Bangladesh showed strong resilience and dynamism by rising rapidly from the ruins of a war-devasted economy in 1972 that was characterized by high incidence of poverty (around 80%), low per capita income (less than $100) and badly damaged infrastructure. In 2015 Bangladesh crossed the threshold of the World Bank-defined lower middle country (LMIC). In FY2019, per capita income stood at $1909 and poverty rate was estimated at around 22%. Buoyed by these accomplishments, Bangladesh now aspires to achieve upper middle-income country (UMIC) status and eliminate extreme poverty by FY2031. The target GDP growth rate from FY2019-FY2031 is projected at around 8-9% per year.

Bangladesh showed strong resilience and dynamism by rising rapidly from the ruins of a war-devasted economy in 1972 that was characterized by high incidence of poverty (around 80%), low per capita income (less than $100) and badly damaged infrastructure. In 2015 Bangladesh crossed the threshold of the World Bank-defined lower middle country (LMIC). In FY2019, per capita income stood at $1909 and poverty rate was estimated at around 22%. Buoyed by these accomplishments, Bangladesh now aspires to achieve upper middle-income country (UMIC) status and eliminate extreme poverty by FY2031. The target GDP growth rate from FY2019-FY2031 is projected at around 8-9% per year.

There are many reforms that will need to underpin this transition from LMIC to UMIC. The development strategy and associated policy and institutional reforms for UMIC, and eventually to reach high-income country (HIC) by FY2041, have been worked out in some detail in the government’s Perspective Plan 2041(PP2041). This article focuses on the key elements of what will constitute a proper fiscal policy for UMIC Bangladesh.

Core fiscal policy principles for upper middle-income status

Based on good practice and international experience, there are certain core principles that would guide the formulation of a good fiscal policy for Bangladesh. These principles say: (1) support macroeconomic stability; (2) make the budget growth-oriented; (3) develop a redistributive fiscal policy to reduce income inequality; (4) establish a productive, efficient and equitable tax system; (5) reform public enterprises to maintain long-term fiscal solvency and avoid misuse of public resources; and (6) promote fiscal decentralization.

The underlying rationale for these policies is easy to see. A stable macroeconomic environment, defined as exhibiting low inflation, low real interest rate, a stable nominal exchange rate and low public debt, is a major enabler of the expansion of private investment and GDP growth. Macroeconomic stability helps keep real interest rates low, allows long-term investments to be made by reducing uncertainty about movements of prices and exchange rate and helps create fiscal space for essential spending instead of debt servicing. Public expenditures can similarly be a major boost to private investment and GDP growth by supporting the development of infrastructure and human capital. Evidence from several OECD countries show how redistributive fiscal policies combining progressive income taxation with proper social spending can lower income inequality.

For these three outcomes to happen, a critical requirement is to institute a taxation structure and a tax policy that are productive in terms of revenue yield, efficient in terms of minimizing the adverse effects of taxation on private investment and labor supply, and equitable in terms of having progressive tax incidence. The fifth principle concerning the financial health of public enterprises gets prominence in the context of Bangladesh because there is a sizable public enterprise sector that is a drag on government resources, requiring frequent and large budget transfers to stay afloat. Without proper reform of this ailing public enterprise sector, the transition to UMIC will become very difficult.

Finally, successful UMIC and HIC are all characterized by a system of well-functioning decentralized local governments that are financially autonomous, capable of raising considerable resources on their own and providing efficient basic services to residents in the areas of health, education, water supply, sanitation, and environmental services. Indeed, without an efficient and autonomous system of local governments, the growing social cost of the present haphazard urbanization will become a huge constraint on Bangladesh development.

Supporting macroeconomic stability

International evidence suggests that sustained 8-9% annual GDP growth will require an average investment equivalent to about 36-39% of GDP. This compares with an investment rate of about 31% of GDP in FY2019 (23% for private sector and 8% for public sector). The PP2041 projections suggest that the private investment rate should grow from 23% to an average rate of 28% during FY2021-FY2031. This is huge policy challenge, especially because the average private investment during the 7th Five Year Plan has remained virtually stagnant at 23% of GDP.

Many policies will be needed to achieve this large expansion of private investment. On the fiscal policy front, a key requirement is to maintain fiscal stability by keeping public domestic borrowing under control. Fiscal projections in the PP2041 macroeconomic framework suggest that this entails a budget deficit of around 5% of GDP. Monetary policy that is consistent with the 5% long-term inflation target will then be able to adequately balance the private credit needs with public bank borrowing requirements.

Larger fiscal deficits financed by bank borrowing will likely either crowd out private credit or require higher liquidity growth that will be inconsistent with the long-term inflation target. Higher inflation in turn can cause numerous problems for macroeconomic stability including exchange rate instability, balance of payments pressure, and pressure on domestic interest rates. High fiscal deficits can also cause a ballooning in public debt that could create dynamic fiscal instability through rising interest cost, thereby constraining fiscal space for growth-oriented spending.

The past track record of Bangladesh in maintaining fiscal prudency is good. The budget deficit on average has been contained at or below 5% of GDP, which has helped the Debt to GDP ratio to decline from its peak of around 50% to a relatively low level of 30% of GDP. However, there have been important changes in the debt-financing environment that could impose financial stress on the budget unless well managed. Fiscal deficits are increasingly financed with high-cost domestic instruments such as national savings certificate. The average cost of foreign financing is also rising. These have contributed to the growing interest cost of public debt. Bangladesh, therefore, needs to carefully watch the cost of debt financing even as it limits the size of the fiscal deficit to around 5% of GDP. The adoption of a well-thought deficit financing strategy is an important reform for UMIC Bangladesh.

Making budget growth oriented

In addition to macroeconomic stability, a prudent fiscal policy does support growth in two major ways: (a) it boosts public investment; and (b) provide incentives for private investment.

Financing infrastructure: The PP2041 projections suggest that public investment needs to expand by an average of about 3 percentage points of GDP to support the GDP growth target of 8-9% per year (up from the average rate of 7% during the 7th FYP to 10% of GDP over FY2021-FY2031). Much of this additional investment will need to go for upgrading the physical infrastructure (power, energy, transport, flood control and irrigation) to support GDP growth. Past investments in infrastructure, especial

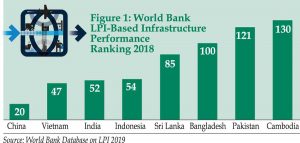

ly the development of the power sector, has been a major contributor to GDP growth during the FY2010-FY2019 periods. Yet, a substantial infrastructure gap remains. Investors continue to identify infrastructure as a major constraint to domestic and foreign investment. While Bangladesh has improved its infrastructure services in recent years and outperforms competitors like Cambodia and Pakistan, it is way behind more dynamic and competitive countries like China, Indonesia, Vietnam and India (Figure 1). The investment requirements for better infrastructure services are large. Furthermore, there are many performance issues relating to quality and cost of infrastructure service delivery that will need to be addressed.

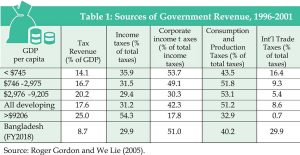

Tax and subsidy policy implications for private sector incentives: Tax and subsidy policies can affect private investments through incentives. These effects can often be unintended consequences of the taxation system. In Bangladesh, the unintended consequences of the taxation system on resource allocation is substantial and generally not supportive of efficiency of private investment or GDP growth. Bangladesh relies heavily on trade taxation relative to other countries, both low-income and middle income (Table 1). This has severe negative effects on exports, while boosting inefficient import substitution. While Bangladesh provides a number of fiscal incentives to support exports including bonded warehouse scheme, duty drawback scheme and direct export subsidies, they mostly help RMG but no other exports. So, the reform of tariff and para-tariff policies with a view to eliminating the anti-export bias of the fiscal policy is a critical need. This is necessary to enable Bangladesh to move on to the UMIC path.

Tax and subsidy policy implications for private sector incentives: Tax and subsidy policies can affect private investments through incentives. These effects can often be unintended consequences of the taxation system. In Bangladesh, the unintended consequences of the taxation system on resource allocation is substantial and generally not supportive of efficiency of private investment or GDP growth. Bangladesh relies heavily on trade taxation relative to other countries, both low-income and middle income (Table 1). This has severe negative effects on exports, while boosting inefficient import substitution. While Bangladesh provides a number of fiscal incentives to support exports including bonded warehouse scheme, duty drawback scheme and direct export subsidies, they mostly help RMG but no other exports. So, the reform of tariff and para-tariff policies with a view to eliminating the anti-export bias of the fiscal policy is a critical need. This is necessary to enable Bangladesh to move on to the UMIC path.

More importantly, the entire taxation policy and system of fiscal incentives need to be revisited and corrected where ever necessary through a careful review of their effects on the quantity and quality of private investments. For example, the highly favorable tax treatment of capital gains from land and property transactions tends to divert resources from manufacturing and other private enterprises to land and property transactions, many of which are speculative in nature. Another example is the heavy taxation of the information communications technology (ICT) sector that militates against new investment and growth of this high-development impact sector.

More importantly, the entire taxation policy and system of fiscal incentives need to be revisited and corrected where ever necessary through a careful review of their effects on the quantity and quality of private investments. For example, the highly favorable tax treatment of capital gains from land and property transactions tends to divert resources from manufacturing and other private enterprises to land and property transactions, many of which are speculative in nature. Another example is the heavy taxation of the information communications technology (ICT) sector that militates against new investment and growth of this high-development impact sector.

Redistributive fiscal policy to lower income inequality

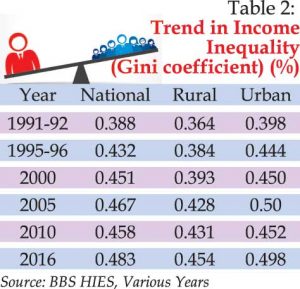

Along with higher growth and poverty reduction, Bangladesh has experienced a serious long-term rise in income inequality (Table 2). The UMIC Bangladesh must tackle this forcefully to establish a more caring society and avoid fanning social instability down the line. Positive experience gained from Western Europe, Canada and Japan does suggest that there is no necessary trade-off between GDP growth and income distribution, and a redistributive fiscal policy can play a major role in tackling income inequality as income grows. This essentially involves the institution of a progressive income tax regime based on the principle of ability to pay, combined with adequate spending on core social programs including health, education and social protection.

On the taxation front, a major weakness of the tax structure is the absence of a progressive personal income taxation. Bangladesh presently secures a mere 1.3% of GDP from personal income taxation, which is among the lowest in the world. Although in paper, Bangladesh has instituted a progressive system of personal income taxes, compliance is very poor. There are several reasons for that including a complex tax structure, weak tax administration and corruption.

On the taxation front, a major weakness of the tax structure is the absence of a progressive personal income taxation. Bangladesh presently secures a mere 1.3% of GDP from personal income taxation, which is among the lowest in the world. Although in paper, Bangladesh has instituted a progressive system of personal income taxes, compliance is very poor. There are several reasons for that including a complex tax structure, weak tax administration and corruption.

On the expenditure side, a major issue is that the extremely tight fiscal space owing to low tax revenues severely limits the government’s ability to increase critical spending on the social sector. The spending gaps on social sector between Bangladesh and selected middle income / high-income countries is yawningly large. As an example, public spending in Bangladesh is 1.8% of GDP on education, 0.7% on health and 1.5% on social security (excluding civil service pensions). This compares very unfavorably with public education spending of 5-7% of GDP (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, South Africa, France, Germany, UK, Denmark, Norway and Sweden); health spending of 4-9% of GDP (Argentina, Brazil, South Africa, Canada, France, Germany, UK, Denmark, Norway and Sweden); and social security spending of 6-18% of GDP ( Chile, Colombia, South Africa, France, Germany, UK, Norway and Sweden).

On the expenditure side, a major issue is that the extremely tight fiscal space owing to low tax revenues severely limits the government’s ability to increase critical spending on the social sector. The spending gaps on social sector between Bangladesh and selected middle income / high-income countries is yawningly large. As an example, public spending in Bangladesh is 1.8% of GDP on education, 0.7% on health and 1.5% on social security (excluding civil service pensions). This compares very unfavorably with public education spending of 5-7% of GDP (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, South Africa, France, Germany, UK, Denmark, Norway and Sweden); health spending of 4-9% of GDP (Argentina, Brazil, South Africa, Canada, France, Germany, UK, Denmark, Norway and Sweden); and social security spending of 6-18% of GDP ( Chile, Colombia, South Africa, France, Germany, UK, Norway and Sweden).

Moving forward, amongst the highest priority for fiscal policy for UMIC Bangladesh is to substantially increase public spending on education and training. Public investment in education and training is a critical policy to increase the earnings potential of the poor and low-income group. Additionally, the skills base of a middle-income Bangladesh will be vastly different from the present level where, as shown by the labor force survey of 2017, some 32% of the workforce did not have any education, 26% had only primary education, 31% had secondary education and only 12% had tertiary and higher education. This education profile of the labor force is inconsistent with the needs of a UMIC Bangladesh.

Moving forward, amongst the highest priority for fiscal policy for UMIC Bangladesh is to substantially increase public spending on education and training. Public investment in education and training is a critical policy to increase the earnings potential of the poor and low-income group. Additionally, the skills base of a middle-income Bangladesh will be vastly different from the present level where, as shown by the labor force survey of 2017, some 32% of the workforce did not have any education, 26% had only primary education, 31% had secondary education and only 12% had tertiary and higher education. This education profile of the labor force is inconsistent with the needs of a UMIC Bangladesh.

A minimum of 12 years of compulsory education for all children combined with an effective adult literacy programme and specialized skills training to meet the skills requirement of a UMIC Bangladesh in the global environment of the 4th Industrial Revolution (IR4) will be necessary. An additional budget spending by at least 1.7-2% of GDP per year over the next 5-10 years is essential to develop the education and skills base for middle-income Bangladesh. This additional investment will also help reduce income inequality by building up human capital of the poor and reducing the skills gap between the rich and the poor.

Along with education, public spending also needs to grow in health, nutrition and social protection. Although Bangladesh has secured major improvements in health and nutrition outcomes with limited public health spending, this has been partly possible because of adoption of low-cost solutions and eradication of many mass-communicable diseases. With the changing demographic pattern and the growing incidence of complex diseases, this limited public spending will not be able to meet the public health requirements of a middle-income society.

Although healthcare is primarily funded out of pocket, there is a serious equity issue in view of the absence of health insurance system. Bangladesh needs to make a concerted effort to introduce health insurance schemes, with private sector schemes for the upper income group but public low-cost subsidized schemes for the poor and low-income groups. Public investments in curative health care programmes for the poor and low-income group will be necessary. Funding for health research and health care staff education and training will also need to increase. All these will require additional public spending in health sector. For UMIC Bangladesh, public health spending needs to go up from 0.7% of GDP to at least 1.5% of GDP by FY2025 and maintained at that level until FY2031.

Bangladesh traditionally has been conscious of the need for a strong social protection programme in view of the extreme vulnerability of the population to poverty, climate change and natural disasters. A multiplicity of social safety net schemes has emerged over the years, supported by increasing government funding and donor-supported schemes. This free-for-all approach however has created an uncoordinated and complex system of a large number of safety net schemes that yields very low average benefits. The system is also inefficient and involves high delivery cost along with leakages.

In response, the Government adopted a modern system of social protection programme (called the National Social Security System or the NSSS) that seeks to consolidate the large number of low-benefit schemes into a few substantial programmes built around meeting the needs of the life cycle vulnerabilities. The NSSS proposes major institutional reforms to consolidate the various schemes and move towards a cash-based system based on proper identification of the eligible beneficiaries and on-line transfers through mobile financial services or banking networks. Additionally, it calls for establishment of a national pension scheme for both public and private sectors.

The NSSS is a big reform and its full implementation will provide a major boost to social protection in Bangladesh. Unfortunately, implementation has been very slow and piece meal. The major institutional reforms have not happened. And the large number of safety net schemes continue to exist. On top, budgetary constraint owing to the narrowing of the fiscal space is creating a financing challenge for social protection. In the context of attaining UMIC status, the rapid implementation of the NSSS and associated institutional reforms are other top priority fiscal reforms. The social security budget must increase from the present 1.5% to at least 3% by FY2025 and maintained at that level until UMIC status is achieved by FY2031.

Towards a productive, efficient and equitable tax system

The ability to secure the objectives underlying the first three principles discussed in Sections C, D and E is contingent upon the institution of a major overhaul of the tax system. Notwithstanding recent reforms, the tax regime in Bangladesh is quite primitive and suffers from low productivity, low efficiency and is inequitable. The tax to GDP ratio has grown very slowly and is hovering around 9% of GDP. The tax structure is heavily reliant on trade and consumption taxes with low yield from income taxes. Personal income taxes yield a mere 1.3% of GDP despite a heavy concentration of income among the top 5-10% of the population. Corporate tax rates are highly discriminatory in nature with incentives for RMG, land and stock holdings but high penalty rates for others including banking and ICT. Trade taxes provide heavy protection to import substitutes and penalize exports.

A thorough overhaul of the tax system is needed to meet the development objectives of middle-income Bangladesh. The objectives of this reform should be: first, to increase the tax to GDP ratio along the lines indicated in the macroeconomic framework of PP2041; secondly, to improve the efficiency of the tax regime by carefully reviewing and reforming the incentive effects of the same and implications for private investment; and thirdly, to improve the equity of the tax system by instituting a progressive income tax mechanism that is based on the ability to pay principle. The tax administration and planning need to be modernized with particular objectives to strengthen tax planning, to simplify tax collection using electronic transactions and simple information, and to avoid the harassment of citizens.

The tax revenue mobilization challenge: The public resource mobilization task underlying the Macroeconomic Framework of PP2041 is particularly challenging in that it seeks to raise total revenues as a share of GDP from 10% in FY2018 to 20% by FY2031 and tax revenues from 8.7% to 17.4% over the same periods. These amount to a near doubling of the tax and total revenue mobilization efforts over a period of 12 years. The ability to achieve the tax target will determine the success with the total revenue mobilization effort.

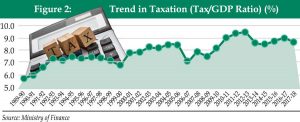

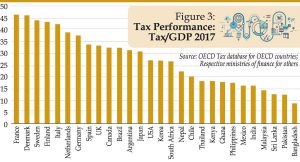

As against these ambitious targets, the tax performance in recent years is summarized in Figure 2. The tax/GDP ratio has grown modestly over the past 28 years (3 percentage points on aggregate). In more recent years (FY2010-FY2018), the tax to GDP ratio has basically stagnated, fluctuating around 9% of GDP. This is the lowest tax performance in South Asia and among the lowest in the world (Figure 3). Clearly, the PP2041 tax and revenue targets are overwhelmingly large in relation to the actual performance so far.

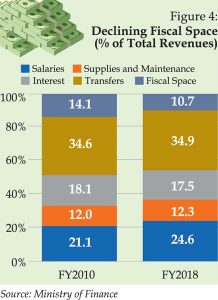

One major consequence of this low tax effort is the increasingly constrained fiscal space. Fixed obligations like civil service salaries, defense spending, office supplies and materials, interest cost of public debt and transfers are increasingly eating up the low level of available revenue resources, leaving little space for development spending needed to support GDP growth and human development (Figure 4).

Tax equity challenge: High- income countries on average raise about 16% of GDP as personal income taxes, accounting for about 50% of total tax revenues. As compared to this, low-income countries collect about 2.3% of GDP and low-middle income countries mobilize 2.7% of GDP. Bangladesh collects a mere 1.3% of GDP as personal income taxes (FY2018) and this ratio has grown only marginally (it was 1% of GDP in FY2010) even as per capita income more than doubled over the past eight years.

In addition to numerous legal exemptions, at the heart of the personal income taxation problem is the low level of compliance. The estimated compliance rate is a mere 12%. Owing to exemptions and low tax compliance, actual tax yield from personal income has grown slowly, from a low yield of 0.41% of GDP in FY2000 to about 1% of GDP in FY2018. As compared to this low revenue yield, depending upon the level of income the legal tax rates vary from 10% to 30% plus.

The potential loss of revenue from exemptions and low compliance is illustrated in Table 3 under two scenarios. The first scenario assumes an effective average tax rate of 10% on the income share of the top 10 percentile. This group has average income much higher than the tax exempted level of Taka 2,50,000. The second scenario is a bit more ambitious and involves an effective average tax rate of 15% on the income share of the top 10 percentile. With proper reforms of the income tax that does not require any increase in tax rates but better implementation, including a move towards the concept of a universal income tax base with minimum exemptions and an effective tax administration mechanism, the yield from personal income tax could reach 3.8% of GDP under Scenario 1 and 5.7% of GDP under Scenario 2. Compared to these personal income tax potential scenarios, the very low actual yield dramatically illustrates the very low productivity of the personal income tax system.

Tax evasion is particularly large at the highest levels of income. A range of factors explain this tax evasion problem including legal tax exemptions and loopholes, political connections, corrupt practices, complexities of tax assessment and collection, inefficient tax audits and high marginal rates of taxation. Reform efforts have focused on enlarging the tax base by bringing more tax payers in the tax base through electronic tax IDs, cross checks on bank accounts, utility bills, home rentals, tax exhibitions, import transactions, etc. To improve the productivity of audits, a Large Tax Payer Unit (LTU) has also been established to monitor tax returns of large payers. These reform efforts have yielded some results. The number of registered personal income tax payers has increased noticeably but the average nominal yield per tax-payer has been erratic with no discernable pattern. The average return per taxpayer has fallen when accounting for inflation.

Thus, while the effort to bring in more people in the income tax net is laudable, the productivity in terms of impact on revenue yields has been small. The stagnant or declining nominal yield per taxpayer suggests that tax returns are not able to capture the tax benefits of the growth of personal income at a time where the economy is highly buoyant and there is evidence of a growing concentration of personal income from HIES data. This possibly reflects the effects of serious tax evasion and the inability to get the big income earners in the tax net.

Inefficiencies of the tax system: Two serious problems with the tax system in Bangladesh is the complexity of the tax laws and collection process and the harassment of the tax payer. Tax filing is not user-friendly, simple or automated. One example of a bad feature of the present tax design that discourages tax filing and leads to harassment and corruption is the requirement to file a wealth statement based on balancing of income and expenditure along with the tax return. Many tax payers find this requirement onerous and it discourages them from filing taxes because of the fear that this will lead them to various forms of harassment. This also encroaches on the privacy of a citizen. While the government has the right to tax the income, it is debatable whether citizens should be required to explain how they spend their money.

The value of this dubious requirement in terms of tax collection is negligible and on a net basis negative because it discourages tax filing. More importantly, there is a common perception that this feature creates incentives for income tax officers to harass tax payers and extract a bribe. So, despite this intrusive tax policy, the returns from personal income taxes as a share of GDP has hardly grown over the past 8 years even with a doubling of per capita income in dollar terms. It is obvious that the wealth and income-expenditure statements have not helped increase revenues but have tended to support revenue leakages through non-filing and collusion between taxpayers and tax collectors

Similar problems exist as for corporate income taxes. For registered firms, the compliance rate is only 21%. The corporate tax rates vary considerably by activities. There is a zero rate for many sectors or activities that are either exempted from taxes or are given tax holidays for a number of years. Positive rates range from a low of 15% to a high of 45%. The NBR has targeted a few cash cows and slapped them with high tax rates: Tobacco (45%); mobile telephone companies (40%); and banks and insurance companies (40-42.5%). There is very little analysis to understand the implications of the existing corporate tax structure on incentives including for foreign direct investments. Tax administration is cumbersome and time consuming. The burdensome nature of tax filing has been identified as a major factor for the high-cost nature of doing business in Bangladesh and a constraint to improving the investment climate.

An added problem is the large informal economy. Most small and micro enterprises escape the tax net because they operate outside the formal system and are not registered with the government either through business licenses or through tax identification number. The fear of taxation in terms of harassment is so large that small firms prefer to stay informal and forgo many benefits of government support programs including access to formal credit. In this regard, the tax system may work as an important deterrent to the growth of small enterprises and employment.

Problems of tax administration are also acute in the case of the VAT. The many exemptions and the inability to extend the VAT fully to the retail level, many services and to small and micro enterprises along with evasion and tax administration inefficiencies have sharply lowered the productivity of the VAT. Even for firms that are registered, the compliance rate is estimated at 12%.

In recognition of these difficulties and prodded by the IMF, the government in 2012 enacted a new VAT Law. The Law simplified and modernized the VAT along with provisions for major improvements in VAT administration including the shift from manual to electronic filing, voluntary approach to tax compliance, broadening of the tax base, single registration for each taxpayer, use of invoice credit method for tax assessment, and simplified VAT refund system. Substantial technical assistance was arranged to prepare for the implementation of the new law. The law was never implemented. Instead, a watered-down version of the original VAT proposal was introduced in the FY2019-20 Budget. Analysts are skeptical that this reform will be very effective in improving VAT productivity revenue collection.

Implementation of taxes on international trade is more organized and better administered. Nevertheless, many problems remain. On the revenue mobilization side, the main problem is tax evasion based on collusive behavior between importers and the customs staff. This is a governance challenge that permeates throughout the tax administration. Additional issues emerge for private investment in terms of high transaction costs of doing business at the ports. Despite progress in simplifying clearance procedures and valuation, the transaction costs remain high as indicated by the World Bank’s Ease of Doling Business indicators.

A generic problem in tax administration is low tax capacity. The National Board of Revenue (NBR) lacks autonomy and is run like any other government department. It is staffed by civil servants. Its primary focus is tax collection through policing and threats. There is no concept of tax service or seeking voluntary compliance through user-friendly approaches.

There is very little capacity to do tax policy analysis. Tax changes are made in almost all budgets. There is little analysis of the revenue and resource allocation impact of these changes. This lack of separation of tax policy and tax collection and absence of capacity of NBR to do proper tax policy and analysis is a severe institutional constraint that has hurt fiscal policy development. In situations where a reform-minded NBR chairman has sought to bring about tax administration changes, this has failed because the chairman was replaced before implementation can begin. Frequent changes at the top (chairman NBR) has further reduced the ability to reform NBR.

Reforming the taxation system: The major tax reforms needed for UMIC status include:

Separation of tax policy from tax collection: An essential institutional reform is to separate tax policy from tax collection. A better arrangement would be to assign NBR the primary responsibility to collect taxes and give tax policy responsibility to either a special unit within the Internal Resource Division or to the Budget Division of the Ministry of Finance.

Strengthening tax policy and tax collection agencies: Whatever institutional arrangements the government may adopt, both tax policy and tax collection efforts have to be substantially strengthened through induction of better professional staff. The government has substantially increased civil service salaries in recent years that has improved incentives for professional staff to apply for public service positions. The tax departments (NBR and the tax policy unit) need a much stronger combination of professional staff with civil service staff. If needed, some additional incentives could be provided to attract fixed-term tax professional experts to the Ministry of Finance. This small investment in building up the tax administration capacity has a high rate of return in terms of better tax policy and revenue performance.

Selection and tenure of NBR Chairman: The government might want to delink the NBR chairman position from the civil service, select the chairman on a professional basis, and establish a minimum tenure of 4-5 years. This will strengthen the quality of tax administration leadership, de-politicize this position, and provide stability and incentive for the chairman to take tough actions against corrupt practices.

Fully digitizing tax administration: Full digitization of tax administration, especially personal income taxation, will be an important way to reduce corruption, increase compliance and increase tax revenues.

Shift from tax harassment to tax service: The attitude of NBR should change from tax “policing and harassment” to voluntary tax compliance based on a user-friendly and tax service approach. Self-assessment, digitization, and simplification of tax filing with a user-friendly and service-oriented approach will vastly increase tax compliance and tax collections as reflected in the experience of countries with good tax collection record.

Reforming the VAT: The best approach would be to go back and implement the original VAT Law 2012.

Reform of corporate income taxation: With the exception of tobacco, the maximum rate of taxation should be lowered to 30% in FY2021 and 25% in FY2022. As rates come down, exemptions and tax holidays for FDIs or specific sectors must be eliminated over a well-defined period so that by and large all investors are required to pay taxes. Once the tax rates are lowered and made internationally attractive, exemptions will not be needed because the investor will have to pay taxes in other countries as well.

Reforming the personal income taxation: The required reform is to increase the tax base through voluntary compliance. The tax system must be based on the principle of universal income and self-assessment with productive and selective audits. It must be fully digitized wherever possible with no interface between the tax payer and tax collector, except when subject to audits. The tax system must be simple with low compliance cost. The audit system should be highly selective and productive, based on a computer-driven model developed on the basis of well-identified criteria that if violated would trigger an audit. The criteria must make the audit productive so that the collection cost is only a fraction of total taxes raised through audits.

Reforming the customs system: The NBR has recently adopted a new customs reform program known as the “Customs Modernization Strategic Action Plan 2019-2022” that seeks to improve the efficiency of the customs system and reduce transaction costs related to international trade. This is a welcome initiative and its sound implementation should be a high policy priority.

Reforming public enterprises for long-term fiscal solvency

Bangladesh government has invested a huge amount of resources on a range of commercial activities including banks, electricity and gas supply, transport, manufacturing, hotels and tourism. Most of these state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are poorly managed, are riddled with corruption (especially public banks), the financial performance is very bad with most enterprises requiring operational subsidies to survive, and consequently they constitute a huge burden on the Treasury.

The current finances of SOEs: As result of the rapid accumulation of deficits and investment financing needs, outstanding debt liability of SOEs has climbed from Taka 781 billion in FY2010 to Taka 2146 billion in December 2018 (Table 4). This is a huge contingent liability of the Treasury amounting to almost 10% of GDP emerging from the inability of SOEs to cover operational deficits and finance own investments. In recent years the sharp deterioration in the non-performing loans (NPLs) of state- owned banks is another source of contingent liability of the Treasury. The NPLs of public banks soared to Taka 487 billion in December 2018 (2.3% of GDP). Operational deficits of SOEs and NPLs are causing a serious drain on the limited Treasury resources. Every year the budget is setting aside resources to finance the deficits of SOEs. As an example, energy subsidies alone climbed to Taka 181 billion in FY2013 (1.5% of GDP). In the last few years, the Treasury has also been setting aside substantial resources to recapitalize public banks.

The social cost of supporting these perpetually loss-making enterprises through the national budget raise some serious issues. Should Bangladesh spend scarce public resources for financing oil subsidies that are regressive in nature (the richer population gets a larger share of the subsidy than the poorer population) or for educating the children? Should Bangladesh divert tax payer money to fill the hole left by bad lending decisions, theft and other corrupt practices in public banks or use those resources for financing social protection programs for the poor? Should Bangladesh be financing the deficits and servicing the debts of SOEs from Treasury resources instead of requiring them to earn an adequate rate of return on invested assets that allows them to finance own investment and debt servicing obligations? These are tough policy and ethical questions that need substantial debate in the National Parliament, the cabinet and in public domain for speedy resolution.

The way forward: These issues will need to be swiftly addressed and resolved to maintain long-term fiscal stability and also to ensure the best use of limited public resources. Except in the case of pure public good, the case for public provision of commercial goods and services is weak. Yet, if the government wants to continue with the SOEs, it must impose a hard budget constraint and require them to earn an adequate rate of return on invested assets. Subsidies must be limited to a few strategic services (e.g. mass transit, water supply, sewerage) and most enterprises, especially manufacturing enterprises, should be converted to profit-making ventures through proper restructuring.

Regarding public banks, the best course of action would be to privatize all public banks except one bank (Sonali) that would primarily handle Treasury functions. If privatization is not a practical option, the next best option is to convert public banks into narrow banks that can mobilize deposits but cannot do any lending functions. They can use the deposits to invest only in safe assets, such as T-bills. The third best option is to keep them functioning as commercial banks but they should be required to perform on strict commercial principles and earn profit. The bank management should be held accountable for performance. These banks must be fully supervised by the Bangladesh Bank and be required to comply 100% with all prudential regulations. No budget transfers should be made to keep any public bank alive.

Promote fiscal decentralization

Despite some progress with political and administrative decentralization, Bangladesh has not made any inroad on the issue of fiscal decentralization. Absence of fiscal decentralization has constrained the emergence of autonomous and accountable local government institutions (LGIs). It has also reduced the quality and delivery of core basic services like health, education, nutrition, water supply, drainage and irrigation.

The magnitude of the fiscal decentralization challenge: A review of international evidence suggests that Bangladesh is fiscally amongst the most centralized countries in the world measured in terms of both expenditures and taxes. Data from a sample of 16 developing countries and 26 developed countries shows that spending by all LGIs (urban and rural) account for 19% of total government spending in developing countries and 28% for industrial countries as compared with only 7% in Bangladesh. Taxes similarly are heavily centralized in Bangladesh. Thus, subnational government taxes account for 11.4% of total taxes in a sample of 16 developing countries and 22.7% in a sample of 24 industrial countries. In Bangladesh it is only 1.6%.

The evidence that cities of industrial countries tend to have better services and significantly higher fiscal decentralization is no accident. A system of well-defined revenue sharing and resource arrangements not only provides larger funding but predictability of resources makes it that much easier to plan and provide better services. Good city governance and fiscal autonomy tend to support better urban services.

Lack of fiscal autonomy and associated resource constraint reduces the ability of urban LGIs to provide adequate service in a number of ways: (1) Weak fiscal decentralization contributes to grossly inadequate resources that in turn lead to poor capacities of urban LGIs to deliver services. (2) Inadequacy of staffing in both quantity and quality is a major bottleneck. (3) Political patronage and centralized decision-making on urban spending results in poor accountability of city governments. (4) Since transfers have no legal basis and are discretionary, there is no predictability of resources. Government control over revenues and spending essentially means that elected urban city managers belonging to opposition have little control over service delivery. (5) Even in cities that have managers who belong to the party in power, service delivery is constrained by inadequacy of resources at the national level. (6) The scope for innovative financial solutions at the local level is limited by the weakness of the property tax design and national-level control over pricing policies for services.

The way forward: The government’s PP2041 growth strategy seeks to achieve growth rates in the range of 8-9 percent per year, based on transforming the economy into a manufacturing and organized services-oriented production structure. This growth strategy will accelerate the urbanization process, as labor continues to shift from low-income agriculture and rural informal services to urban-based manufacturing and organized services. Without a major effort to improve the growing urbanization challenges, there is a real risk that the growth momentum is constrained by transport bottlenecks, high land prices, and inadequacy of infrastructure and basic urban services including housing, urban water supply and waste management.

It is simply impossible that Bangladesh can achieve UMIC status without addressing the urbanization challenge. Good practice international experience suggests that on substance there are two major and big picture agenda that will have to be addressed. First is the need to address the urban finances issue. And second is need to tackle the urban governance challenge. The two are inter-related and will need to go hand-in-hand. The basic challenge is to establish a system of accountable city government that is publicly elected, enjoys considerable political and administrative autonomy, is responsive to the needs of the residents and not to the national government, and has considerable financial autonomy.

The strategy for urban financing essentially calls for a substantial decentralization of the fiscal system encompassing taxes, service charges, predictable transfers and responsible borrowing. On the tax front, the main reform will be to overhaul the system of property taxes based on digitized property records, market-based valuation and initial low rates that can be adjusted upwards as LGI services improve. Service fees must seek to provide full cost recovery and better quality of services. The system of fiscal transfers must be depoliticized and based on a well-articulated devolution strategy that matches grants to assigned responsibilities, population size, poverty and incentives. The transfer system once agreed must be enshrined in the legal framework to ensure predictability and depoliticization. LGI borrowing can be a good option for financing large urban infrastructure only when LGIs have matured and are fiscally capable of servicing their debt.

Dr Sadiq Ahmed is vice-chairman, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI). sadiqahmed1952@gmail.com