This deep reduction in imports has hurt both investments and GDP growth

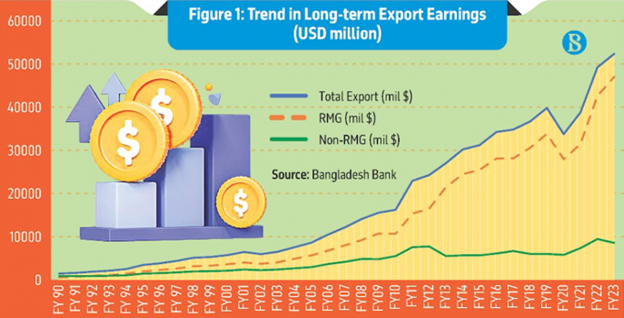

Bangladesh has secured outstanding long-term export performance, growing from a mere USD 1.5 billion in FY1990 to an astounding USD 52.3 billion in FY2023 (Figure 1). On average, exports grew by an amazing 11.3% per year over a 33-year period. This export-orientation of the development strategy has served Bangladesh well, contributing handsomely to GDP growth, employment and poverty reduction.

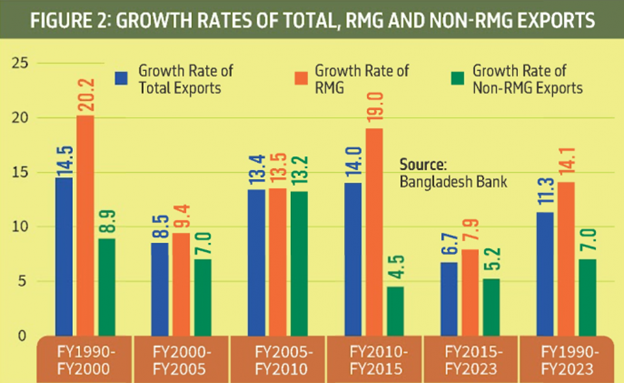

While the long-term highly favorable export trend is good news and speaks well to the Bangladesh potential, there are two major concerns. First, much of the export expansion has come from the ready-made garments (RMG) sector; non-RMG exports have grown relatively slowly. And second, export growth has slowed considerably over the past several years. Thus, exports grew by a mere 6.7% between FY2015-FY2023 as compared with 13% between FY1990 and FY2015.

The import surge of FY2022 owing to global inflationary pressures put considerable stress on the balance of payments that saw the imposition of substantial trade and exchange controls to reduce imports. As a result, imports fell by 35% between FY2022 and the first half of FY2024. This deep reduction in imports has hurt both investments and GDP growth. The push for higher growth of exports has become critical to restore the recovery of imports needed to support the momentum for investment and GDP growth.

The heavy concentration of the Bangladesh export basket on one commodity group and the associated absence of export diversification has posed a major challenge for strengthening export performance. While the global RMG market is very large and Bangladesh has scope for increasing its market share, the government now understands that export diversification is essential to accelerate the expansion of exports and eliminate all kinds of import controls.

Research done at the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI) shows that in FY2021 Bangladesh exported some 1393 non-RMG product, of which 346 items registered export values of USD 1 million or above. Among these, Bangladesh has strong comparative advantage in 39% of the products and moderate comparative advantage in another 27% of the products. So, potential competitiveness of a large, diversified export basket is not an issue.

The reason that this potential has not materialized in actual sustained export growth for most of the products is because of the large anti-export bias of government policy, especially related to trade policy. On the trade policy front, there is huge protection accorded to import substitutes through a range of tariffs and para-tariffs that make production for domestic market much more attractive than exports. This anti-export bias of trade policy is not well understood in policy making. The simplistic argument used by advocates of trade protection is that trade protection promotes import substitution and is therefore good for balance of payments management and GDP growth. Why should it discourage exports?

Quite apart from the loss of consumer welfare due to the high cost of domestic production through a trade-protection regime, the fallacy in the argument is that it misses a fundamental principle of economics that in a market economy domestic investment and production decisions are guided by relative profitability based on price signals. An investor will invest and produce for export markets if the relative profitability from exporting is higher than production for the domestic market. The profitability of exports depends upon the world price, the exchange rate and commercial policies like export subsidy. On the other hand, the profitability of the local market is determined by the world price, the exchange rate and import tariffs. If the rate of import tariff exceeds the rate of export subsidy, then the domestic price of the product will exceed the export price by the differential between the import tariff and the export subsidy. The underlying trade policy regime involving the tariff and subsidy will then impart an anti-export bias. More generally, the higher the average rate of tariff relative to the average rate of subsidy, the higher will be the anti-export bias of trade policy.

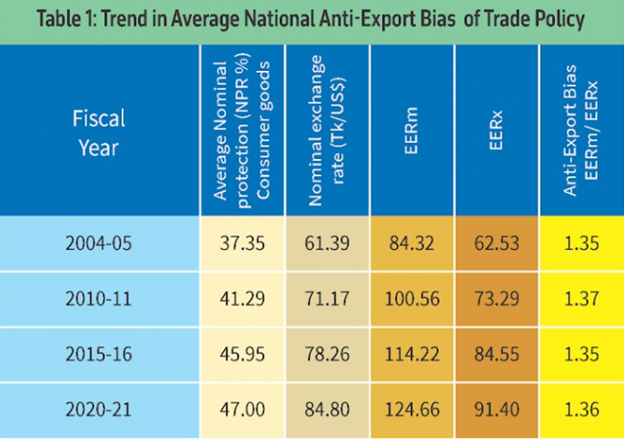

For a small trading country like Bangladesh, under free trade the price of a product in the exports and domestic markets are the same as determined by world prices. But these prices will diverge owing to import tariffs and export subsidies. The anti-export bias of trade policy can be estimated by using the ratio of the exchange rate augmented by the average tariff rate in the numerator, and the exchange rate augmented by the average subsidy rate in the denominator. That is: exchange rate x (1+the average tariff rate) / exchange rate x (1+ average subsidy rate). The numerator reflects the effective exchange rate for import substitutes (EERm) and the denominator represents the effective exchange rate for exports (EERx).

If the rate of tariff is the same as the rate of subsidy, then the value of the ratio will be one and trade policy can be considered as neutral in terms of the incentive structure for exports versus domestic production. If, however, the average rate of tariff exceeds the average rate of subsidy, than the ratio will exceed one suggesting that the incentive structure is biased in favor of domestic production and against exports. In this situation, the investors would like to invest and produce for the domestic market rather than exports because it is more profitable to produce for the domestic market. The higher is the rate of tariff protection relative to export subsidy, the higher will be the value of the ratio greater than one, and the higher will be the anti-export bias of trade policy.

The PRI has estimated the anti-export bias of trade policy in the context of a recent study done for the government (Comparative Advantage and Export Diversification Prospects: Policy Imperatives for Bangladesh, 2023. Report submitted to the Economic Relations Division, Ministry of Finance). This is shown in Table 1.

As is obvious, the average rate of export subsidy is very modest, rising from 1.9% in FY2005 to 7.8% in FY2021. As compared to this, the average nominal rate of protection (includes customs duties, and par tariffs such as regulatory and supplementary duties) is large and has continued to grow (from 37% to 47% over the same periods). Overall, the trade policy has continued to impart substantial anti-export bias due to large trade protection, thereby providing incentives for domestic production and discouraging exports.

At the product specific level, the RMG sector is the most important exception. Because it is 100 percent export oriented and it enjoys duty-free access for all its imported inputs, it does not suffer from trade protection bias. Instead, it enjoys some subsidies and as such it has negative anti-export bias. The absence of anti-export bias is a key determinant of its phenomenal export success. On the other hand, important non-RMG exports like shoes, other leather products, jute goods, ceramics, home textiles and light engineering products all suffer from substantial anti-export bias that constrains their dynamism.

The elimination of the anti-export bias of trade policy is of highest priority. Without this reform, the ability to diversify exports will suffer. Trying to overcome this bias through export subsidies will be counter productive because of the high fiscal cost of such a policy in a heavily constrained resource environment.

Export diversification will also require a market-based and flexible exchange rate, additional efforts to strengthen market access through Free Trade Agreements, comply with safety and environmental regulations, improve trade logistics through deregulation and investments in port and transport networks, promote export oriented FDI by lowering the cost of doing business, and strengthen labor skills through investment in education and training.

Sadiq Ahmed, Vice Chairman, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh

https://www.tbsnews.net/analysis/anti-export-bias-trade-policy-811174