With Tk. 6.03 lac crore ( or Tk 6.03 trillion) of proposed expenditures, fully one-third of which is deficit-financed, the finance minister’s fiscal year 2021-22 (FY22) proposed budget is one of Bangladesh’s most ambitious and expansionary budgets in history. The budget is set to be approved at the parliament today (Wednesday). Expenditures in this budget will be 17 per cent higher than the revised FY21 budget and 28 per cent higher than actual expenditures in FY20. Given the need to extricate the economy from the Covid pandemic-induced slump, such an expansionary stance may indeed be necessary. However, the impact of government expenditures on the economy depends not only on their size, but also on how well they are allocated across functions and activities and how effectively they are spent.

On size, the biggest problem with our public expenditures is that they are extremely inadequate because they are structurally constrained by revenue shortfalls (See, “Meeting the Revenue Challenge,” by Ahmad Ahsan and Ramendra Basak, Financial Express, June 23, 2021). When countries develop, public expenditures grow faster than Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The richest market-based countries of the world are mixed economies because government expenditures make up between one-third (US, Japan) to nearly half of GDP (European Union countries). Closer to home, Vietnam spent 22 per cent of GDP and India 29 per cent in the past year. However, that does not convey the complete picture as their GDPs are larger. To get a more accurate picture of the inadequacy of our public expenditures, we calculate (Figure 1 below) the per-capita public spending in 2020 in comparable purchasing power parity international dollars. Vietnam and India spend more than three times and two and half times per capita, respectively, than Bangladesh.

Because our government can spend comparatively far less, we need extra care to ensure that these resources are well used. Bangladesh has traditionally done a good job of allocating expenditures in line with national priorities by investing in social sectors, rural infrastructure, roads, and, recently, crucial large-scale energy and transport projects. There are, however, critical emerging issues that need addressing.

EXPENDITURE ALLOCATIONS: On allocations, consider first the big-ticket items. Education and Technology (15.7 per cent of Budget), Finance Division (15 per cent), Transport (11.9 per cent), Interest Payments (11.4 per cent), Defence and Public Security (9.7 per cent) make up nearly two-thirds of expenditures. Social Welfare, Agriculture, Local Government and Rural Development, Energy, and Health each get about, give and take, 5 per cent of the Budget. A third of all these expenditures will be spent via the Annual Development Plan. Such a focus is welcome if it does not reduce necessary current expenditures and resources are effectively spent. There are issues about both aspects.

Two immediate points stand out. First, interest payments are nearly twice what we spend for high-priority sectors such as agriculture, energy, or health. So, unless we keep our primary deficits (deficit minus interest payments, budget to be 4 per cent of GDP) under control, debt will rise. Bangladesh has low debt, so debt stock is not a problem. But given our small fiscal space, interest payments can be a problem if they crowd out other essential expenditures.

The second is the massive allocation of Tk. 917.90 billion to the Finance Division – three and half times larger than the last pre-covid budget of FY20. The budget document explains in a footnote that this “Unexpected expenditure, subsidies and incentives are included in Operating Expenditure. Tk. 103.25 billion has been allocated for funding Public Private Partnership initiatives and export incentives”. One hopes that the bulk of this is reserve money for Covid-19 related medical expenditures. There needs to be clarity about how these reserves were spent in FY 2021.

In the rest of this article, we will touch on four points: (i) inadequate attention to fighting Covid-19; (ii) the costly neglect of Repairs and Maintenance; (iii) improving the Public Investment Programme Management; and (iv) suggestions to finance identified additional requirements and a plea to invest in woefully inadequate economic management activities.

FIGHTING COVID-19: The global war against the Coronavirus is continuing. More than 181 million people have been infected, and nearly four million have died. Most of the world’s people, including Bangladesh’s, remain unvaccinated and highly vulnerable. The Covid-19 virus has mutated now into the more transmissible Delta and other variants. Delta variant infections are currently growing by 70 per cent every week in the UK. Bangladesh, India’s neighbour, is now under dire threat from that variant. The country has just announced a 7-day national lockdown, although the NTAC has suggested a two-week lockdown.

Policymakers should realise by now that the so-called choice between “lives” vs. “livelihood” is fundamentally false. Without defeating the Covid-19, neither lives nor livelihoods will be safe. Economic recovery cannot take place when uncertainty and fear rule the country.

The proposed Health Sector budget seems somewhat unmindful of these truths. The Indian Central budget for fiscal 2021-22 has raised expenditures in the health sector by 137 per cent. We, on the other hand, have provided only a four per cent increase over last year. True, last year saw a hefty increase, the increase is about 87 per cent over two years, but the increase this year is too meagre.

India has administered 100 million vaccines over the past month – 3.30 million a day on average. Reportedly, our Finance Minister has talked of making provisions for 2.5 million vaccinations for Bangladeshis each month. That means, depending on whether he means 2.5 million complete vaccination or partial vaccination each month, it will take three to six years for Bangladeshis to get vaccinated. Such a delay is sure to create long-term damage to Bangladeshi lives and livelihoods.

The budget must aim to vaccinate 50 per cent of our population within the next fiscal year and the rest immunised by the end of 2022. Even if one assumes a high average of US$ 50 cost per complete vaccination, that will be about Tk. 350.62 billion or just over 1.0 per cent of GDP. It may be the case that the “Unexpected expenditures” allocated for the Finance division are for this purpose. But if so, let the government be transparent about it and use our fiscal and foreign exchange resources to start procuring the vaccine aggressively. Further, procurement can be done in stages, including buying “expansion options” for flexible contract. If vaccine prices decline, we can use the flexibility to take advantage of those prices then.

It will not be wise to depend on international aid and charity to get our vaccines. At this point, the global commitment for vaccines by the rich G7 countries amounts to only $ 1.0 billion against the IMF’s estimated need for $ 50 billion to vaccinate developing country populations. Even when funds start arriving, international agencies aware of Bangladesh’s foreign exchange reserves may choose not to prioritise our needs over desperate people elsewhere.

Vaccines are not all that will be needed. Medical personnel will have to be trained. The estimated 30,000 medical technologists available can be recruited – temporarily but with attractive salaries — to carry out vaccinations, testing, and provide hospital support. The Health sector will need to invest urgently in ICUs – perhaps double their number and make them available in all district hospitals and equip them with hi-flow oxygen supply. There will also be a need for medical equipment, especially those that supply oxygen, such as oxygen concentrators, CPAP/BiPAP machines, along with operational supplies include PPE. Even with vaccines, there will continue to be an urgent need for significantly increasing the number of Covid tests. For some odd reason, the Medical and Surgical Supplies budget for FY22 has been lowered compared to the revised Budget for last year.

Thus, in addition to the funding for vaccines, the government should consider increasing the allocation for the health sector from the Tk. 327.31 bilion (still less than 1.0 per cent of GDP) in the budget by half or TK. 160.00 billlion. The additional funds for financing treatment, protective and medical equipment, and testing against Covid-19 can be considered part of the economic recovery stimulus for the manufacturing sector and overall economy. Moreover, spending on equipment should be regarded as an essential long-term investment in Bangladeshis’ health care. To borrow a term from Climate Change economics, the investments discussed above are “No Regrets” expenditures: they will improve Bangladeshis’ long-term health care with or without Covid.

Yes, managing this increase in the budget will pose a challenge. For this, the Health Sector will need financial management and organisational support. Let the Army Medical Corps, the Engineering Corps, and medical students be mobilsed and put on standby should the need arise. As the Finance Secretary has indicated, the Finance Ministry and the CAG should provide technical assistance for the Health Ministry and other health agencies to plan, budget, and provide procurement, accounting and auditing, and implementation oversight.

Even with an accelerated pace, vaccination will take time, and we cannot let Variants infect people freely and mutate in the meantime. There may be the need for occasional lockdowns more or less all through the next fiscal year. To sustain those lockdowns, the government will need to provide relief for the bottom 40 per cent of the poor population and, as researchers say, the new poor. Assuming the policy will support keeping them above extreme poverty, the weekly cost for such support for 64 million people comes to about Tk. 30.12 billion. There should be plan for several such lockdowns by allocating Tk. 250.0 billion for relief. These are large sums.

But the likely benefit-costs of fighting Covid-19 are overwhelming. Imagine a chaotic fight and retreat against Covid 19 that overwhelms our health sector and shuts down the economy for months. Suppose in FY22 we face a Covid crisis similar to India’s in FY20 when the Indian economy lost almost 14 per cent of GDP (originally projected GDP – actual) in FY 2020. Suppose our losses are half that, our income loss will be about Tk. 2.42 trillion. And these are costs without taking into account the loss of human life and capital.

UNDERDEVELOPED COUNTRY SYNDROME: WHO CARES FOR REPAIRS AND MAINTENANCE?: A long-standing critical shortcoming of the Budget’s expenditure allocation is the extremely meagre amount allocated for repair and maintenance expenditures. The proposed public investment programme, measured by capital expenditures, is Tk. 2.36 trillion. Against that, the budget amount for Repairs and Maintenance is a paltry Tk. 118.10 billion, just shy of 5.0 per cent. These allocations support the underdeveloped country syndrome, pointed out sixty years ago by the insightful, famous American political economist John Kenneth Galbraith: underdeveloped countries fail to maintain their capital stock.

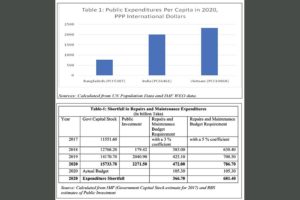

An exercise suggests Bangladesh is doing precisely that. Using IMF’s public capital stocks estimates for Bangladesh in 2017 with BBS investment data (see Table-1) suggests that Bangladesh’s publicly owned capital stock was around Tk. 15.73 trillion in 2020. Depending on the sector, coefficients for capital stock maintenance needs vary from 3.0 per cent (water reservoirs) to 4.0-6.0 per cent (Sewage, buildings), 5-10 per cent (Roads, electricity). Let us be economical and use 3.0 per cent and 5.0 per cent as coefficients.

As the last row in the table shows, the maintenance expenditure shortfall was between Tk. 367.0 billion to Tk 681.0 billion in FY20.

More research is needed. Evidence from the Roads and Highways survey from FY19 suggests that while their maintenance needs were around Tk. 107.0 billion that year, they were provided only Tk. 25.0 billion for that purpose. According to their estimate, only 50 per cent of the roads were in good conditions that year. As widely discussed in the press, such a lack of maintenance has led to the rapid deterioration of road conditions in highways and rural areas.

Unfortunately, similar data are not readily available in the power sector. However, it would seem that the rapid expansion of generation capacity has not been matched by maintenance expenditures for the power grid or aging sub-stations. If this is so and the situation persists, then the electricity supply will become unstable and not just unbalanced with demand as it is now. Thus, Bangladesh is at a point where even though it has close to 10,000 MW in excess capacity, it cannot transmit the power everywhere within the country and is compelled to import from India.

If repairs and maintenance are not adequately funded, the depreciation of our capital stock will be accelerated. Once countries fall significantly behind repairs and maintenance, they have a hard time catching up. Ultimately, huge costs of replacement have to be borne or not funded at all. It is widely agreed that the economic returns to Repairs and Maintenance are higher than the returns to many capital investment projects. Given these considerations, the government should consider a significant boost to the repairs and maintenance budget, perhaps using the lower expenditure shortfall.

When Prof. Mohammad Yunus started his work in Jobra Village in the mid-1970s, he found that villagers lived desperate lives because they depended on only one crop. Why was that? Because a BADC deep tube well installed only five years earlier had broken down. Despite pleas, the BADC responded they had no budget to repair it. So the people suffered. Then, honoring Professor Yunus’s request Chittagong’s D.C. and famed litterateur Hasnat Abdul Hye came to the rescue and persuaded BADC to repair the deep tube well. Life became better. What was true for Jobra village then is, even now, true for the whole country.

PUBLIC INVESTMENT PROGRAMME — A REVIEW HAS BECOME ESSENTIAL: The bright story about Bangladesh’s Budget is that development expenditures have doubled over the past five years. Capital expenditures increased by 28 per cent, according to revised FY 2021 estimates. Even if in nominal terms, this increase will be significant given the stable exchange rate and low inflation rate.

The sharp rise in the ADP and public investment raises the challenge to ensure its quality and value for money. A thorough review has long been pending, and the main point here is to urge the government to undertake such an exercise. There was such a review by the IMF – called Public Investment Management Assessment – in 2018, but the findings have not been released.

In the past few years, news reports and a 2015 World Bank study have identified several weaknesses in the public investment programme. Many projects and programmes were inadequately vetted before being included in the ADP. Most projects are not subject to rigorous costs-benefits analysis before approval. Not every project has to be based on such analysis. So, projects are often approved on more general, uneven, criteria.

According to news reports, even this process is not functional. There is pressure from different ministries and agencies to include hundreds of unapproved and unfunded projects hoping to be approved and funded. For instance, in FY2021, in addition to the 1,584 approved ongoing projects, the initial ADP included a total of 1443 unapproved projects without fund allocation and feasibility studies.

The ADP contains several projects that make no progress during the year as they have no funds. An earlier review found 66 projects had been allocated less than Tk 10 million or one crore. It suggested that the inclusion of new projects and thinning of funds were slowing the implementation of projects. As a result, on average, projects were taking longer than six years to be completed.

Projects are not required to identify future recurrent costs requirement in their project documents. Thus, there is no guarantee that the operations and maintenance of these projects will be funded after completion. That is what happened to the deep tube well in Jobra.

The weakness in rigorously vetting projects is most dramatically illustrated by the high electricity production costs in Bangladesh, partly due to Purchasing Power Agreements. Some private producers are paid fees for installed power capacity. Thus, although installed generation capacity has an excess capacity of nearly 10,000 Megawatts, press reports say that government is paying Tk 50.0 billion to a few private producers every year as payment for these fees. Further, projects that will generate more than another 10,000 Megawatts are currently under construction despite the current extra capacity. That throws into question the financial viability of all existing power generators – whose purchase has not been guaranteed.

BUDGET SPACE FOR HIGH PRIORITY EXPENDITURES AND PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION : We will conclude by making two points. The first is aspirational and perhaps provocative, but not fanciful one hopes. Altogether we have suggested that Tk. 1.12 trillion of high-priority expenditures deserve financing beyond what has been identified in the Budget. These will be for vaccines, supplementary health care budget, funding for relief during lockdowns in the next year, and markedly boosting expenditures on repair and maintenance. How can these be financed? The prudent path will be to reallocate funds instead of taking recourse to additional borrowing. The sources for reallocation can be from the following: Ministry of Finance’s extraordinary reserve budget (Tk. 700.0 billion.), Other Subsidies (worth Tk. 192.89 billion that are not production or export subsidies), the already budgeted Tk. 223.63 billion for Social Assistance and Disaster Relief. These three items fill the gap. It is quite likely that the government has already planned some of these reallocations. But there may be constraints to using some of these funds. So, an additional option to consider is to make a significant effort to prioritise the Annual Development Programme and release 1.0 per cent of GDP (Tk. 346.0 billion) out of the ADP to support the unique needs for this year.

In closing, the government should consider using some of this reallocated money to increase Economic Management capacity. To that end, consider dramatically increasing the budgets for Planning (now budgeted as Tk. 11.33 billion), Statistics and Informatics (Tk. 16.73 billion), and Implementation Monitoring and Evaluation (Tk. 2.57 billion) and providing the latter two organisation with greater independence and public accountability. Think about this: the Bangladesh government spends one-tenth of 1.0 per cent of its Annual Development Programme to monitor and evaluate its implementation. On collecting statistics on Bangladeshi’s national economy and livelihoods, it spends one-twentieth of 1.0 per cent of GDP. With these kinds of funding for critical data, our policymakers are trying to fly a Boeing 777 with an old Cessna plane’s instrument panel.

Dr. Ahmad Ahsan is Director, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh. He was previously a faculty member of the Economics Department, Dhaka University and a World Bank economist. ahmad.ahsan@caa.columbia.edu.