For the better of the past month the town has been abuzz with budget talk and, alongside serious policy discourse, a lot of kite-flying has gone on. In my humble view one dimension of the economic implications of the exchange rate shock experienced in the past year has been least understood, let alone discussed threadbare. A one-time exchange rate depreciation of 25 per cent, which is what happened in the past year, happens rarely. For Bangladesh, it was the first time the exchange rate had to be adjusted by that magnitude. We cannot simply wish away the price effect of this shock on market prices.

First, let us get these principles right out of the trade economics textbook which says that an exchange rate depreciation is the equivalent of an export subsidy and an import tax. In the Bangladesh context, the 25 per cent depreciation has had the effect of raising the average nominal tariffs from 27 per cent in June FY2023 to 33.75 per cent, after the depreciation shock. A customs duty of 20 per cent on an imported good of Tk 100 used to yield Tk 20 in revenue. After the depreciation, that same import now has an assessable value of Tk 125 yielding Tk 25 as revenue – a 25 per cent increase in customs revenue without any legislation required. NBR has been reaping customs revenue at this higher rate following the depreciation shock though import controls have dampened the extra revenue collection from trade taxes. Yet, PRI projections show that NBR will be collecting 28-30 per cent of its revenue from trade taxes this year against 26 per cent share of trade taxes in recent years.

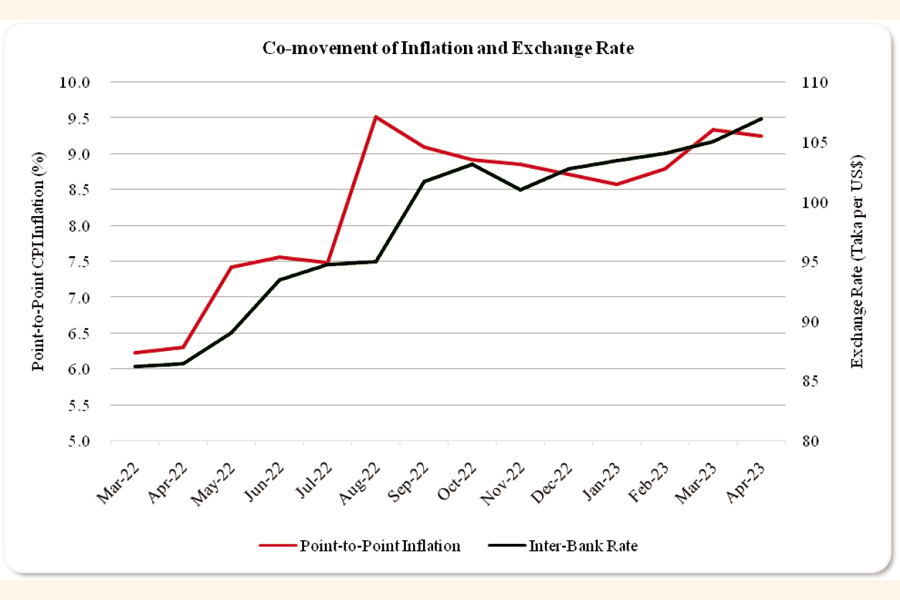

Another principle to note. An exchange rate depreciation is inflationary. An exchange rate shock of the kind witnessed is even more inflationary when coupled with a spike in import prices. The price impact feeds through all traded and tradable goods in the domestic market and, eventually, fuels rise in price of non-traded goods (and services). The price of imported and local onion was Tk 34/kg in March 2022. It is now selling at over Tk 50/kg. A big part of it is caused by imported onion prices which now cost at least 25 per cent more due to exchange rate depreciation, even if onion price in the sourcing country may not have changed. The same is true for many other consumer and industrial goods across the market. The national inflation rate which was 6.2 per cent in March 2022 has increased by 50 per cent to 9.34 per cent in March 2023. A major part of this sharp rise in inflation can be attributed to the exchange rate shock.

Whereas monetary expansion can also fuel inflation there is a time lag for that to happen. On the other hand, in the Bangladesh marketplace, the effect of depreciation and spike in import prices show up contemporaneously (almost immediately) in domestic inflation. That is exactly what we see happening in our neck of the woods.

The chart (using BBS and BB data) shows the co-movement of inflation and exchange rate since March 2022. The inflationary consequence of exchange rate depreciation is clearly evident in the marketplace and expected to last for some time unless some countermeasure is taken.

Let me reiterate that this Bangladesh inflation is markedly different from what happened in United States of America (USA) and Europe. In those economies, whereas monetary easing since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 had already caused their economies to be flushed with cash the Covid-pandemic response added fuel to the fire. Central banks in USA and Europe are trying their best to dowse that fire through interest rate hikes and monetary controls to subdue credit and consumer demand. In those economies, the underlying principle is that inflation is a monetary phenomenon and must be controlled through monetary management. Reports suggest that that is working but, at least in the USA, spikes in the interest rate are slowing down the economy with potential uptick in the unemployment rate. Should that be a policy to follow in Bangladesh?

In Bangladesh the policy choice is as follows. We have no control over international prices of importable commodities. The exchange rate depreciation of 25 per cent is here to stay and could get worse if we don’t bring the overall balance of payment in positive territory soon enough. Any attempt to manage the interbank exchange rate to, say, bring it below Tk.100/US$ will cause a loss of foreign exchange reserves. So that is out of consideration.

One lethal weapon that could have immediate and substantial impact on inflation is the tariff handle. There is scope for neutralizing the inflationary effect of depreciation through tariff adjustment. As it is Bangladesh has among the highest tariffs among its peers. It is now accepted that such high rates (for revenue or protection) create anti-export bias that subverts incentives to diversify our export basket away from readymade garments. Under the current tariff regime producers of non-garment exportable commodities find it more profitable to sell in the domestic market than to export. Now that the exchange rate depreciation has given a boost to the prevailing tariff rate by a massive 25 per cent it creates an excellent opportunity to reduce and rationalize tariffs (without worrying about revenue loss) thereby killing three birds with one stone: (a) crush inflation, (b) reduce anti-export bias and propel export diversification, and (c) attract FDI by infusing dynamism through a more open trade regime.

Given that the economy is being challenged on many fronts and an International Monetary Fund (IMF) program is in operation one would have hoped that this would be the most propitious time for undertaking radical tariff rationalization. Yet, to be realistic, one can only talk of modest steps which could still have notable impacts. This is the time to reduce the top customs duty (CD) rate of 25 per cent (which has been stuck at that rate since 2004) to 20 per cent in one stroke. If that is considered too much then another modest option would be to simply not impose Regulatory Duty (RD) this year. RD is basically an addition to the top CD rate of 25 per cent imposed every year almost across-the-board at 3 per cent rate, with some higher rates as exception. Either of these ‘bold’ steps could shave off 1-2 per cent of the current official inflation rate of 9.3 per cent.

In economics another name for inflation is a ‘regressive tax’ because it adversely affects the poor much more than those who are better off. Needless to say the current inflation is causing too much pain on a vast swath of our population who are crying out for succor. The FY2024 Budget has at its disposal the tariff handle to tame or crush the inflation bug. Some effective action will be welcomed by all.

Dr Zaidi Sattar is Chairman, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh. zaidisattar@gmail.com

https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/views/gig-economy-as-a-new-form-of-economic-transformation