Over the last three years, I have been systematically writing a review

of the annual national budget once announced by the honorable finance minister. These analyses are in the public domain, published by The Daily Star and the Financial Express. If one cares to review those write ups, it will become obvious that the main messages of each piece are remarkably similar.

While revenue performance has slowly improved over time and each budget by and large has preserved macroeconomic stability by keeping budget deficits low, the long-term structural weaknesses of the budget in terms of ability to reduce poverty and increase GDP growth remain unaddressed.

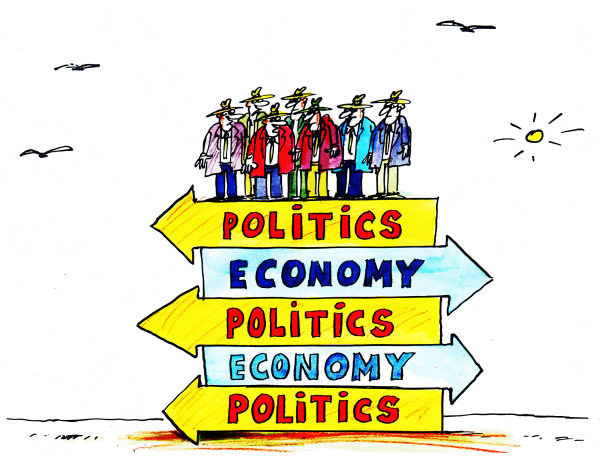

Indeed, this message is relevant for the entire period since independence. So, instead of writing yet another review of the recently announced FY14 budget, I am venturing to take a broader and longer-term perspective of the national budget from the point of view of political economy.

I will argue that the main reason why the long-term structural weaknesses of the budget stays even after so many years since independence is primarily because of political constraints and poor governance that remains an unfortunate hallmark of policymaking in Bangladesh irrespective of which government is in power. Breaking away from this stranglehold will require fresh thinking, new perspective and a social contract by the government of the day with the citizens.

It would be fair to think of the decades of the 1970s and the 1980s as the formative years of nation-building and learning the art of self-governance. With the advent of democratic governance since the early 1990s, the accountability of the government to its citizens takes on a new meaning.

The national budget is one of the most important manifestation of good governance and institutional strength of the country. The budget empowers the government to take away resources from the people and spend them. This authority, if used wisely, could have substantial long-term benefits for the citizens.

If not used wisely, this could have serious long-term negative effects. In the case of Bangladesh, the score card suggests a mixed performance.

The table shows the long-term progress with the structural reforms of the budget over the past 20 years measured in terms of a number of indicators. The record is mixed. On the positive side Bangladesh has done well in keeping fiscal deficits and public debt under control (fiscal deficit as a share of GDP at or below 5 percent and debt/GDP ratio below 50 percent and declining), keeping the size of government wage bill manageable (at around 3 percent of GDP).

Some success has also been achieved in increasing the tax to GDP ratio (from 7.3 percent some 20 years ago to 11.2 percent now).

On the negative side, despite progress, the tax to GDP ratio remains low by international standards and in relation to development needs (11 percent of GDP); the subsidy bill has increased at an alarming pace, rising to 3.6 percent of GDP; at only 3.7 percent of GDP the human development spending (health, education, family planning, nutrition and water supply) is much lower than needed; spending on social protection is limited (2.2 percent of GDP); and public development spending is low (only 5 percent of GDP) and has not improved over the past 20 years.

On the surface, the FY14 budget would appear to be making a mild effort to break from the past by cutting subsidies and increasing development spending. But once we allow for expected shortfalls in the implementation of the tax collection effort, the development budget and the subsidy bill the likely outcome is consistent with the long-term pattern. Additionally, the expected jump in the government’s wage bill appears like a pre-election measure and can present some difficulties for managing the budget deficit.

What are the development implications of the observed long-term budgetary trends: low human development spending; low spending on social protection; low total development spending; high subsidy bill; and low tax/GDP ratio?

In relation to its income level, Bangladesh has made very good progress in improving human development by focusing its limited spending on expansion of primary and secondary education and on low-cost programmes for the prevention and control mass communicable diseases (diarrhea, malaria and polio). This is a laudable achievement.

Yet, the second-generation challenges in education and health relate to improvements in the quality of education, the expansion of tertiary education, the development of skills, and the expansion of curative health care to the population.

Low spending on human resources seriously constrains the ability of the government to handle these challenges. The poor are most affected because the rich have access to private providers. In education, the growing quality gap between private and public provisions is a serious challenge to equality of opportunities and would appear to be a major contributor to the yawning income inequality in Bangladesh.

Low spending on social protection is also a major concern. Despite various commitments, including in the sixth plan, the government has been unable to raise the social protection spending beyond the 2 percent of GDP level owing to resource constraint. While there is scope for improving the effectiveness of current spending and efforts are underway to develop a comprehensive national social protection strategy, the narrow fiscal space is a serious constraint to financing a growing need for safety net programmes to protect the poor and the vulnerable.

Of most immediate concern is the slack in the public investment effort. The 5 percent of GDP spending is much below what is needed to invest in infrastructure, agriculture and human development. This is also substantially below the level projected in the sixth plan.

In addition to implementation problems, including serious governance concerns relating to public procurement (Padma bridge debacle is a good example), the narrow fiscal space is a major constraint to the expansion of public investment.

The expected financing of infrastructure from public-private-partnership (PPP) did not take off substantially owing to weak institutional and legal framework.

While important areas of public spending suffered from a resource constraint the subsidy bill expanded substantially. Much of the subsidy relates to energy and fertiliser and to a limited extent on food grain procurement. The growing subsidy bill has further complicated budgetary management.

On the tax front, in addition to the low tax effort that has constrained the fiscal space, there are serious concerns about the efficiency of the tax system. For example, continued strong reliance on international trade taxes constrains the diversification of exports; the much higher reliance on indirect taxes reduces the efficiency of resource allocation; and the combination of high corporate income taxes along with huge exemptions in taxes on capital gains and property taxes biases the incentives in favor of investments in land holdings and stocks as opposed to investments in manufacturing.

On the surface the policy options for a better budgetary management are clear: improve fiscal space by raising the tax to GDP ratio; improve the tax structure by reducing reliance on trade taxes and increasing revenue collections from personal income and property taxes; cut energy subsidy by aligning prices to cost; increase allocation for human development, social protection and development spending by raising taxes and reducing energy subsidies; and improve public procurement by eliminating corruption in procurement.

Indeed I have fed these policy messages consistently in all my reviews of the annual budget over the past three years. The fact that these reforms are not implemented suggests that there are there are major political economy constraints with budget formulation and implementation that remain unaddressed over the past 20 years.

A tax to GDP ratio of 15-16 percent of GDP is an achievable target over the medium term and can go a long way in addressing the fiscal constraint. This can also be achieved by reducing the reliance on trade taxes.

Specifically, the revenue composition in terms of GDP could be: 7 percent from income taxes; 7 percent from domestic value-added taxes and 2 percent from trade taxes as opposed to 3.4 percent, 4.2 percent and 3.4 percent respectively at the present time.

The largest scope for revenue mobilisation is from personal income taxes. Presently, total income taxes are a mere 3.4 percent of GDP, of which personal income taxes account for only 1.7 percent of GDP.

According to the 2010 HIES, the top 10 percent of the population accounts for 35 percent of the national income. By implication, it is clear that the effective personal income tax rate is a mere 5 percent. Doubling this effective rate to 10 percent would increase personal income taxes to 3.5 percent of GDP. Bringing capital gains from property transactions and stocks in the normal tax net (with a presumably lower rate) and introducing a proper property tax will go a long way to improve tax collection from personal income and wealth. The corporate tax structure could also be improved by rationalising many of the exemptions, rethinking the taxation of the RMG sector profits by treating them similarly to other corporate sector, and ensuring that the high corporate rates do not serve as a disincentive for investment.

The biggest hurdle to tax reforms is the control of the rich and powerful in policy making. The top 10 percent of the income owners comprise of big business, the politicians, and the elite. Directly or indirectly they control decision making irrespective of the government in power. The exemptions of capital gains from land holdings and stocks and the lack of a functioning property tax system are the outcome of protection of self-interest by this group.

Similarly, the gains from trade protection accrue to domestic business houses who do not want to be exposed to international competition. Through the various business chambers they wield considerable influence on policy making.

Regarding public spending, the beneficiaries of energy subsidy are by and large the urban non-poor rather than the poverty level group whose consumption basket has a very low share of energy.

The urban non-poor have a much larger voice in policy making than the poor. Any effort by the finance ministry to curb energy subsidy has met with stiff resistance. On the other hand, the demand for higher budget for spending on human development and social protection comes mainly from the poor. This group is neither organised and nor do they have a major voice except through the 5 year national election cycle.

What is the way out? This is a difficult question to answer. One hopes and expects that the democratic process of national elections gets mature enough some day to bring in real competition in the political process and brings in leadership that is sensitive to the needs of its electorates. This is an evolutionary process that will also benefit from growing income and education. Other institutions such as the media and the think tanks can also help facilitate the process through public education and awareness campaigns.