If you think all the talk about an impending ‘fiscal cliff’ is a concern

of the American economy, think again. The world economy is far too inter-connected to be immune to emerging economic catastrophe within the shores of the USA. Even the expectations of a fiscal juggernaut in Washington have rattled stock markets (already battered by the Eurozone debt crisis) around the world since the re-election of President Obama. The fear is that if the politicians in Washington are unable to reach agreement, there will be serious ramifications for jobs and income not only in the United States, but also in Europe, the world’s emerging markets, and, by virtue of inter-connectedness, perhaps all the rest.

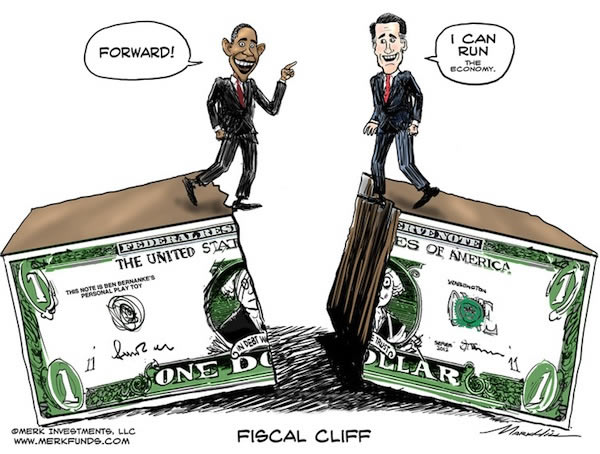

So what is this “fiscal cliff”, originating in Washington and causing so much anxiety across continents (see Box below)? Politically speaking, this was one of the major unfinished business of a Democrat President Obama’s first term resulting from sharp partisan positions over tax and spending policies in the US Congress, which has a majority of Republicans. While a bipartisan compromise was reached to raise the US debt ceiling to US$16 trillion and keep the economy going, the parties were too far apart in their stands on how to reduce the burgeoning fiscal deficit and mounting public debt over the long haul.

So what is this “fiscal cliff”, originating in Washington and causing so much anxiety across continents (see Box below)? Politically speaking, this was one of the major unfinished business of a Democrat President Obama’s first term resulting from sharp partisan positions over tax and spending policies in the US Congress, which has a majority of Republicans. While a bipartisan compromise was reached to raise the US debt ceiling to US$16 trillion and keep the economy going, the parties were too far apart in their stands on how to reduce the burgeoning fiscal deficit and mounting public debt over the long haul.

As a result, it was found convenient to kick the can down the road at least till after the US Presidential elections in the hope that voters will give a mandate to one party or the other to take the drastic actions each party espoused. However, as we all know, while President Obama got reelected, there is no evidence of a clear mandate from the voters one way or the other, except to put pressure on politicians to act. So the political gridlock over tax and spending continues leaving a lame duck Congress and a second term President to come to grips with the problem which must be resolved before 31 December, 2012…or else.

According to the independent Congressional Budget Office (CBO), in the event of failure to reach bipartisan agreement on specifics of reducing the federal budget deficit and public debt (what is now euphemistically described as ‘fiscal consolidation’), there will be automatic and momentous tax increases and spending cuts that are due to take effect at the end of 2012 and early 2013, as some tax and spending related legislations expire. In total, the measures are set to automatically slash the federal budget deficit by some $700 billion or approximately 4.0 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) between FY 2012 and FY 2013. In consequence, CBO predicts GDP contraction of 4.0 and unemployment rate rising to 9.1%.

What is politically most unpalatable is the eventuality that nearly 100 million citizens will suddenly find their salaries cut by higher taxes. Add to this fiscal conundrum the prospect of the debt ceiling of US$16.394 trillion being reached by end February 2013, followed by a protracted and rancorous debate in Congress. Whether partisan brinkmanship will finally give way to sagacious statesmanship in Washington is yet to be seen. And that contributes to huge uncertainty amongst investors and markets around the globe. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which has already made a downward revision of its outlook for the world economy in 2013, notes in its October 2012 report that massive fiscal tightening in the United States in early 2013 (if economy actually slips over the fiscal cliff) “is a primary risk to global economic stability”, adding that protracted gridlock in Washington would stall the U.S. recovery “with significant spillovers to the rest of the world”. In addition, “delays in raising the federal debt ceiling could increase risks of financial market disruptions and a loss in consumer and business confidence.

“While the thought of a US economy actually falling off the ‘fiscal cliff’ is unsettling to world markets, the challenge before lawmakers in Washington is not an easy one as they must grapple with a host of draconian tax and spending measures whose economic impacts are less clear when it comes to sustaining if not accelerating the feeble recovery the US economy is currently going through. If economic theory is any guide, neither spending cuts nor tax increases – two basic measures for reducing the budget deficit and, consequently, eventual public debt – will boost recovery as the economy slowly claws itself out of a deep recession. Nobel Laureate economist Paul Krugman has repeatedly said such a measure of fiscal austerity would be just the wrong medicine arguing instead for more spending and higher deficits to stimulate recovery and growth.

To be sure, events in the Eurozone are raising serious questions about the futility of austerity measures in times of weak economic performance. Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – much to the chagrin of the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schauble — has lately moderated its stance on what the speed of deficit and debt reduction should be, thus allowing more time and space to beleaguered economies such as Greece, Spain and Portugal. The experience of fiscal austerity in Europe has been anything but pleasant at a time when in some countries as much as a quarter of the labour force is unemployed.

There is the other unorthodox proposition of growing the economy via incentives to invest by cutting both public spending and taxes; but this idea has found few takers except among hard-line conservatives in the USA. The problem with this line of argument is that if incentives don’t bite and the economy fails to grow, it might be left with a bigger fiscal deficit and debt burden than it started off with. That sort of double whammy few political leaders anywhere can risk playing with.

So, what is at stake for Bangladesh? Let us first recognize that we live in a deeply inter-connected world from which we stand to gain when the going is good and suffer economic hardships when times are bad. Yet, isolationism is no answer. Developments in the US economy will have repercussions around the world, and Bangladesh, being a growing part of the inter-connected global economy, can hardly escape the loss of export demand that might ensue if there is no quick bipartisan deal in Washington. So jobs and income are at stake here at home for what happens in the distant US capital. Finally, what is my take on how the situation is most likely to unfold in Washington? I think US voters (confirmed by various polls) have sent a clear message to Washington that they would like to see an end to partisan bickering over the fiscal measures needed to put the economy back on track for higher growth and job creation. Both House Speaker John Boehner and President Obama wasted no time after elections to show some flexibility in their positions and their keen interest in averting an economic crisis not just for the USA but for the world economy. The best scenario is they will come up with the requisite statesmanship needed to resolve the crisis. The worst scenario is that they might have to kick the can down the road again by some legislative brinkmanship that will not appease world markets.