An important step for calming foreign exchange market was to curb excess demand by tightening of imports. That seems to be working at a time when exports and remittances are looking to be on track for a good year.

At the close of fiscal year 2021-22 (FY22) the economy experienced three major economic shocks from the outside world: first came the post-pandemic supply chain disruption that constrained global supplies and raised costs; next was the Russia-Ukraine war, which also produced the third shock, namely, the spike in food and oil prices that fuelled a global inflation and also triggered a rise in food and energy prices in Bangladesh.

The combined effect of these three shocks rattled the global economy after February 2022. Bangladesh economy could not escape the ramifications of this debacle. Despite building strong foundations for macroeconomic stability over a period of 25 years, there appeared cracks in the system entirely due to external developments on which Bangladesh had no control. Fiscal year 22 was turning out to be a good year for the economy of Bangladesh. Until end December 2021, exports were surging at a record clip of 35 per cent, but imports were surging as well, at a rate of 50 per cent. The last fiscal year ended in June with exports up 35 per cent and imports at 36 per cent (declining from the 50 per cent clip due to high import prices and tightening of import and foreign exchange utilisation procedures in the closing months). Such episodes of a combined surge of exports and imports are not unknown in Bangladesh’s trade history. It occurred in 1995 (exports surged 30 per cent along with imports at 41 per cent) and in 2011 (exports surged 42 per cent, with imports up 52 per cent). Why imports surge much greater than exports contemporaneously is a matter for careful research instead of making off-the-cuff judgments related to malfeasance. By the way, in all these episodes, manufacturing production jumped in the same or subsequent years, including this time around!

Our import bill typically is higher than export receipts by some $10-20 billion because import requirements rise with a fast-growing economy resulting in trade deficits which also tend to rise with growth. PRI research on import categories show that in the past decade, consumer goods make up only 18 per cent of all imports, the rest (82 per cent) is comprised of basic raw materials, intermediate and capital goods, all headed for the productive sectors of the economy, particularly industry. It is notable that Bangladesh is primarily an exporter of manufacturing goods (95 per cent of exports) which require imported inputs, unlike primary exports (like jute, cotton, oil) which are extracted from the soil. Consequently, a surge in exports automatically results in a surge in imports. There is no episode of an export surge that is not accompanied by an import surge. The label of an “import dependent” economy should not be taken to describe a hapless situation because industrialisation begets import reliance. But there is nothing bad about that. China, which is known as an export powerhouse and is the largest exporter in the world (exports of over $3 trillion) is also the second largest importer of the world (over $2 trillion).

Such export-import linked surges also lead to a spike in the trade deficit which needs to be financed. Thankfully, Bangladesh has a ready source of import financing besides exports – export of factor services, namely, remittance from migrant workers. Rising remittances covered much of the trade deficit for most years since 2001, leaving modest surpluses in our current account, except in the past five years which experienced modest but sustained current account deficits (CAD). That is why the spike of 36 per cent in imports which jumped to a whopping $82 billion led to a spike in the CAD causing huge pressure on the Balance of Payments (BOP) and the exchange rate. It turned out that the efforts of Bangladesh Bank to maintain the Taka-US$ exchange rate fixed at around Tk.86/US$ by unloading foreign exchange in the market was no longer tenable. So the exchange rate had to be floated resulting in a depreciation of about 11 per cent reaching Tk.95/US$. It was almost like letting the Gein out of the bottle and the foreign exchange market experienced volatility fuelled by speculation of all sorts, coming at a time that Sri Lankan economy went literally bankrupt under the weight of huge external debts they could not service.

Bangladesh is nowhere near the Sri Lankan boat. Debt Sustainability Analysis recently done by World Bank-IMF showed Bangladesh debt situation in a comfortable zone. With so much speculation about Bangladesh going the Sri Lanka way originating from the ‘bad-news-biased’ news reports, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had to come out with a statement to the press reconfirming that Bangladesh debt situation was indeed comfortable and Bangladesh is negotiating for IMF loan as a pre-emptive measure to take advantage of IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) Fund for a modest loan to bolster its external position to withstand any further deterioration in external conditions.

SOURCE OF THE PROBLEM IS IMPORT SURGE: It is the import surge that was the source of the exchange rate (ER) problem. The import surge was linked primarily to the export surge together with the global price spike in food and energy. The ER is simply the price of foreign exchange (e.g. US$). It is determined by the demand and supply of foreign exchange. The demand comes from imports of goods and services and the supply comes from exports of goods and services, in addition to official development assistance (ODA) received from multilateral and bilateral institutions (like WB, IMF), and inflows of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). The import surge created an excess demand situation putting pressure on the exchange rate to depreciate, i.e. Taka price of US$ to rise. Though Bangladesh moved into the ‘floating’ exchange rate regime back in 2003, the actual practice was a ‘managed float’ – perhaps too much managed to make it look almost like a ‘fixed’ exchange rate system. For instance, the Tk/US$ rate remained at Tk.85-86 for nearly three years until May 2022. After drawing down some $7 billion from FE reserves BB had to let the ER float until it reached the bank rate of Tk.95/US$, where it rests now. Whether it is going to stay there as the equilibrium market rate is difficult to say.

An equilibrium market exchange rate is where demand and supply equilibrate. In a dynamic economy with exports-imports transacted on a daily basis, there is no textbook formula that can tell us what it is. The BB judgment call that, at Tk.95/US$, it can keep demand-supply approaching equilibrium, could be right provided any excess demand over supply of foreign exchange is eliminated by, as we see, effective administrative measures to curb import demand. If excess demand persists with outflows far exceeding inflows of FE, that means the ER would have to depreciate further.

However, there are positive signs of demand-supply gap closing. The price effect is already working to curb import demand: rise in international prices of food, energy, and other industrial products plus 11 per cent depreciation of exchange rate which raises Taka import price by another 11 per cent. Overall, the import price effect together with recent administrative curbs are proving effective to restrain imports in the near term which is showing up in the record of monthly LC opening which had a sharp reduction of 10 per cent in June and that trend is persisting according to reports coming out of Bangladesh Bank (BB).

If the source of the current volatility in the foreign exchange market is the excess demand originating from imports, curbing imports is the right solution, regardless of whether it comes from price spikes or administrative curbs. With exports and remittances on track the challenge is to restrict imports at $80 billion or less. If the current policy is effective, it gives us hope that in the current fiscal year, 2023, the excess demand pressure will abate and the foreign exchange market will stabilize, sooner rather than later. We will know in about three months. Once the demand-supply gap is eliminated, exchange rate volatility will disappear and with it all the rumour mongering and speculation too.

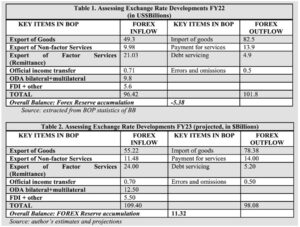

The tables present a comparative picture of what happened in terms of demand (outflow) and supply (inflow) of foreign exchange in FY22 versus what is expected to happen as a result of exchange rate depreciation as well as administrative curbs on imports of consumer goods. Note that import curbs are not targeting imports of industrial raw materials, intermediate or capital goods so that the superior export performance (including industrial and agricultural output) continues unabated. According to leading development economists, China is losing competitiveness on about $150 billion of its exports, some of which will be and is currently being diverted to Bangladesh and other Asian economies. More diversion is taking place due to US-China tensions and the strategic move towards “friend-shoring”. This creates an opportunity of a lifetime and Bangladesh should not miss it for anything.

Table-1 reveals the nature of the problem in FY22. Record merchandise imports of $82.5 billion outweighed even the export surge of 35% ($49.3 billion). But monthly inflows of FE from exports and remittances ($6.5 billion approximately) fell far short of demand from imports of goods and services (about $8 billion), putting excess demand pressure on the exchange rate that eventually led to the 11 per cent depreciation. That was still not enough to restrain demand enough to restore equilibrium and had to be supplemented by curbs on imports of luxury consumer goods alongside austerity measures curtailing power generation and hike in oil prices. The measures were taken in the last couple of months and some like power curtailment measures could be temporary with possible downward adjustment of oil prices as international prices decline.

As of now, the indications are that the austerity measures and administrative curbs are working and imports are on a downward path (Table-2). With exports growing at a 12 per cent clip and remittances responding to Taka depreciation with monthly inflows of over $2 billion, monthly FE inflows are running at about $0.5-1 billion ahead of FE outflows. If this trend is maintained we could end the year with a significant overall BOP surplus and more than $10 billion of accumulation in FE reserves, crossing $50 billion which will cover more than seven months of prospective imports – a very comfortable zone for FE reserves.

It is fair to conclude that the exchange market volatility that was experienced in the last couple of months was the result of FE demand (from imports) outstripping supply (from exports and remittances). The authorities have been spot on in identifying the problem – import surge. We need to watch the effectiveness of the austerity measures coupled with exchange rate management that allows the exchange rate to ‘float’ modestly and gradually, reminiscent of a ‘crawling peg’ regime. Thankfully, despite global economic slowdown, the prospects of basic garment exports remain strong (recall the Walmart effect) supplemented by the redirection of sourcing away from China. So, despite the 35% surge in exports in the past year, export performance in the current year, FY2023, is looking good for reasons just mentioned.

Let us face it. These are challenging times, for Bangladesh as well as other emerging market and developing economies (EMDE) around the world. In such times a little belt tightening is the sine qua non of appropriate adjustment. It might result in a modest growth slowdown as a cost for restoring stability. As long as there is adequate targeted support for the poor and deprived population such adjustment will have to be taken as part of the strategy for longer term stability and sustained growth momentum which appears quite feasible.

Dr Zaidi Sattar is Chairman, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI).