Among the constituent macroeconomic policies, trade policy in Bangladesh typically draws the least attention, until it does. Since 2022, though the focus has been largely on trade and current account deficits and the financial account of the balance of payments (BOP), researchers on trade policy have drawn attention to the mismanagement of exchange rate and the high protective tariffs as among the sources of macroeconomic instability. The link between trade policy and Bangladesh development in the short-, medium-, and long-term is unambiguous.

Trade has been a handmaiden of Bangladesh development. After two decades of prevarication, in the 1990s policymakers in Bangladesh switched gear and changed trade policy stance, drawing from the new development paradigm – growth driven by exports.

The new trade orientation soon became the driver of rapid growth and job creation. Over the past few decades, Bangladesh has emerged as a success story of development, propelled by a thriving manufacturing sector, rapid urbanisation, and notable progress in human development indicators. Now, as we all know, this progress came at the expense of deep governance failures, institutionalised corruption, and rising inequalities, that will undermine future progress unless the root causes of this malaise are addressed swiftly and radically. Having entered the Lower Middle-Income Country (LMIC) group in 2015, Bangladesh faces an evolving global trade dynamics amid geopolitical fragmentation, deglobalisation, and rising protectionism. These present both challenges and opportunities in this evolving global phenomenon.

With the impending graduation from Least Developed Country (LDC) status, trade policy has become more crucial than ever. Historically a pillar of economic growth and poverty reduction, trade policy must now be reimagined to navigate the loss of preferential market access and sustain Bangladesh’s growth trajectory. This necessitates a strategic and adaptive approach to maintain competitiveness and strengthen the nation’s position in global trade.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND EVOLUTION: Since its independence in 1971, Bangladesh’s trade policy has undergone transformative shifts. Historically, trade strategies have generally followed two paradigms: inward-looking import substitution (IS) and outward-looking export orientation.

Post-independence, Bangladesh’s priority agenda centred on addressing widespread poverty and fuelling economic recovery, primarily through domestic-oriented policies backed by donor assistance. With zero foreign exchange reserves and the urgent need to import essential goods, high tariffs and import controls were implemented to conserve foreign exchange and prioritise the domestic market. However, while these measures provided short-term relief, they ultimately constrained economic growth and hindered long-term competitiveness.

The 1990s marked a significant turning point in Bangladesh’s trade policy. Bangladesh adopted radical structural adjustments with technical support from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), ushering in sharp tariff reductions, extensive import liberalisation, and a shift from fixed to flexible exchange rates, along with limited current account convertibility and elimination of the license raj. These reforms, coupled with market orientation and investment deregulation, not only restored macroeconomic stability but also laid the foundation for an export-led growth strategy. This policy shift spurred rapid industrial expansion, job creation, and poverty reduction, earning Bangladesh recognition as one of the “globalisers” among developing nations propelling significant gains in income growth and poverty alleviation.

A key success story of this outward-oriented approach was the rise of the ready-made garments (RMG) sector. Benefiting from duty-free input schemes and access to global markets, the RMG industry became the backbone of Bangladesh’s economy, growing from just 3.9 per cent of total exports in 1983-84 to 75 per cent by 1999-2000 (BGMEA 2019). This sector not only generated substantial foreign exchange but also created millions of jobs, particularly for women, driving significant inclusive growth. By successfully integrating into global value chains (GVCs), Bangladesh emerged as a key player in the international textile and apparel market, eventually becoming second largest exporter of apparel after China.

It was the trade liberalisation and market-oriented reforms of the 1990s that laid the foundation for sustained economic dynamism, positioning Bangladesh as a vibrant and competitive economy on the global stage.

CURRENT STATE OF TRADE POLICY: International trade has been a key driver of Bangladesh’s remarkable economic transformation over the past three decades. Alongside industrial growth, trade has played a pivotal role in shaping the country’s development trajectory. The contribution of industry to GDP has surged from under 10 per cent in 1972 to 37 per cent today, with Bangladesh yet to enter the de-industrialisation phase. International trade volumes have skyrocketed, reaching $130 billion in 2022, up from just $6 billion in 1990.

The trade liberalisation reforms of the 1990s, though not fully comprehensive, generated enough momentum to stimulate export-oriented manufacturing growth, job creation, and poverty reduction for the next two decades, and the momentum has merely weakened in the post-Covid era The economic impact of these reforms is reflected in rising decadal GDP growth rates: 4.8 per cent during FY 1991-2000, 5.9 per cent in FY 2001-2010, and 7.2 per cent in FY 2011-2019. This growth has translated into significant poverty reduction. The moderate poverty rate, which stood at 60 per cent in 1990, nearly halved to 31.5 per cent by 2010, and further declined to 18.7 per cent in 2022 (according to Household Income and Expenditure Survey, 2022) – a highly effective sign of inclusive growth.

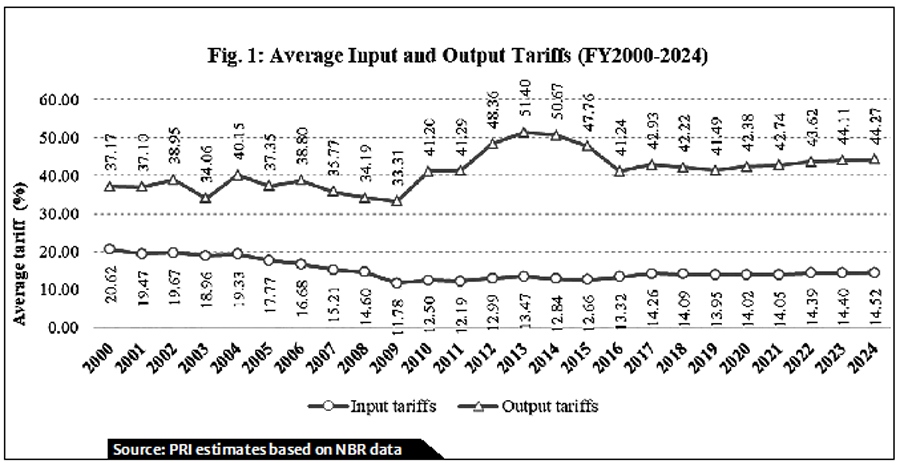

Despite these achievements, Bangladesh’s current trade policy presents a unique dualistic structure. While the 100 per cent export-oriented RMG sector benefits from a liberal trade regime (near free trade channel), non-RMG exports face restrictive and protectionist barriers. This trade policy dualism highlights a complex trade environment shaped by domestic policy choices that create a protected domestic market which typically yields higher profitability than exports, thus discouraging non-RMG exports and, consequently, stifling export diversification. This trade policy obfuscation is demonstrated in the following chart (Fig.1).

The government keeps the tariffs on inputs lower than the tariffs on outputs/finished goods, so that the domestics producers get access to lower priced imports of raw materials. The higher output tariffs ensure that the competition from foreign consumer goods are lower and hence, the domestic producers retain an advantage in the domestic market. The values of average input tariffs have remained fairly stable post-2009 ranging from 12 – 15 per cent, while output tariffs are modestly on the rise. Effective tariff protection – outcome of changes in output and input tariffs – has been on the rise as input tariffs fell but output tariffs rose. Notably, the divergence between input and output tariffs fosters Anti-export bias, favouring domestic sales over exports. This phenomenon raises profitability of import substitute production and undermines incentives for non-RMG exports whose producers find the domestic market significantly more attractive!

Export diversification is imperative for sustaining growth. Bangladesh must broaden its export basket to include intermediate goods and deepen its integration into regional value chains (RVCs), particularly in East Asia. Apart from the tariff barrier, restrictive trade practices also divert much-needed FDI in non-RMG manufactures away from our shores. Addressing these challenges will be essential for sustaining inclusive growth and fostering greater diversification within Bangladesh’s export portfolio.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR TRADE POLICY: Bangladesh’s trade policy is at a pivotal juncture, moulded by evolving global geopolitical and economic challenges that necessitate strategic shifts to sustain growth and competitiveness. Geopolitical fragmentation, rising protectionism, homeland economics and strategic autonomy, and US-China decoupling are disrupting global trade dynamics, threatening the efficiency dividends of globalisation and GVC integration. However, these shifts also create new opportunities, particularly for Bangladesh’s RMG sector, as production orders increasingly shift from China. McKinsey Global reports that at least $100 billion out of the $625 billion apparel market in 2030, will move away from China, in light of shifting geopolitical order, on top of the already rising wage costs in China.

Restoring macroeconomic stability is critical for navigating these challenges. Priority measures include curbing inflation, stabilising the exchange rate, and rebuilding foreign exchange reserves. Strategic tariff adjustments can help ease inflationary pressures while facilitating trade. Enhancing market access through free trade agreements (FTAs) and Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPAs) are equally essential for bolstering Bangladesh’s post-LDC graduation competitiveness.

As Bangladesh prepares for LDC graduation by 2026, it faces the challenge of preference erosion. The phasing out of international support measures (ISMs) will diminish preferential market access, impacting export competitiveness. To navigate this transition successfully, Bangladesh must undertake a strategic overhaul of its trade policy. Attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) will be crucial, requiring improvements in the investment climate through streamlined regulations, one-stop window service, enhanced infrastructure, and competitive incentives. Proactive and forward-looking trade strategies will enable Bangladesh to navigate these challenges and sustain its economic momentum on the global stage.

STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE TRADE POLICY: To navigate the challenges, Bangladesh needs to consider a new round of strategic trade policy reforms. This includes enhancing rationalisation of tariff protection, trade facilitation measures, diversifying export products and markets, reducing trade costs via digitization of international trade, and strengthening regional trade agreements to mitigate risks associated with global trade uncertainties, and position the country for sustainable growth.

Tariff rationalisation and Exchange rate flexibility

- First, the anti-export bias of trade policy must be eliminated by rationalising tariff protection through import duties, regulatory duties, and supplementary duties. Exports, particularly non-RMG exports, must be incentivised by scaling down protective tariffs and achieving neutrality between profitability of exports and domestic sales of import substitutes. This will pave the way for export diversification and compliance with WTO regulations. Moreover, prompt and effective implementation of the National Tariff Policy 2023 must be ensured. The policy already addresses some of the issues of anti-export bias, rationalisation of tariffs and consumer welfare. Therefore, it is crucial those suggestions are readily executed.

- Secondly, the exchange rate, being a pivotal pricing instrument for exports, must be governed with a flexible management approach to ensure export competitiveness through a market-determined exchange rate. There should be no scope for any appreciation of the real effective exchange rate, a key indicator of export competitiveness.

Export Diversification strategy. The current tariff regime is a major obstacle to export diversification. While the 100 per cent export-oriented RMG sector operates in a duty-free environment, diversifying the export basket requires giving non-RMG export the same duty-free environment and neutrality of incentives between exports and domestic sales. Bangladesh can diversify its product range by venturing into higher-value garment categories such as apparel of man-made fibre and luxury clothing, leather and non-leather footwear. Assembly and manufacturing of electronic goods, and expand its ICT sector to boost software and IT services. Furthermore, the agricultural sector presents untapped opportunities – modernising agricultural practices, increasing productivity, and diversifying crops can increase exports of fruits, vegetables, and value-added products such as organic and processed foods (agro-processing). The pharmaceutical industry also holds significant growth potential. By producing generic drugs and obtaining international certifications, Bangladesh can access lucrative global markets.

Promoting Trade Facilitation. Trade facilitation is required to boost Bangladesh’s competitiveness. Key measures include simplifying trade procedures, reducing bureaucratic hurdles, and modernising customs. These reforms can lower transaction costs and enhance the global competitiveness of Bangladesh’s exports. Additionally, investing in transport, ports, and logistics infrastructure will further improve trade efficiency. Digitalising customs processes is another crucial step in reducing trade transaction costs, streamlining operations, and making Bangladesh’s trade environment more efficient.

Enhancing Regional Value Chain Integration and Market Diversification. To accelerate trade and export growth, Bangladesh should focus on integrating more deeply into regional value chains (RVCs). This involves greater trade openness, boosting trade in intermediate goods, facilitating smoother movement of raw materials, and creating synergies with neighbouring economies. The development of regional partnerships will enhance Bangladesh’s position in global value chains, ensuring greater market access and industrial growth.

To navigate the evolving global trade landscape, Bangladesh should focus on market diversification. As a potential “connector” country between different geopolitical blocs, Bangladesh can seize opportunities to serve as an intermediary for trade, positioning itself strategically in emerging markets. This approach will not only mitigate risks but also create new avenues for growth.

Pursuing Trade Agreements. Engaging in trade agreements is essential for securing market access and diversifying Bangladesh’s trade portfolio. The country must pursue greater trade openness and create favourable conditions for export-seeking foreign direct investment (FDI). Signing more free trade agreements (FTAs) with larger economies or regional blocs is critical. Rationalizing tariffs and eliminating the anti-export bias of incentives will help Bangladesh leverage its strategic location and competitive labor force to position itself as a hub for regional trade.

Investing in Innovation and Quality. To transition from a price-driven competitiveness model to one focused on quality and innovation, Bangladesh must invest in innovation and elevate the quality of its exports. Increasing investments in health and education, with a focus on workforce upskilling, is key to preparing the labor force for high-tech industries and fostering innovation. Support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), alongside investments in infrastructure, will further catalyse this diversification.

Adapting to Global Financial Fragmentation. As global trade faces financial fragmentation, particularly the shift away from US dollar dominance in trade payments, Bangladesh must remain agile and responsive to this shift. Exploring alternative payment systems and diversifying financial partnerships will help the country maintain its position in the global trade arena. Strategic economic diplomacy will be essential to tread this emerging landscape with utmost circumspection.

Trade Policy as a tool for Sustainable Development. As Bangladesh aims to transition to an upper-middle-income economy, integrating sustainability into its trade policies is crucial for long-term growth. This includes promoting green exports, incentivising eco-friendly production, and supporting circular economy practices. Lowering tariffs on clean energy technologies can accelerate the shift to renewable energy. Additionally, aligning with global environmental and labour standards ensures continued access to key markets, especially in regions with strict regulations like the European Union. Trade policy should also empower SMEs and rural producers, fostering inclusive growth. By prioritising sustainability, Bangladesh can build a competitive economy that safeguards both its environment and its future development.

CONCLUSION: Trade policy is not merely a tool for economic growth; it is a critical pathway for Bangladesh’s development. As the country moves away from LDC status, it must adopt a forward-looking open trade strategy that tackles current challenges, while seizing emerging opportunities. Through trade policy reforms, export diversification, and strategic agreements, Bangladesh can sustain its development momentum and accelerate towards achieving its goal of becoming an upper-middle-income country by early 2030s. The future of Bangladesh’s development depends on its ability to navigate global trade complexities with strategic foresight and compatible economic diplomacy.

Dr Zaidi Sattar is Founder Chairman and CEO of Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI) where Samah Majid is a Research Associate. zaidisattar@gmail.com

https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/trade-policy-a-strategic-input-in-bangladesh-development