It is heartening to learn that the newly elected government is keen to address the menace of non-performing loans (NPL) in Bangladesh. This is appropriate because

restoring the financial health of the banking sector is critical to securing the GDP growth and poverty reduction targets of the Perspective Plan 2041. The main challenge is to ensure that the policy reform is well-designed to comprehensively address the NPL problem and not seek quick fixes that simply postpones and magnifies the resolution. This article seeks to provide some inputs to the government’s efforts to get a satisfactory NPL reform programme.

What is NPL: Banks operate as financial intermediaries. Bank owners put up a minimally required amount as equity or capital that then allows them to mobilise deposits which are loaned out. Banks offer depositors a return on their deposits (average deposit rate) and charge borrowers a loan rate (average lending rate).

The spread or gap between average deposit rate and average lending rate allows banks to finance their business costs and earn profit on their equity. Every loan has a repayment schedule comprising of repayment of principal and interest. A loan becomes NPL when the borrower is unable to pay the scheduled principal and interest for more than 90 days. As the size of NPL grows the financial health of the banking sector weakens because it reduces its ability to earn profit, increase capital base and repay depositors. When the NPL problem grows very large, it could jeopardize the entire banking sector through bank failures and liquidity crisis.

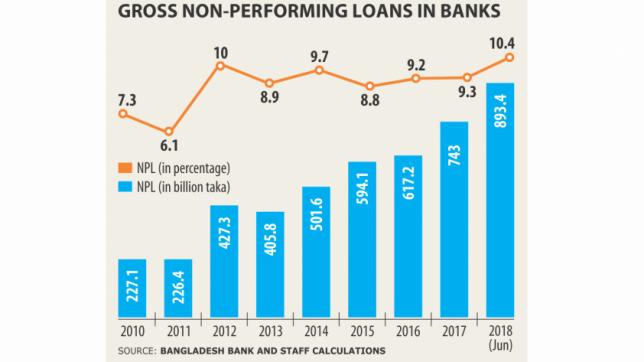

As of June 2018, gross NPL amounted to Tk 893.4 billion ($10.8 billion). It was 10.5 percent of total outstanding loans. There are two points to note: one is the upward trend in NPLs as a percent of total loans and the other is the growing size in value terms. On both counts, NPL is a major threat to the financial health of the banking sector and the government’s concern to address this threat is well placed.

Gross versus net NPL: One strand of argument is that gross NPL overstates the magnitude of the problem. Since prudential regulations require that provisions should be kept against NPL, the net NPL that takes out the amount of provisions from gross NPL is the true liability of the banking sector. A related argument is that the NPL figure includes accumulated interest on the suspense account. Since this interest has been on the books for a long time (many years) and is not likely to be paid, it should be taken out of NPL calculations.

Under current Bangladesh Bank regulations, provisioning requirements are 0.25 percent-5 percent for unclassified loans; 20 percent for sub-standard loans; 50 percent for doubtful loans and 100 percent for bad loans.

According to prudential norms interest accumulated on sub-standard and doubtful loans cannot be shown in the income statement but kept under a special account called Interest Suspense Account. When a loan is declared bad (overdue 9 months or beyond), interest accumulation stops completely.

The size of gross NPL is calculated by adding up sub-standard, doubtful and bad loans and the accumulated interest thereon. Capitalisation of interest can happen up to a maximum of 9 months, since, according to established regulation, interest can no longer be accrued when a loan turns bad.

So, the argument that gross NPL is padded up by many years of accumulated interest on bad loans is not valid.

Regarding gross versus net, while it is true that the immediate macroeconomic risk is presented by net NPL because that amount is uncovered by provision, the gross NPL is a true reflection of the long-term financial health and sustainability of the banking sector for the following reasons:

First, banking is a business. Owners invest a sizeable equity as a part of minimum required capital. Banks then mobilise deposits on which they have to pay interest. They also incur substantial operating cost. Unless they earn money on their loans, they will not be able to stay in business. So, interest earning on total assets (loans) is a critical determinant of a bank’s financial sustainability.

Second, if NPL grows and banks face a threat to their profitability, they will respond back by raising the interest on loans that will penalize good borrowers and hurt economic growth.

Third, provisions can only be kept if banks earn money. The larger the size of NPL, the larger the amount of required provisioning. If profit is being eaten up by NPL, then banks cannot keep provisions for long and will eventually default on their obligations and go out of business. The economic consequence of this will be devastating.

Finally, there is considerable global evidence that the financial health of the banking sector is negatively correlated with the size of gross NPL. So, the long-term viability of a sound banking system depends on keeping a tight lid on gross NPLs.

Loan restructuring as a solution to NPL: Loan restructuring is a normal aspect of banking business and should be dealt with at the individual bank level as a part of bank-client relationship. The prudential norms of Bangladesh Bank can provide guidelines on how these restructuring operations can be done to be consistent with depositor’s safety.

Restructuring becomes a problem when it gets enmeshed in bad governance or involves public banks. It is well-known that the NPL problem is acute in public banks for a range of reasons including poor governance reflected in loan thefts, poor loan quality at entry, politically-motivated loans, weak loan collections, and frequent loan restructuring with substantial discounts.

The burden of NPL has often been transferred to the tax payers through treasury transfers. This is not only unsustainable as tax revenues become increasingly constrained, it is also unethical. In Bangladesh where there are still millions of poor, using tax revenues to bail out public banks because they have loaned out depositor’s money to bad borrowers who often tend to be very rich and powerful would seem to violate all accepted norms of ethics and morality.

Frequent restructuring on concessional terms can also create moral hazard. Good borrowers will be tempted to also default in the hope of getting concessional restructuring terms.

Finally, restructuring is a means to avoid the pains of an otherwise good borrower facing unforeseen contingencies. It is not a solution to the NPL problem. Unless it is addressed at the roots by resolving all the weaknesses in portfolio quality, the NPL problem will re-emerge.

The way forward: A comprehensive resolution will require the government to bite the bullet and do a proper restructuring of the banking sector based on a sound diagnostic analysis of NPLs of both public and private banks and associated institutional arrangements for regulation and supervision. This diagnosis should be done by a team of experts who are independent and not involved with the present banking system.

A short-cut fix through loan restructuring and redefinition of prudential norms will be like applying band-aid to a cancer wound. Redefinition of prudential norms that are presently aligned to international norms can also jeopardise the international credit risk perception of Bangladesh and must be avoided. The solutions to the NPL problem will need to make a distinction between the stock of NPL and the future flow. The growing stock of NPL suggests that the stock problem cannot be resolved unless the flow problem is addressed.

The writer is the vice chairman of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh. He can be reached at sadiqahmed1952@gmail.com.

https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/addressing-the-menace-npls-1726048