The budget comes in the wake of macroeconomic challenges stemming from rising pressures on internal and external balances in the past year. Years of generally prudent macroeconomic management have laid a solid foundation for macroeconomic stability that is a vital precondition for rapid growth. It is also important to safeguard the strong macroeconomic fundamentals that have been built, by not deviating from sound macroeconomic principles.

Therefore, the greatest challenge in budget implementation lies in making sure that there is optimal degree of fiscal and monetary policy coordination to keep inflation under control, exchange rate stable, ease pressures on the balance of payments, and yet leave enough space for private sector to invest and fuel growth. Ensuring macroeconomic stability in the face of these challenges requires mobilising adequate domestic resources to finance public expenditures on infrastructure, health and education, and therefore the government has put a lot of focus on raising revenue through tax and non-tax measures.

Though a gradual shift is taking place from reliance on trade taxes to domestic taxes, customs revenue still account for some 40 per cent of tax revenue. A number of proposals to adjust tariffs and para-tariffs have been made in the budget. A single message of trade policy that stands out in the budget statement is that the changes are done to assist local industries. Indeed, that might be so, at least for the time being. But just as a pampered child often becomes unfit to face the real world, industries propped up by high protection for too long are likely to face eventual decline as greater global competition is unleashed in coming years.

Like before, there is no announcement regarding how long such industry assistance through protective tariffs will continue. And the measures tend to be ad hoc in nature, without any background research about how much protection is justified, and for how long. Also, since protection is not uniform, we find no rationale for the variable rates of protection given to different products. So, while the benefits of protection are inequitable, it is consumers who end up paying the protection tax, indefinitely. This can hardly be justified under any policy principle.

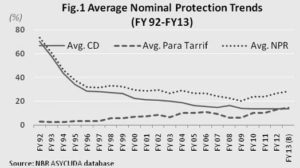

Before we proceed to discuss the implications of tariff changes in Budget FY2013, a snapshot of tariff trends over the last two decades may be gleaned from Fig.1. What is evident is the gradual decline of average tariffs until about FY09, following which there is an uptick that continues to the current budget. Though average CD has been on the decline, para-tariffs have emerged as a rising component to push up average NPR.

Nevertheless, a quick review of the increase and decrease of customs duty (CD) and supplementary duty (SD) rates is likely to lead one to believe that the predominant objective this time perhaps was higher revenue mobilisation than protection, though the latter outcome is consequential and, by and large, welcomed by the import substituting producers. In a few cases (43 tariff lines), CD on intermediate goods and basic raw materials were reduced. For a large number of tariff lines (413), SD was raised.

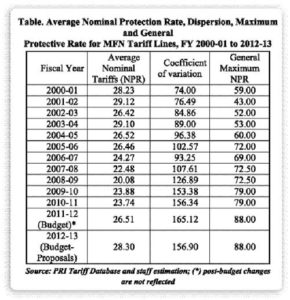

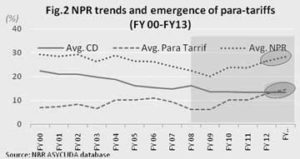

Assessment of tariff adjustments can be summarised as follows:l Upward trend of average tariffs for the past three years is maintained.l Tariff spread is also rising as evidenced from increase in coefficient of variationl General maximum NPR has also been rising; excluding rates on cars, alcoholic beverages, and tobacco, there are still about 500.tariff lines with NPR exceeding 100 per cent. Para-tariffs take the lead: Para-tariffs – import taxes and levies other than custom duties – have slowly emerged as a dominant set of trade taxes since the middle of the past decade. Supplementary duty (SD) and regulatory duty (RD) seems to have become standard instruments for raising revenue or offering protection to domestic import substituting industries, so much so that in FY2013, its share in average NPR has, for the first time, exceeded that of CD (52 per cent of 28.3, Fig.2).

Though SD was introduced in 1991 under the VAT Act, and was meant to be a trade-neutral tax. Like the VAT, increasingly, it has come to be applied in a non-neutral fashion, i.e. it is not applied equally on imports as well as domestic sales. Indeed, it has become an expedient instrument of protection through its differential application (higher rates on imports; lower or zero rates applied to import substitutes). Likewise, RD is now seen to be used on an ad hoc basis every year, only on imports, aimed primarily to raise protection to domestic industries, though NBR hopes it will generate extra revenue. The fact that there is hardly any objection from the producer community against these applications testifies to their favorable impact on protection. So far, such rampant use of para-tariffs seems to have escaped attention of WTO Trade Policy Review, since cross-country tariff comparisons available in UNCTAD’s COMTRADE database do not have information on para-tariffs. However, information on para-tariffs are being compiled and would soon become an irritant in multilateral trade discussions.

Tariff escalation without end: One of the key features of tariff reform was the move towards uniformity. Thus from 20 odd CD tariff slabs, the tariff structure is now characterised by four non-zero slabs of 3,5,12, and 25. The system presents low tariffs of 3.0-5.0 per cent for basic raw materials and capital goods, 12 per cent for intermediate goods, and the top rate of 25 per cent for final goods. However, on top of the 25 per cent for final goods, for a large group of products that are produced domestically, SD and RD are generously applied. Thus tariff escalation is the highest at the last stage of processing – from intermediate goods to final goods.

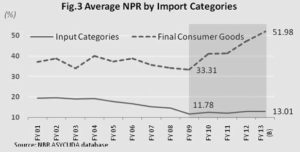

What is notable is that, since FY09, the wedge between the average NPR on inputs and final consumer goods is rising (Fig.3), thus augmenting effecting rates of protection. It appears to be the outcome of pre-budget consultations with producer groups only, without anyone speaking for the consumers who will eventually pay the protection tax (higher price) and also suffer welfare losses from lack of choice. In the short-term, enterprise profits may be propped up, but, over the long run, this trend is likely to have adverse consequences on productivity and competitiveness of firms that enjoy protection without an end period in sight.

Trade policy losing direction: A substantial portion of trade policy for FY2013 has been formulated under this budget, thanks to the proposals regarding adjustment of trade taxes. These adjustments affect profitability of import substitute production on the one hand and export competitiveness on the other with serious implications for trade as well as growth prospects. The budget essentially perpetuates the previous tariff stance with the singular statement of support to domestic (import substituting) industries. Is it sound policy in light of global competitive challenges and Bangladesh’s goal of attaining higher growth and reaching middle income status by 2021?

As it is, tariff protection levels in Bangladesh have been described by analysts as high. As mentioned earlier, Bangladesh regularly is being listed by multilateral observers as having a relatively restrictive trade regime.Continuation of this stance might prop up current profitability of import substituting firms. But import-substitute production catering to the domestic market cannot create jobs for the two million people added to the workforce each year. Export production can.

Research based on history and global experience indicates that such protection for long periods is bound to create inefficiency and undermine export competitiveness in global markets. We need to reflect if this is the kind of trade regime that will yield the 7.0-8.0 per cent GDP (gross domestic product) growth rate in the medium-term, and 8.0-10 per cent growth rate over the long-term, as envisaged in the Sixth Five Year Plan (2011-15) and the Perspective Plan (2010-21). International evidence shows that hitherto developing countries that grew at 7.0-8.0 per cent rate for a decade were completely transformed from low-income to middle income countries; but their growth record was characterised by open trade regimes — not the kind of trade regime we are pursuing.

Research based on history and global experience indicates that such protection for long periods is bound to create inefficiency and undermine export competitiveness in global markets. We need to reflect if this is the kind of trade regime that will yield the 7.0-8.0 per cent GDP (gross domestic product) growth rate in the medium-term, and 8.0-10 per cent growth rate over the long-term, as envisaged in the Sixth Five Year Plan (2011-15) and the Perspective Plan (2010-21). International evidence shows that hitherto developing countries that grew at 7.0-8.0 per cent rate for a decade were completely transformed from low-income to middle income countries; but their growth record was characterised by open trade regimes — not the kind of trade regime we are pursuing.

The Sixth Five Year Plan (SFYP) articulates a strategy for diversifying exports and developing a dynamic manufacturing sector. It states, “the structure of incentives created by the trade policy regime still favors the production of domestic import substitutes and creates barriers for emergence of new export industries and expansion of export industries not benefitting from special measures”. The SFYP then proposes removal of the remaining anti-export bias to create a neutral policy regime between import substitution and export promotion in order to focus both on manufactures that have export potential and industries which already export but whose potentials are not fully realised. It appears that these propositions have not been taken on board in formulating the FY2013 budget.

Summary of the key findings:

* Trade liberalisation is stalled; but no clear direction has emerged since the dawn of the new century.

* Although the RMG sector is free from the shackles of high tariffs on inputs or outputs, other exports or potential exports are not.

* The structure of incentives underlying the trade regime favors production of domestic import substitutes over exports, creating an inherent anti-export bias.

* Tariff and para-tariff proposals in FY2013 budget signals continuation of the recent trend of rising average nominal protection and wider dispersion of the tariff structure.

* While para-tariffs have been emerging as significant component of nominal tariffs, for the first time, its share has exceeded average custom duty.

* While nominal tariffs on inputs (basic raw materials and intermediate goods) continue to fall, those on final consumer goods trend upwards, thus widening the wedge between average tariffs on outputs and inputs, augmenting tariff escalation at the last stage of processing.

* FY2013 budget proposals on trade policy do not appear to be inconformity with the articulation of the kind of trade policy needed to improve export performance and support the high growth needed to reach middle income status by 2021.

Policy Recommendations:

* Trade policy orientation needs to change in order to support high growth.

* Trade liberalisation needs to be put back on track. For that, average nominal tariffs and their dispersion both have to be reduced.

* The wedge between input and output tariffs is wide, and getting wider. The highest difference lies between tariff on intermediates (12 per cent) and tariff on final goods (25 per cent+RD+SD). Such tariff escalation breeds inefficiency and undermines competitiveness of firms in the long run.

* It is high time for the top tariff rate, along with para-tariffs, to be scaled down, to give domestic consumers some relief.

* In framing trade policy, policymakers must balance interests of producers and consumers – the latter group is not organised like the former.

Dr Zaidi Sattar is chairman, Policy Research Institute, Bangladesh. This write-up was presented at a recent discussion meeting, organised by PRI, Bangladesh as a key-note paper. pri.bangladesh@gmail.com