Published: May 16, 2022

For the rising Bangladesh economy, these are the best of times. These are also the worst of times. A combination of good news and bad news pervades the media world, with news of protracted economic impacts reverberating around the globe. Can Bangladesh economy be immune to this evolving global scenario?

GLOBAL CONTEXT: The forthcoming budget can hardly avoid taking stock of global developments – geopolitical and geoeconomic. Global developments call for rigorous analysis and policy actions at the national level. The circumstances suggest that business-as-usual (BAU) cannot and should not be the stance of the FY2022-23 budget.

The global slowdown has not yet dampened our exports which are surging at a record clip of over 35 per cent year-on-year and is likely to close the year even higher. Imports are growing even faster at 46 per cent for the year – a sign that post-pandemic economic recovery remains strong as 75 per cent of our import basket is made up of raw materials, intermediate goods and capital goods meant for the productive sector of the economy. Official remittance figures show muted growth to end the year with about 2 per cent with clear indication that remittance senders are choosing the more profitable option of unofficial channels where the exchange rate on offer is significantly higher than the inter-bank rate plus the 2.5 per cent cash incentive.

But the Russia-Ukraine war coming on top of the supply chain disruptions caused by the two-year pandemic has delivered a double whammy of trade and output shock on the one hand and rising inflation on the other. Food and energy prices are up globally, near 7-8 per cent inflation in the United States (US) and Eurozone. The specter of a “stagflation” shock to the world economy looms, perhaps with some difference from the inflation-unemployment variety of the 1970s. In the US, a tight labor market with a mere 3.6 per cent unemployment rate prevails while inflation has crossed 7.5 per cent. Bangladesh cannot be immune to these developments. Much of Bangladesh’s price spiral in essential commodities is caused by imported inflation. But, as we will see in the ensuing analysis, not all is lost for the Bangladesh economy.

One clear message that is emerging from global developments is that the so-called post-Cold War ‘peace dividend’ is all but over. From the ashes of the current European conflictwill likely emerge a new geopolitical order that threatens to eventually reshape the rules-based Bretton Woods geoeconomic order. Already, US-China trade and technology centered tensions have dealt a debilitating blow to the rules-based trade order encapsulated in the WTO regime.

We see populist politicians openly hostile to the march of globalisation are gaining ground in so many developed countries.In consequence, the prerogative of the nation-state is gaining precedence over the demands of an open and competitive global economy. Protectionist tendencies are on the rise again. In developing economies like ours, which benefited immensely from the Bretton Woods trade order, our hope is that the world economy has come a long way, gained hugely in terms of income and jobs growth over 70+ years of trade openness, and developed a manufacturing export base counting on market access to the largest economies of the world; all of these gains cannot and should not be abandoned through the reversal of the “liberal” principles enshrined in the post-WWII world trade order. Global communities have learnt enough not to repeat the mistakes of the tit-for-tat tariffs of the 1930s Depression years.

A new world order is shaped by world leaders. Our hope is world leaders have learnt enough from past economic history not to repeat it.

THE NATIONAL CONTEXT: As we move into the next budget cycle the economy must address inter alia at least three inter-linked policy issues on a priority basis. Some of this might appear in the budget policy statement while others could be part of budget implementation.

First, there is the problem of moderating the import surge of 46 per cent plus in the current fiscal year. Predictably, this has put pressure on the exchange rate to depreciate though the pick-up in exports and steady inflow of remittances is expected to keep the current account deficit within a sustainable range of 2.5 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at the close of FY22. The nominal exchange rate is nothing but the price of foreign exchange and a key instrument for managing import flows. A depreciation will raise import prices, and curb imports while stimulating exports. An appreciation will do the opposite, not instantaneously but over a period of time. In theory, exchange rate flexibility ensures stability in the balance of payments. So, what should be the approach to exchange rate flexibility?

The Bangladesh scenario and exchange rate stance over the years may not be suitable for fully floating exchange rate even though that is the official exchange rate regime since 2004. A managed float is what we are used to. Yet, in the short-term there is a build-up in exchange market pressure triggered by the import surge in excess of export and remittance earnings thus causing a divergence of 7-8 per cent between the inter-bank and curb market rate (resulting from excess demand over supply of foreign exchange). Under the circumstances, Bangladesh Bank has been selling foreign exchange from official reserves (potential depletion) to keep the nominal exchange rate steady at Tk 86.5 to the dollar, as of this writing. In the absence of the quantitative restrictions (QRs) regime that was finally abandoned in early 2000s, to protect current moderate level of official FE reserves (running at about 6 months of projected imports) and prevent further depletion BB is trying to put the brakes on imports through administrative measures (e.g. imposing higher margin requirements) which is a step in the right direction. But this could be too little too late. The better option we believe would be to infuse flexibility to the nominal exchange rate, preferably to let it depreciate another 4-5 per cent over the next few months – a process that BB has probably already started and would be well advised to continue. Research evidence shows that an undervalued exchange rate is the strongest support for export of goods as well as factor services (remittance). For the lay reader it would be good to know that a 5 per cent exchange rate depreciation is the equivalent of a 5 per cent cash subsidy on exports and remittances that does not have to come out of the Treasury.

But the price effects of exchange rate depreciation could be inflationary. That brings us to the second policy problem.

Second problem is inflation – now a global issue. Latest official estimates of general inflation runs at 6.2 per cent y-o-y though actual rate could be significantly higher. The problem will have to be addressed swiftly in order to prevent the erosion of income particularly of the poor who suffer the most from inflation and who already suffered from income losses during the pandemic. Here again if the source of the problem is imported inflation, one of the ways this problem can effectively be tackled is at the border. Fundamental principles of market economy suggest that market prices of essential consumer staples cannot be brought down by suppressive crack downs and the like, as such actions will only lead to hoarding and further dwindling of supplies. The solution lies in increasing supplies to the market not decreasing it through crackdowns. If some consumer goods, like palm and soya bean oil, are all imported, two things need to be done to get their market prices down: (a) take necessary steps to increase supplies from imports, and (b) temporarily eliminate tariffs or substantially reduce it for both crude and refined, as an emergency measure. Other consumer goods might also need tariff reduction to stimulate supplies. That brings us to the next interlinked policy problem.

Third thing is tariff rationalisation which is an issue waiting to be addressed and resolved, now more than ever. It is not just that we need to prepare for Least Developed Country (LDC) graduation in 2026. Properly done, it is the most effective instrument for lowering domestic prices of consumer goods as well as to eliminate the unique Bangladeshi situation of anti-export bias of trade policies that is preventing export diversification.

But first things first. One essential consumer item is edible oil – soya bean oil (SBO) and palm oil (PO). International prices have shot up. Custom duty on both SBO and PO have been eliminated in the hope that domestic price will moderate and only reflect international prices. Instead, local market prices have hit the roof and there is a crackdown on so-called hoarders. Why is the duty relief not working?

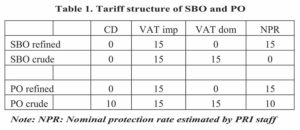

Here is a quick review of the simplified tariff structure of SBO and PO (Table-1). Nominal protection rate is what impacts market prices. Although CD=0 for both refined

SBO and PO, it is the setting of VAT domestic to zero while keeping VAT import at 15 per cent that is keeping market prices up with NPR at 15 per cent. Effective protection rate (ERP is a measure of profitability), which takes into account value addition in the refining process, is substantially higher than 15 per cent, because edible oil refining is a low value addition activity and ERP is an inverse function of value added.

For the forthcoming budget, VAT should be made trade neutral. In this case, to keep prices low, set both VAT import and domestic to zero and NPR becomes zero. Then domestic prices will reflect international prices plus a modest mark up, unless government wants to subsidize, which I think will open a pandora’s box. Of course, there is advance income tax (AIT) and advance VAT (AV) as part of overall trade taxes on edible oils. (Anyone interested in understanding the complex tariff structure on edible oils and other consumer products can contact PRI for clarification.)

Fourth thing is the tariff rationalisation issue. There is no doubt that Bangladesh economy is on a path of strong post-pandemic recovery in the current fiscal year. This trend should be maintained for the next couple of years by driving the export engine even higher – both ready-made garment (RMG) and non-RMG exports. There is opportunity to be seized in the world market. Geopolitical developments around the Russia-Ukraine war and US-China trade tensions, among others, presents tremendous opportunities for the Bangladesh export sector (goods and factor services alike) to fire on all cylinders while the going is good. FY23 Budget must strategise on how to seize the opportunities presented in the world market. Reports are that the Government has taken the issue of tariff rationalisation with utmost urgency and work is ongoing in the appropriate ministries. Perhaps we shall see some results in the forthcoming budget.

To be fair, the global economy has hit headwinds that could be lasting. But the market for apparels is not known to be shrinking. So is the case with other labour intensive manufactures where our market share is infinitesimal (much below 1 per cent), implying that there is tremendous opportunity to expand non-RMG exports (e.g. footwear, electronics, plastics, ceramics, specialized textiles). With oil prices rising demand for our migrant workers should be strong over the next few years. Remitters deserve an incentivizing exchange rate rather than 2.5 per cent cash from the Treasury.

Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI) research in the past has revealed the contradiction between our goal of export diversification and high tariff protection for domestic sales from import substituting industries. Export diversification cannot have any traction under the current tariff regime. Now is the time to turn the corner and the forthcoming budget can do just that. Let me describe the opportunity.

For a rapidly growing economy like Bangladesh, poised to graduate out of LDC status, the current tariff structure is an outlier in the world tariff scenario. At 27 per cent average nominal tariffs in FY22, it is higher than that of low income countries (11 per cent), lower middle income countries (7.2 per cent), Upper Middle Income Countries (3.7 per cent), and the global average (6 per cent). The problem is that our tariff structure militates against the national goal of export-led inclusive growth and the pursuit of export diversification. PRI research has demonstrated with evidence that our current protective tariff structure makes domestic sales far more profitable than exporting, particularly for the non-RMG exporters who are the candidates for export diversification.

Understandably, in the past there has been a strong resistance to tariff reduction on grounds of revenue loss. But here is the opportunity in the current and forthcoming fiscal year! Both imports and exports are surging not just by double digits but by 46 per cent and 35 per cent respectively. With all the tariff exemptions, typically Customs collects some 16-17 per cent of import value as revenue. That revenue will be expanding by at least 45 per cent by year-end yielding customs revenue of $14.4 billion (Tk.124.9 billion) in FY22. Add 3-5 per cent exchange rate depreciation which will further raise the value of imports by that percentage yielding extra revenue from depreciation. This presents a golden opportunity for cutting tariffs without loss of revenue or protection. Regulatory duty (RD) of 3 per cent can be easily removed in one stroke; OR the top CD rate of 25 per cent, which has been stuck at that number since 2004, can be brought down by 2-3 percentage points, all without any loss of revenue; OR, some supplementary duty (SD) can be cut. Indeed, those who think they might lose profits from domestic sales should know that the exchange rate depreciation of 3-5 per cent will make up for the modest reduction of average nominal protection. More important, the tariff cuts will neutralise the inflationary effects of exchange rate depreciation to keep prices of consumer goods stable. This is just the right time and opportunity beckons to do some deep thinking on tariff rationalization for an economy that is cut out to prove to the world that our workers and entrepreneurs are hardworking, innovative, and competitive in the global marketplace. Tariff follies cannot and should not keep them back.

All in all, despite the crisis in the global economy, Bangladesh economy appears to be dealing with a different kind of beast. Prices are up, but so are exports and imports to fuel a strong economic recovery to keep the economy humming on all cylinders for the current and next fiscal year at the very least. We look forward to the FY23 Budget to come roaring and propel this momentum.

Dr. Zaidi Sattar is Chairman, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI).

zaidisattar@gmail.com