Analysts think better access to microcredit and social protection programmes may help reduce poverty on a sustainable basis. Photo: Sk Enamul Haq

Bangladesh has set an ambitious target to eliminate extreme poverty by FY2031. The results of the latest Household Income and Expenditure Survey done in 2016 (HIES 2016) suggest that this is a feasible target but by no means assured. HIES 2016 shows that moderate poverty (percent of population below the Upper Poverty Line or UPL) has fallen from 31.5 percent in 2010 to 24.3 percent in 2016, while extreme poverty (percent of population below the Lower Poverty Line or LPL) has declined from 17.6 percent to 12.9 percent over the same periods.

Research shows that several factors have contributed to continued progress with poverty reduction in Bangladesh including rapid economic growth, public spending on health, education, social protection and infrastructure, rapid inflow of external remittances and expansion of micro-credit programmes. Continued progress on these fronts will be important for further poverty reduction.

These research findings have been internalised in the government’s poverty reduction strategy and related policymaking. But there is one major policy gap that has not received adequate attention. Research shows that poverty and the population’s vulnerability to natural disasters are positively correlated. Those falling in the extreme poverty group are most susceptible to natural disasters owing to the absence of adequate coping mechanisms. Yet, policy progress with reducing the vulnerability of the poor to natural disasters has been weak. Continued neglect of this aspect of poverty strategy could jeopardise the government’s ability to eliminate extreme poverty by FY2031.

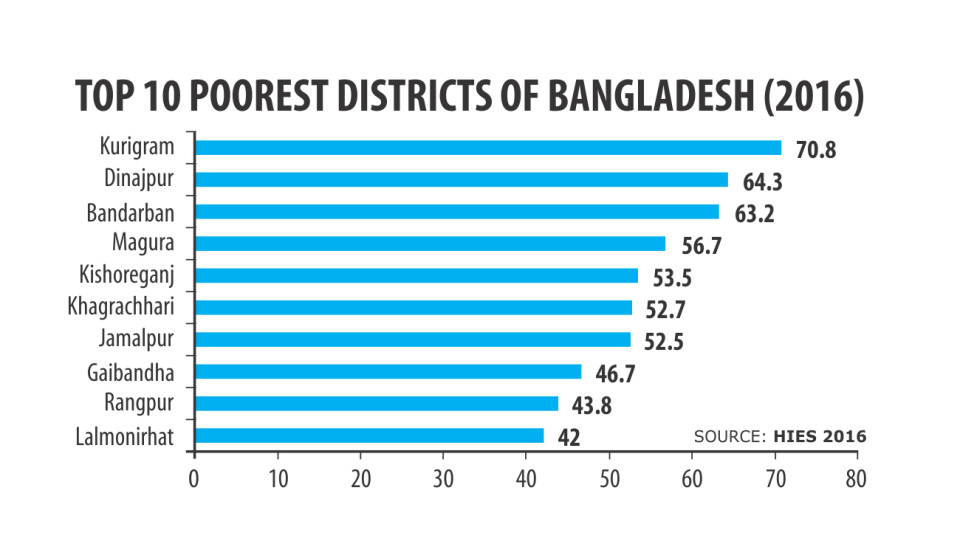

The importance of this policy challenge is well illustrated by the results of HIES 2016. District level data indicates that the poverty reduction progress has been highly uneven. The chart shows that the top 10 poorest districts of Bangladesh have poverty incidence ranging from 70 percent to 42 percent (based on UPL) as compared with the average poverty incidence of 24.3 percent. Indeed, the poverty gap between the poorest district (Kurigram with 70 percent poverty rate) and the least poor district (Narayanganj with a poverty rate of only 2.6 percent) is astounding.

A 70 percent poverty incidence found in Kurigram even after 45 years of independence is truly worrisome. A deeper analysis of the determinants of these large spatial variations in poverty incidence must be done to inform policymaking. An important factor is the role of geography and exposure to natural disasters. Kurigram is an extreme example of this. Year after year Kurigram suffers from massive flooding from the overflow of the Brahmaputra river. It is little comfort to give the exposed population annual dose of relief supplies, small financial handouts, access to microcredits and better toilet facilities. Unless a permanent solution to the river flooding problem can be found, Kurigram will continue to show high poverty and thwart the government’s efforts to eliminate extreme poverty.

More generally, the location map of the top 10 poorest districts shows that they are either a part of the Barind Tract area of North-West Bangladesh (Dinajpur and Rangpur) or a part of the river and estuary belt (Lalmonirhat, Kurigram, Gaibandha, Jamalpur, Magura and Kishoreganj). Because of location, they face a range of vulnerabilities presented by river-flooding and water-logging in the monsoon and water shortages in the fall and winter dry seasons. The remaining two (Bandarban and Khagrachhari) are a part of the Chittagong Hill Tracts with little access to usable water combined with difficult land terrain and episodes of flash flooding and land-slides from water runoffs. The environmental problems are compounded by over-exploitation of ground water and deforestation.

All these districts are heavily dependent upon agriculture for livelihood that makes them so much more vulnerable to river flooding, flash floods, water logging, soil erosion and water shortages. Without a sea change in the poverty reduction strategy that is targeted to benefit these districts through specific interventions to reduce the vulnerabilities imposed by geography, natural disasters and climate change, there is a huge risk that these districts will not benefit in a sustained manner from the current poverty reduction strategy and will continue to be left behind as presently. This will likely compromise the government’s ability to eliminate extreme poverty by FY2031.

What is the way out? The adoption of the government’s Delta Plan 2100 (BDP 2100) will be a major step forward. The BDP 2100 identifies the major sources of vulnerability of the population of Bangladesh to geography, natural disasters and climate change and seeks to address these vulnerabilities at source through a well-thought strategy comprising policies, regulations, institutions and investment programmes.

If the government is serious about eliminating extreme poverty by FY2031 it must move speedily to adopt the BDP 2100 and initiate its implementation.

Tinkering at the margin in these districts with small scale safety net or micro-credit programmes will likely be a wasteful use of resources when measured against sustained long-term impact. Sources of vulnerabilities must be addressed to achieve sustained progress with poverty reduction and this will involve large scale public investments in flood control, river training, irrigation, water storage, piped water supply and proper operations and maintenance (O&M) practices.

Degradation of land and underground water resources from deforestation, soil erosion and over-exploitation of ground water must be checked and reversed through regulations, investments and sustainable cropping practices. Institutions must be established and cost recovery policies instituted to ensure participation of beneficiaries in policymaking, adoption of correct O&M practices and sustainable financing of investments. Production diversification must be ensured to create off-farm jobs in small scale manufacturing, transport, trade and other services. Improving access to international migration will be helpful by increasing the income base of the vulnerable families.

Better access to microcredit and social protection programmes will also help reduce poverty on a sustainable basis provided these interventions are a part of the broader strategy that seeks to reduce poverty by addressing vulnerabilities at the source.