For the world economy 02 April 2025, dubbed by the US Government as “Liberation Day” for the American economy, will be carved in history books as a watershed moment. The newly crafted “reciprocal tariffs” announced on that date take effect momentarily, from 09 April, 2025 without much respite. From the Brettonwoods world of rules-based trade that garnered equal treatment for all World Trade Organization (WTO) trading members under the MFN umbrella we may have entered a strange new world of ‘country-specific’ tariffs ordained by the largest and richest trading economy in the world, the United States (USA). These tariffs, if they last, will fundamentally change world trade.

But there is reason to hold our breath. Immediately after Trump’s tariff announcement, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent took the mic to state, “These tariffs are a cap-not a floor. Countries can negotiate down from them.” That gives a hint that these tariffs are leverage, not dogma. They are meant to force other countries to the table, get them to make concessions, and ultimately, present the scope for rolling them back. That is a line for Bangladesh to pursue, given that it has been listed among the “worst trade offenders”, though much lower in the pecking order.

THE RATIONALE BEHIND RECIPROCAL TARIFFS: National Security. The US government has made the argument that decades of unfair trade has resulted in undermining its national security and economy. Tariffs are justified on national security grounds, especially for industries deemed critical (like semiconductors and defense-related manufacturing).Section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act of 1962 allows for this. So also does Article XX1 of GATT/WTO.

Leveling the Playing Field. The first argument for these tariffs goes like this: If another country imposes high tariffs on American goods, the U.S. should impose equivalent (reciprocal) tariffs in return. That will push foreign governments to reduce their own tariffs or trade barriers so that trade with the US is more balanced.

Restoring US manufacturing. Another argument states that unfair trade of the past decades have led to the hollowing out of US manufacturing, reducing its share in GDP to 10 per cent with barely 8 per cent in manufacturing employment caused by huge job losses. These reciprocal tariffs will bring back manufacturing to US shores as leading manufacturers of semiconductors and technology-intensive industries will have to invest and produce in the USA to sell to US consumers. This is a response to unfair competition, particularly where foreign governments subsidise their exports or maintain high barriers to American products. Example: Tariffs on steel and aluminum to protect US producers from cheaper, subsidized imports. Jeffrey Sachs, a globally renowned economist at Columbia University emphasises that the decline in manufacturing employment in the U.S. is more attributable to technological advancements, such as automation and artificial intelligence, than to trade imbalances. He suggests that imposing high tariffs is a misguided approach that fails to address the underlying issues affecting the manufacturing sector.

Reducing perennial trade deficits. It is argued that tariffs can help reduce large trade deficits with countries that export far more to the U.S. than they import from it, and reciprocal tariffs will lead to more balanced trade flows. Trade experts in the White House argue that the Brettonwoods system has failed them. For decades, as the US opened up its markets to foreign imports leading to an average tariff of only 3.3 per cent, this was not matched by other trading partners. WTO did not bind tariffs low enough to result in opening economies around the world for freer trade due to a convoluted system of concessions and exemptions. The large US trade deficits were the consequence of an unfair trading regime where so many countries have taken advantage of the openness of the largest single country market without reciprocating with their own openness. These reciprocal tariffs are designed to reverse this course of trade by insisting on reciprocal openness.

But there are naysayers to this argument. First, leading trade economists have argued that a trade deficit is not a sign of weakness nor is a trade surplus a sign of strength. Belgian economist Robert Triffin once argued that the US runs trade deficits not because it imports more than it exports; but it imports more because it must export US Treasuries to generate surplus in its capital account to counter the negative trade balance. Second, the idea of reversing trade deficits with countries and regions around the world is in complete defiance of the logic of comparative advantage. It is unlikely to produce the result intended, according to leading trade economists.

Negotiating Leverage. The US Government believes that reciprocal tariffs serve as a tool for leverage in trade negotiations. So impose tariffs to bring trading partners to the negotiating table and secure better deals (e.g., revised NAFTA led to USMCA). Each country will have to negotiate one-on-one if they want lower tariffs.

These tariffs have rocked the world economy. Expect subsequent negotiations and tit-for-tat tariffs that will continue to infuse turbulence and uncertainty in global trade and investment for some time. Ostensibly, the US has invoked “economic emergency” and “national security” Article XXI exception to WTO rules. In practice, it is by far the most appalling attack yet on the global rules-based trade order. The modus vivendi smacks of “our way or the highway” logic imposed on trading partners, with an offer of coming to the negotiating table.

WHAT LEADING AMERICAN TRADE ECONOMISTS SAY: Nobel Laureate economist Paul Krugman warns that such actions could lead to increased prices for consumers and potential job losses, thereby harming the U.S. economy. Leading American trade economist Dani Rodrik summarises the situation bluntly: broad tariffs “hurt the US economy, and more so than they do other economies”Jeffrey Sachs, a globally renowned economist at Columbia University, argues that these tariffs are counterproductive and detrimental to both the U.S. and global economies.

RECIPROCAL TARIFFS ON BANGLADESH AND COMPETITORS: It may be difficult to find a method in these tariff shenanigans. But there is. A baseline across-the-board reciprocal tariff of 10 per cent signifies a presumption of universal imbalance in international trade with USA. It could be the offsetting tariff for the presumption that the US dollar being a reserve currency it is perennially over-valued giving all other trading partners a competitive edge to start with. The other differential reciprocal tariffs on “worst trade offenders” aim at reducing the glaring trade deficits that are perceived as the result of unfair trade practices. In complete disregard of Bangladesh’s strong competitiveness in labour-intensive apparel exports, it has been included in that list given that its trade surplus with US, though modest in relative terms, is rising over time as it gains market share in the US over China. Meanwhile, the US Trade Representative (USTR) in its 2025 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers has identified Bangladesh’s trade regime as non-transparent and restrictive on account of its tariffs, loose management of Intellectual Property (IP) regulations, and other non-tariff barriers including corrupt practices.

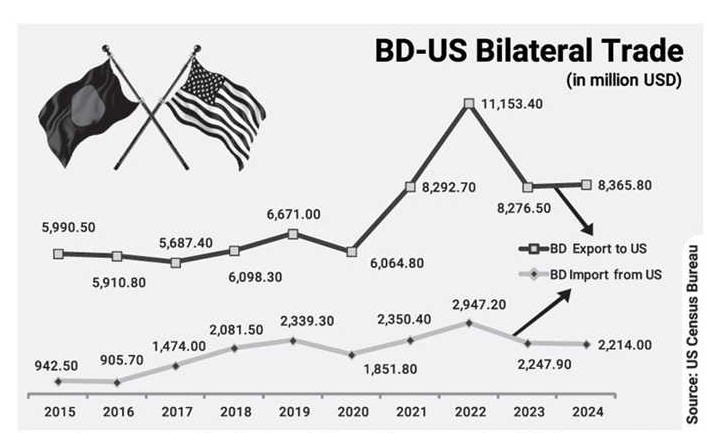

All Bangladesh exports to USA (including RMG) will now be subject to an across-the-board 37 per cent tariff over and above pre-existing rates because US Govt has estimated that US exports to Bangladesh face an average of tariffs and tariff-equivalent trade barriers at 74 per cent. The US strategy has been to impose tariffs at roughly 50 per cent of tariffs US exports face in these countries. Rather than searching for actual Bangladesh tariffs the ad hoc computation is as follows: In 2024, Bangladesh exports to US was $8.4 billion, the trade surplus with US was $6.2 billion, so the ratio (6.2/8.4) equals 74 per cent. One-half of that is 37 per cent, the additional duty applicable to imports from Bangladesh.

Our estimates show current Bangladesh average tariffs on imports from US are 26 per cent (nominal tariffs) and 54 per cent (total trade taxes). But total trade taxes on automobiles imports from US average 115 per cent, and 445 per cent on alcoholic beverages, though cotton imports have zero tariffs and the highest imports (Ferrous metals and scrap) have 1.5 per cent tariff equivalent; most machineries are subject to the lowest tariffs (1-3 per cent). In FY2024, Bangladesh imported some $2.2 billion from USA collecting customs revenue of some $215 million.

Since reciprocal tariffs on countries are not uniform relative competitiveness of Bangladesh exports will be affected by whatever tariff differential remains once the proposed tariffs are in effect. Competitor nations that are subject to lower reciprocal tariffs than that on Bangladesh will gain competitive advantage. Therefore, it is of utmost importance for Bangladesh to negotiate reduction in these tariffs so that they stand below or equal to the ultimate tariffs of competitors. Note that Vietnam, Cambodia, and India have all started the negotiation process to roll back some of the reciprocal tariffs. Bangladesh cannot afford to fall behind. Our understanding is that Bangladesh has already engaged with US authorities for effectively moderating the shock. Other RMG competitor countries face the following additional tariffs: China (20+34=54 per cent), Cambodia (49 per cent), Vietnam (46 per cent), Sri Lanka (44 per cent), Pakistan (29 per cent), India (26 per cent).

Strategic Response to proposed Reciprocal Tariffs. Since Bangladesh runs a lower trade surplus with US (approx. $6 billion), compared to China ($300B), Vietnam ($123B), India ($49B), and as US imports mostly low-value products (RMG, rather than electronic or high-tech products) from Bangladesh, strategic negotiations could yield positive results. Lacking any meaningful market power, taking a tit-for-tat tariff stance will be unwise. There is no scope for retaliatory tariffs.

The negotiating stance should be to reduce US specific import tariffs on products of export interest to the US. Such items include agricultural products, machineries, semiconductor parts and components, automobiles, etc. Quite a few of these imports have little revenue implications. Tariffs on cotton (0 per cent) and scrap metals (1.5 per cent), products that constitute the highest import items from US, are already low, so should not raise any issues. Tariffs on non-RMG exports to US (e.g. footwear) will have to be reduced substantially to meet US demands on the one hand, reduce anti-export bias on the other, and incentivize exports to US.

Though setting discriminatory tariffs on a single country violates the MFN principle of WTO, these US tariffs could soon be dubbed by all as a “global economic emergency”. So, negotiating countries might invoke the same “economic emergency” or “national security” clause for setting specific rates on US imports, unless this could be used in Bangladesh as an opportunity for rationalizing and scaling down MFN tariffs overall. If US negotiators seek “tariff bindings” of their own this could force overall reduction in tariff bindings of Bangladesh in WTO – a prickly issue no less.

Bangladesh’s exporters may retain their relative competitiveness through a negotiated resolution, but the overall impact remains uncertain due to reduced trade flows as tit-for-tat tariffs of China or EU will raise prices and dampen demand worldwide. China is hit hard as it is now subject to 54 per cent additional tariffs because of the 20 per cent tariffs already slapped on its imports earlier. Bangladesh could benefit from trade diversion away from China as global buyers seek alternative suppliers. Bangladesh has the relative advantages of cost competitiveness, high production capacities, increasing environmental compliance, and reliable and dynamic entrepreneurs.

Nevertheless, various estimates suggest global GDP could shrink by about 1 per cent and trade by 3 per cent. And Asia could be hard hit by an intensified US-China trade war and the higher rates of reciprocal tariffs, if not rolled back after negotiations. Malaysia, which is deeply integrated with US and China through GVC supply chains, appears to be especially hard hit as is most of the ASEAN countries that thrived on GVC trade.

Finally, RMG exporters of Bangladesh need to work with buyers on ways to share the cost escalation from tariffs through adjustment of prices, within the constraints of very limited market power for Bangladeshi suppliers.

END NOTE: To conclude, the US scheme of reciprocal tariffs looks like a sledgehammer unleashed on a glass house — a frontal attack on the world trade order. Make no mistake, these history making tariffs have already unleashed turbulence on world trade and the global economy and the impacts are unlikely to die down soon if the proposed reciprocal tariffs prevail in the end. Indications of that can be discerned from the rout of the stock markets in US and around the world. Trillions of dollars worth of market capitalization have been shaved off equity markets in US and around the world. While EU President Ursula von der Leyen acknowledged that the prevailing multilateral trade regime did have elements of unfairness resulting from differential levels of trade openness, she warned that reaching for tariffs as the first resort would only make matters worse and lead to dire consequences for the world economy. “It’s the biggest lurch into protectionism by America since the Great Depression of the 1930s”, she said. EU is planning countermeasures.

But Bangladesh’s optimal choice in these turbulent times is to move with a cool head, strategise damage control, and resort to bilateral negotiations to get out of this mess.

Dr Zaidi Sattar is Founder Chairman, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI). He can be reached at zaidisattar@gmail.com

https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/views/making-sense-of-the-tariff-shenanigans