urgent catching up ahead.

Bangladesh has important strengths. . Our population is young, and if educated and trained well, we can benefit from a demographic dividend. The economy rests on a sound agricultural sector that has considerable scope to diversify and boost growth. Thanks to the recent significant rise in public investment, our infrastructure – electricity and transport – is being rapidly upgraded. Power supply is abundant and with improvements in the grid that should attract investment, both domestic and foreign. More than two-thirds of the population are literate and the physical facilities for education from elementary to higher education are now available widely. Mobile telephony penetration has now reached more than 90 per cent of the population. In general, there is a spirit of entrepreneurship in the economy, an experienced investor class and workforce, and the confidence of a history of growth and human development.

What we now need are good policies and institutions that will provide the incentives to invest in and use these resources to meet Bangladesh’s challenges.

Dr Ahmad Ahsan is Director, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh and previously a World Bank economist and Dhaka University faculty member. All views expressed here are personal.

He can be reached at ahmad.ahsan@caa.columbia.edu

https://today.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/28th-anniversary-issue-1/lessons-from-fast-growing-neighbours-1636453253